War History Online presents this article from AARP The Magazine

“We honor the men and women who served, those who still serve today, and the friendships they forged in war”.

As told to William W. Horne, Christina Ianzito, Mike Tharp, Garrett M. Graff, Julia Lobaco and Garrett Schaffel.

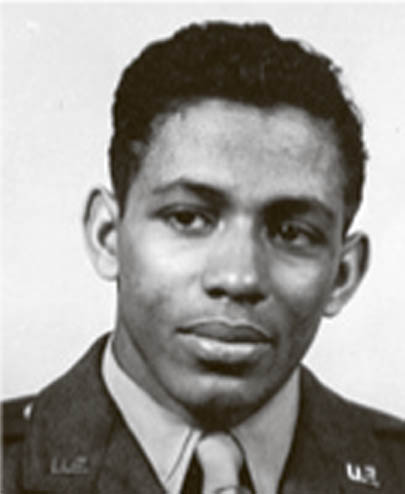

Lieutenant George Iles

By Lieutenant Harold Brown

Harold Brown and his buddy George Iles were two of the nearly 1,000 African American pilots, known as Tuskegee Airmen, in the segregated military of the 1940s. Both men flew in the 99th Fighter Squadron of the U.S. Army Air Corps in Europe.

I was on a strafing mission in Germany in March when a locomotive I was shooting at exploded beneath me and I had to bail out. Soon after, I got picked up by the Germans – which was a good thing, since the civilians were ready to beat the enemy to death -and taken to a POW camp near Nuremberg. Whenever they brought new guys in, all of the old inmates would hang on the fence looking for someone from their squadron. Well, that was quite a thing when I saw my buddy George hanging there – almost indescribable. Up till then, I’d been alone, and frightened since the civilians were ready to rip me to pieces. The chances were about one in umpteen million.

We’d flown together. Trained together. Went overseas together. Now, we were POWs together.

And we ended up being the only black guys in our compound. I joke that the first time I was integrated in the military was when I was a POW.

After just 10 days, the Germans marched us and 10,000 other POWs to another camp north of Munich because the Americans were getting close. It took us almost two weeks to get there, walking in groups of 200, sleeping under the stars. We were always hungry. The Germans didn’t even have enough food for themselves. Once a day they’d bring in a big pot supposed to be soup, which was really nothing more than water. George and I did what we could: once we cooked up dandelion greens. And instead of opening up two tins of Spam, we would open up one tin and share it to make our food last that much longer.

We were in the new prison for about two weeks when we started hearing the tanks rumbling. We knew it wouldn’t be long. Then on April 29, 1945, General George S. Patton came through with his tanks, knocked down the fences and liberated us. Iles and I and everybody else were hollering and screaming, so happy, happy! The war was over for us!

Back home we were stationed together for a while, then eventually led our separate lives. But I’ve always considered him a big brother. We couldn’t have been closer.

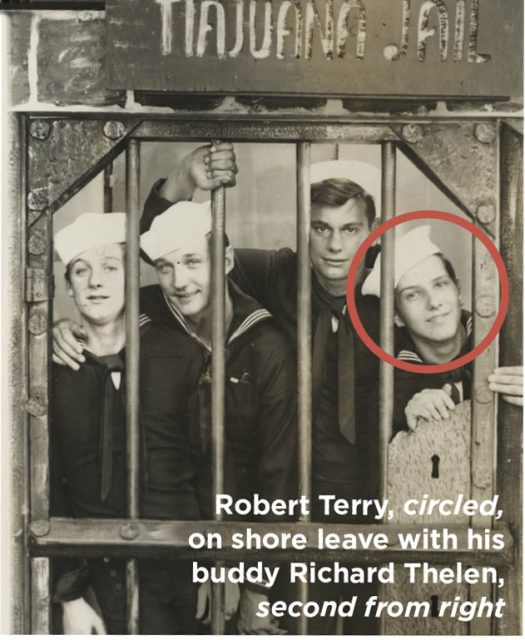

Seaman Robert Terry

By Seaman Richard Thelen

Richard Thelen was a sailor with his friend Robert Terry on the USS Indianapolis, shown below, when it was torpedoed in the Philippine Sea by a Japanese submarine and sank. Of 1,196 crewmen, about 300 died immediately. Of the almost 900 who survived the sinking, nearly 600 died over the next four days, from dehydration, drowning, and shark attacks; rescue operations were mounted too late to save most of the men.

