Civilization likes to lionize men who serve in war, clearly a centuries-old tribute. But 100 years ago in World War I, the world lost an entire generation of young men who have earned infinite tributes, chiefly because WWI was like no other.

With new machine guns, poison gases, trench warfare, and wafer-thin aeroplanes, it was a bewildering end of innocence in the battlefields of France.

La Belle Epoque in France had enjoyed peace and prosperity for nearly 50 years, but that came to a halt when World War I began. With the U.S. maintaining its isolationist policy, France was virtually on its knees. Yet some American men, who had learned what France was battling, individually volunteered to fight alongside their ally.

Hamilton and Wenham produced two remarkable young men, Samuel Mandell and Norman Prince, who made a difference in the methods of waging this war in Europe. Both rookie pilots, they flew some courageous air missions over France, and both lost their lives there—but not before making a historic impact on aviation.

Norman Prince was a wealthy Harvard graduate. He had been obsessed with the new flying machines since boyhood, and was capable of both flying and building one. Young Samuel Mandell, still a Harvard student, left Cambridge and entered the war flying in, most notably, De Havilland 4s, otherwise known as “flaming coffins.”

When Prince arrived in France in 1915, he managed to convince the French Aviation Service to allow him and his colleagues to form an all-American squadron of pilots. They went on to fly the skies over France, leveling German facilities below and engaging in aerial dogfights.

He once said, “Someday soon we will all be united in one escadrille—an Escadrille Americaine—that is my fondest ambition.”

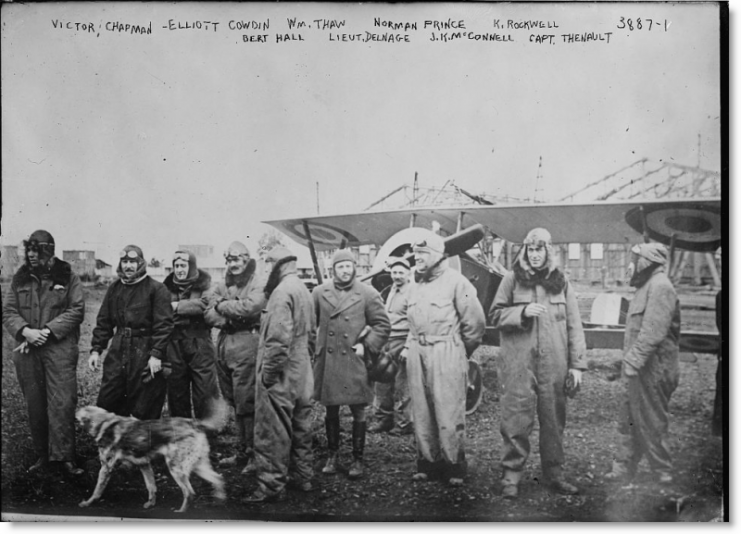

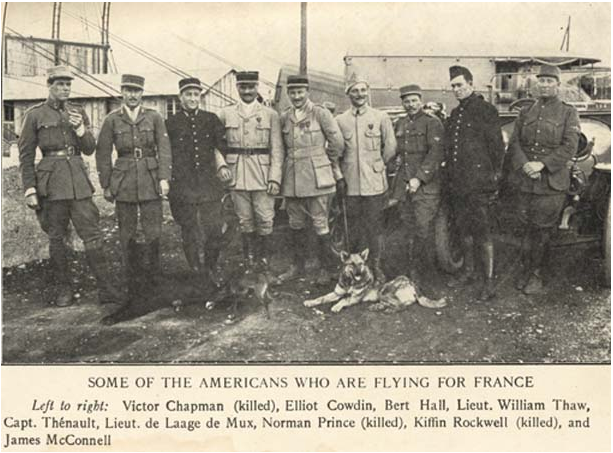

Originally dubbed Escadrille Americaine, it eventually became known as the celebrated Escadrille Lafayette. The pilots were a cast of characters: Ivy Leaguers, most from Eastern states, eleven millionaires, blue-collar workers, brick layers, farmers. Some had first joined the French Foreign Legion and later the Escadrille. One was blind in one eye, another deaf in one ear.