Bob Terry was next to me at our first roll call in Navy boot camp in 1945. He was T-E, for Terry; I was T-H. We were both 18, and we both came from the Midwest. Then we got assigned to the Indianapolis together. We played cards and ate and went drinking together; we became real close friends. And we promised each other that if one of us didn’t make it, the other would go and talk to the family. When the first torpedo hit after midnight, I was sleeping topside – it was too hot below deck. The explosion threw me into the air. Luckily, I was flung onto a cable, or I would have been thrown into the water without a life jacket. The ship was listing heavily, and the quarterdeck was on fire. There was a lot of shouting and explosions. Then the ship just slid away beneath us. It was dark and suddenly quiet, though you could hear men shouting as we looked for rafts or lifeboats.

I was floating around in a kapok life jacket for the next four days – no food, no water, a hundred degrees out. There weren’t enough rafts. Then on the second day, Terry saw me. I don’t know how he recognized me – like a lot of guys, I was all covered in black diesel fuel, with my hair all matted down. I was glad to see him. We tried to hook our vests together so we wouldn’t float away, but it didn’t work because the swells just ripped the vests apart.

So we tried to keep floating near one another, Terry and me and two other guys. They were long days: You pass out, then come to, then pass out again. We were slowly dying. Waking up less, the sun beating down – still no food or water. I felt sharks bump against me, and once or twice I was looking right at one, maybe 16 inches away. But the diesel fuel masked me – I don’t think they cared for the smell.

On the fourth day, we spotted a raft – planes had dropped a few – and we decided to try to swim to it. Two of the guys died from the effort – in our condition, their hearts gave out, I think. Then Terry started to swim toward it. And while I watched, I saw a shark take him, just 20 or 30 feet away. I was three-quarters out of my head, so close to death – my mind was coming and going. But I thought, “it’s over.”

Later, I somehow made it to that raft, and there were four guys in it. I was too weak to pull myself in, so I tied myself to it. That night we were rescued, a little after midnight. They said that nearly all of the survivors were the ones who were in vests and stayed mostly submerged.

Six months after I got out of the hospital I went to see Terry’s mother and told her our story.

I’m a lucky guy, but I think about Terry all the time, even 73 years later.

Thelen, 91, became a long-haul trucker after the war. A resident of Lansing, Michigan, he is a proud father of six and grandfather of 17.

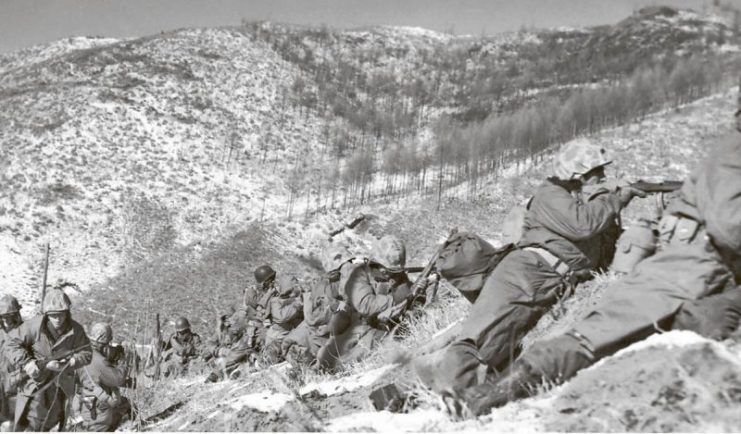

Sergeant Jack Deloach – Korean war, 1950

By Lieutenant Richard Carey

Lieutenant Richard Carey was in the 1st Marine Division at the Chosin Reservoir when an estimated 80,000 Communist troops surrounded U.S. forces in late 1950. One snowy night, Carey encountered his friend Jack Deloach, whom he’d met in 1949 when Deloach was a platoon sergeant at Camp Pendleton, in California.

I was in charge of intelligence in my sector and was told to get together a group of about 100 Marines and go up the hill to reinforce a company under attack. That’s when I ran into Jack, dug in on a hill. He was a good ol’ country boy from Georgia. Pretty rough language, colorful guy, with that southern slang. He wasn’t afraid to tell anybody what he thought. He loved the Corps and could do any job. He’d taken shrapnel in his forehead, a grazing wound that was bleeding badly, and he couldn’t see very well. “Sarge,” I said, “I’m here to help as much as I can,” and he said, “You’re welcome to join in, Lieutenant, we could use you.” So I crawled into the foxhole with him.

He was peeling grenades out of a container and handing them to me, and I was pulling the pins, letting the spoons fly. I counted, “One thousand one, one thousand two”—they were three-second grenades—then I tossed them. The Chinese were right on top of us. We had a helluva fight but held the hill.

It helped that we had called in Corsairs with napalm. I remember watching those planes with Jack, thankful but also jealous. I said to him, “Those pilots are going back to Japan to a warm bed and a hot meal. I’m going to put in for flight training.”

In March 1951, I was wounded – they awarded me a Silver Star after that battle – and I spent a couple of months in the hospital. The next year I went to Pensacola, Florida, for flight training. And there, sure enough, was Jack, training officer candidates. I greeted him by saying, “There’s the old soldier doing everything he can for our Marine Corps!” Jack just grinned and said,

“I’m honored to do it, Captain.”

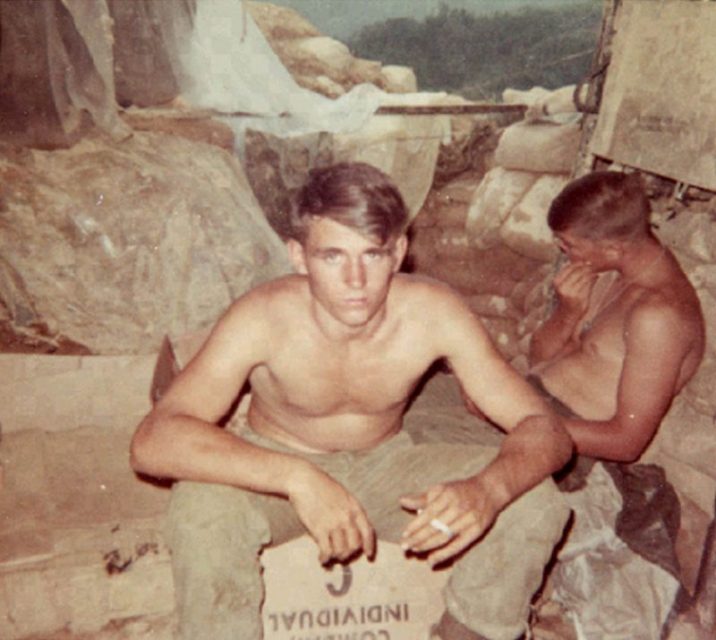

Ramo – Vietnam War, 1970-71

By Specialist 4 Jim Brim

Jim Brim landed in Vietnam in July 1970 and became the handler for Ramo, a German shepherd, when he joined a scout-dog platoon assigned to the U.S. Army’s 25th Infantry Division.

The sergeant told me I was lucky to have Ramo because he was so good at what he did. He was a scout dog; his assignment was to detect ambushes and find booby traps. You’d work for seven days, then come back in. That was the longest a dog could stay out. You’d carry his food and canteens for him, as well as your own gear, such as an M16 rifle, mags of ammo, hand grenades, a blanket and my food. We’d get on a helicopter to fly to an infantry unit, and they’d drop us off.