Their ages ranged from 20-40 and despite diverse backgrounds, their devotion to their fleet guided the war’s direction even before the U.S. was involved.

Norman Prince flew 122 missions with the Escadrille, and once described what his first bombing operation was like: “The terrible racket and the spectacle of shells exploding nearby made me shiver. My limbs began to tremble…My legs were so wobbly…that I tried to hide them from my observer [crew officer] who was an old hand at the game.”

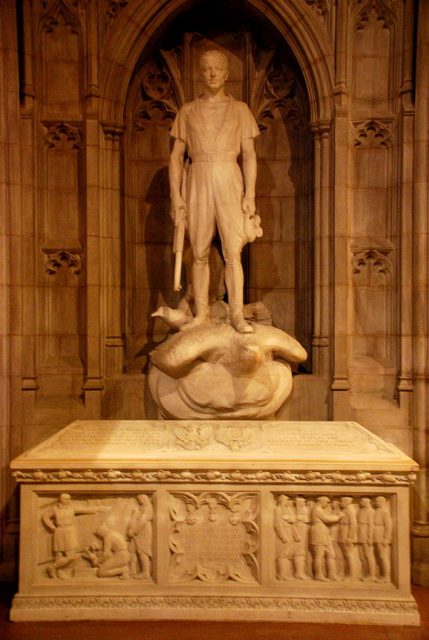

On Oct. 12, upon completing a vital mission, he returned to the airfield that night in Alsace. Just shy of the dark landing strip, the wheels of his Nieuport 11 biplane got tangled in a tall telegraph wire. His plane lurched and crashed, breaking both Prince’s legs and cracking his skull. He died three days later and was ultimately buried in a grand crypt in Washington D.C.’s National Cathedral.

Prince was 29 years old, and was awarded the Croix de Guerre, Médaille Militaire, the Croix de la Legion d’Honneur, and promoted to Sous-Lieutenant. There were other great men in the Escadrille Lafayette, but Prince is remembered for his pioneering and persuasive manner in founding the legendary squadron.

Though Lieutenant Samuel Mandell was not part of the Escadrille, he fought in more than 17 aerial assaults. Following a successful mission on Nov. 5–the final air raid of the war–he was shot down and was badly wounded. While he awaited first aid for both broken legs and other severe injuries, a nearby German took a rifle and fired several shots into the 21-year-old pilot.

He died just days before the Armistice was signed and is buried in Mt. Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge. The Community House in Hamilton was established by his parents in his memory. Mandell’s piloting achievements, skill and bravery are remembered as well as all his successful missions, especially the punishing Argonne-Meuse offensive he fought with the 20th Aero Squadron.

In a park outside Paris in Marnes-la-Coquette is a stately monument, the Lafayette Memorial. Erected in 1928, the arch is dedicated to the men of the Escadrille. Inscribed on the walls of the memorial is written:

“To keep alive in the hearts of men the spirit which inspired the members of the ‘Escadrille Lafayette,’ all Americans to volunteer for the universal cause of Liberty under the Flag of France, before their Country’s entrance into the Great War.”

On April 20, 2016—exactly 100 years to the day—of the establishment of the Lafayette Escadrille, a commemorative ceremony was held at the Lafayette Memorial and those original pilots were extolled for their sacrifice to France. And this year, on the very day the Armistice was signed 100 years ago, bells will ring across the country on the 11th day of the 11th month, at 11:00 a.m. in memory of the war to end all wars.

At 4:00 p.m. on Saturday Nov. 10, The Community House on Rte. 1-A in Hamilton, Massachusetts will host a celebration honoring the heroes of WWI, especially the Flying Aces of the Escadrille Lafayette and the young men from Hamilton-Wenham who lost their lives.

Read another story from us: When the Germans Attacked Massachusetts – The Battle of Orleans WWI

In addition to a theatrical presentation and exhibit of WWI memorabilia, visitors can enjoy a keepsake portfolio of local history, bios and photographs, discussions, and refreshments. Parking is free and the building is handicap-accessible. Information for this exceptional celebration can be found HERE.

Dorothy V. Malcolm is a freelance writer on history and the arts and author of “Legendary Locals of Salem.”