I got attached to Ramo. Sometimes he slept in the hooch with me. He was always next to me: standing, sitting or lying down. We had an unspoken bond. And we had some close calls – came under mortar and small arms fire – but Ramo stayed right with me.

When their tour was up, our dogs would be euthanized or handed over to the South Vietnamese Army. But in 1971, the U.S. decided to send dogs back to Lackland Air Force Base, San Antonio. Ramo was one of the first to leave. It was tough to see him go, but I was glad he wasn’t left in Vietnam. I never saw him again. I hope he filled out his days in a cool, shady place.

Brim, 70, became a financial planner and investment adviser in Bartlesville, Oklahoma.

Corporal Charles Thomas – Vietnam War, 1968-69

By Lieutenant Karl Marlantes

Karl Marlantes was 23 when he went to Vietnam as a Marine Corps officer.

Charles Thomas was a grizzled 18-year-old who had been there seven months when I arrived. He was my radioman, and he helped me out, always dropping hints. It would be, like, “Well, I don’t know, Lieutenant. I would think about that again.” Luckily, I listened. And you get close because radio guys are with you all the time. Then, in early December 1968, we were on a long mission, high in the mountains, and it was monsoon time. We couldn’t get resupplied and were without food for three or four days. It was also cold, but we had no extra clothes, just the stuff rotting on us. One night, I got hypothermic, really hypothermic. I couldn’t think and started shivering. Everybody knew hypothermia kills you. And Thomas just laid me on the ground and wrapped a quilted poncho liner around us and hugged me. And then his body heat got me back. Saved my life.

But then, since he was so talented, I made him a squad leader. In ’69 we were assaulting a hill, and I sent him with his squad around the back; I wanted him to set up an ambush. Because we were in a battle, I was shouting at him: “God damn it, Thomas, I want that machine gun there!” He rushed it, broke cover and the NVAs [North Vietnamese Army troops] on a ridge saw the squad and hit it with rocket-propelled grenades. Killed Thomas and another Marine.

I had to go through all the guys’ bodies to pull out, if you can believe this, anything like pictures of naked girls, so their parents wouldn’t be upset – it’s bad enough that their kid comes home in a body bag. And I pulled a letter out of Thomas’ pocket from his mother and remember it said, “Don’t you worry, Butch.” We knew each other only by last names and nicknames. I never knew he was Butch, that his mother called him that. “Don’t you worry, Butch, you’ll be home in just 11 more days.”

Marlantes, 73, the author of the memoir What It Is Like to Go to War and the novel Matterhorn, lives in Woodinville, Washington, and is at work on a new novel.

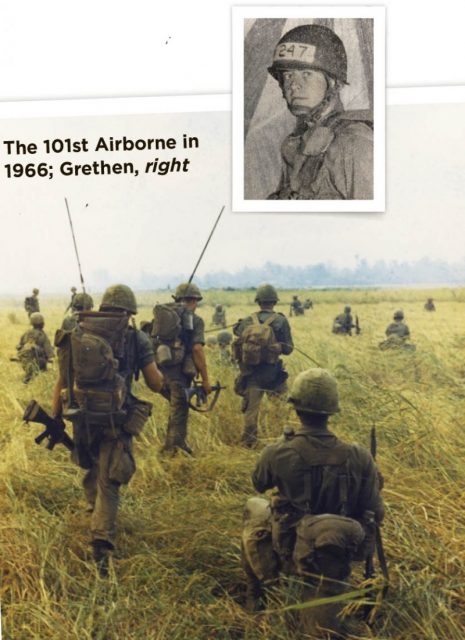

Private Galen Grethen – Vietnam War, 1966

By Specialist 4 José Andrés Girón

José Andrés Girón was one of the first combat airborne troops of the U.S. Army 101st Airborne Division to arrive in Vietnam, in July 1965. It was miserable. Every day we would go out on patrol or on a mission. We’d be wearing the same clothes day after day, going in and out of rivers, pulling leeches off our bodies and burning them with a cigarette. We were lost one time and had no cigarettes, food or water for about three days. I’d dream I was back in Phoenix enjoying a summer night, then wake up in that hell-hole. When they finally found us, they dropped some water and food. Those cans of lima beans that we hated, they tasted so good!

And every day we knew we may get killed today; we may get killed tomorrow. But if we could just make it this one year, we could be home, enjoying a hamburger and – oh, my God – 7 Up! We wanted to make it. But some of us didn’t.

I got shot nine months into my tour when we were hit in an ambush on a search-and-destroy mission in Tuy Hòa. It was deafening, the sound of fire. Bullets everywhere. Everybody was firing like crazy. I got hit in the leg. I yelled for help.

As I lay there bleeding, here comes Doc Galen Grethen, the medic. He seemed very young. He always wore black glasses on his little face, with a flattop, and was kind of uncoordinated. We played cards with him on our breaks – he came alive when we played,winning a couple of big pots.

So he heard me and, thankfully, here he comes. I’m looking at him and expecting him to low crawl; we’re trained to low crawl. But then he stood up! And was moving toward me, maybe 10 paces away down the trail. I was wondering what he was doing and his eyes met mine, then – boom! – and he went down. He was dead. Just dead. And as soon as I realized that, I thought, “My God, I’ve killed him, by yelling out to him.” But then, that’s his duty to come.

I didn’t have long to grieve. Suddenly here’s another medic! He came up like Audie Murphy, man. He had an M16 and was firing away and low crawling. He got to me, pulled me behind a tree and gave me a shot of morphine. That was the worst and happiest day of my life because I knew I was getting the hell out of there. The firing stopped, and they put me on a stretcher, carried me to the drop zone. I was going on that chopper. We got on, and the other wounded got on.

Then they pulled in the body bag with my buddy the medic. I could still picture that little face in that body bag. And I still see it every once in a while. I’ll have a dream, and I’ll see that face staring up at me with his little glasses. And it haunts me.

Sergeants Tommy Field and Bill Cleveland – Battle Of Mogadishu, Somalia, 1993

By Captain James Yacone

Army Captain James Yacone was a Black Hawk helicopter pilot and a platoon leader with the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment stationed in Mogadishu, Somalia, in 1993. On October 3 an operation he was involved in (and which was later memorialized in the movie Black Hawk Down) went horribly wrong.

On October 1, my birthday, I’d been deployed about three months, and our mission was to search for Mohamed Farrah Aidid’s top lieutenants. We didn’t have good intelligence, though, so the missions were few and far between. Just before dinner that day, the crew chiefs came into my office with duct tape and shaving cream. In the lead were Tommy Field and Bill Cleveland.

They had been very welcoming when I arrived – and you could count on them. Bill was not the neatest chief; he usually had a dirty uniform from working on the aircraft but was meticulous in how he did his job. Tommy was a bit quiet but was always the first to help anyone out. So they’re all laughing, and they duct-taped me to my chair and started to lather up my head, then took out their Spyderco knives. They didn’t shave me, in the end, but I’d passed: After they cleaned me up, Tommy and Bill presented me with a guidon – a military banner – that Tommy had made out of a burlap sack. He’d sewed it himself, put the company emblem in the middle, then had everyone in the company sign it. It was funny but also touching, and took on a whole new significance a couple days later.

We’d flown into Mogadishu with another helicopter, Super 61. When it was shot down, we helped direct the ground forces over to the crash site and provided air support. But I quickly realized we couldn’t respond to all the calls from troops for fire support and requested another aircraft. Mike Durant’s Black Hawk, Super 64, was available. That crew had already inserted troops and was holding north of the city. Bill and Tommy were the crew chiefs aboard, the door gunners. Mike joined me and orbited for just a few minutes before he was hit, too. He and Ray Frank, the co-pilot, maintained control and tried to make it back to the airfield. They got about a mile away when the tail rotor came apart and they crashed. The first convoys that attempted to reach them came under heavy fire and turned back. My aircraft was it. We moved over their crash site, and my crew and our three snipers in the back got into a firefight. Looking down, we could see that Mike and Ray were moving and that one of the crew chiefs was badly injured. I don’t know whether it was Tommy or Bill.

We finally inserted two of the snipers, Gary Gordon and Randy Shughart, about 150 yards away, and the plan was for them to move to the downed aircraft and carry the crew back to where we could extract them all. But a rocket-propelled grenade hit us just moments later before anyone could be extracted. When we got hit, I just remember feeling awful – and again helpless. I was concerned for our aircraft, sure, but my main thought was, Sh-t, there’s no hope for Super 64.

We made a controlled crash. I had minor shrapnel wounds. Our third sniper, Brad Halling, had lost his leg to the RPG. One crew chief had been shot through the arm; my other chief had a concussion. I got back to the airfield, swapped with another pilot and flew the rest of the night. But Bill and Tommy were dead, along with Randy and Gary, both of whom were awarded the Medal of Honor posthumously. Once our aircraft was shot down, the men at the Super 64 crash site were overrun, and everyone was killed in action except for Mike Durant, who was taken captive by the enemy for 11 days.

Today that guidon hangs in my living room, and whenever I look at it, I think about that day and those guys.

Captain James Yacone, 52, was awarded the Silver Star for his heroic attempts to save his comrades in Mogadishu. After leaving the Army, he spent 21 years in the FBI, including as an assistant director, before retiring in November 2015. He is now director of operations for SANS Institute, a cybersecurity company headquartered in Bethesda, Maryland.

Specialist 4 Aaron Sissel – Iraq War, 2003

By Specialist 4 Miyoko Hikiji

Miyoko Hikiji, then 26, and friend Aaron Sissel, 22, were both from Iowa and met while training at an Army and National Guard camp there after 9/11, first as gate guards, then as truck drivers. In May 2003, they were assigned to drive supplies in northwestern Iraq. In November, Sissel’s convoy was attacked on the road.

Aaron would do anything for a friend. We were helping supply materials to that part of Iraq, always crisscrossing around, meeting back at the base, then going back out for a day or a week. His girlfriend was at another base in Iraq, and my boyfriend at the time was usually on a mission at another base, too, so Aaron and I were each other’s mail person, delivering messages for each other when we could. Aaron would always take the time to ask, “Hey, got any mail for John?”

He was a super-hard worker, really likable, and he’d tell me about his girl, about how they were going to get married when they got home.

On the 29th of November, I was driving up one of the main supply routes, going north, and he was driving south toward the base on the same road. I was in the passenger seat, running the radio, and we started to hear there was an ambush. I heard the truck number, but we didn’t know who it was. When we got back on base, we saw a quick reaction force was waiting at the gate to go get them, and we heard the helicopters go out. My boyfriend was waiting there – he thought it was me. He was, like, “Oh, my God, I’m so glad it’s not you.” But that’s when we found out. Aaron had been shot and had bled to death.

I really regretted, when we heard about the attack on the radio, that the convoy had not gone north, beyond the base, to meet his, to see if there was anything we could do. Headquarters had told me no, that they had the quick reaction force ready to go out. They said there was probably nothing we could have done while Aaron’s convoy was still being shot at, but I wish I’d had the chance to try.

They brought his truck back with all the bullet holes in it. Nobody wanted to drive it; they thought it was bad luck. There were still bloodstains and skin in the truck. I said, “I’m going to drive that truck.” I felt like I needed to do that for Aaron – saddle up, you know?

I’ll just never forget him because he was really that person who comes to mind when people talk about the goodness of an American soldier, the person who never gives up, the person who works really hard.

Even before Aaron died, I think I knew absolutely every day when I left that gate that there was a chance this was going to be it. But the curse of living through that for that year became the greatest gift for me for the rest of my life. Because I’ve never, ever taken my life for granted.

Miyoko Hikiji, 41, is the author of All I Could Be: My Story as a Woman Warrior in Iraq. She was a candidate for the Iowa state Senate in 2016 and lives in Urbandale, Iowa, where she works as an employment services manager.