Often, my father frustratingly reflects on his 17-year stint in the office of a sugar beet factory through the realization that almost every man around him would have taken part in WWII. My mother tells of her headteacher having two wooden legs and a metal plate in his head. No one asked why – the interest just wasn’t there.

Born in 1917, my grandfather was an entire period of history away from my dad who, born in 1953 spent his teens and twenties growing his hair and thrashing Vespas down to the coast. Now, at 65, as so many other sons and daughters of the greatest generation do, he asks himself why? Why didn’t I ask?

As a child growing up in the Suffolk countryside in the 1990s, despite being half a century later, “the war” was still spoken about as if the passage of time had yet to begin the inevitable deterioration of both remains and memory. But then, why wouldn’t it be? The children that saw it all were just reaching middle age, and the veterans themselves were enjoying their first decade of retirement.

From the passenger seat of a Ford, I so often gazed out at the pillboxes that littered the place I called home and curiously asked what they were. “From the war”, spoken so unceremoniously that the reality of those concrete structures, dotted across the countryside in a last-ditch plan to halt the inevitable German invasion, was made almost trivial. The invasion, as we know, never happened – but how many people really reflect on the danger Britain was once in as they pass those haunting forms, loitering in gangs of three on the edge of rivers and roads?

I was in Dunkirk for the 75th anniversary of Operation Dynamo and was astonished to find bunkers of the Atlantic Wall being reused as art pieces. The most overbearing fortification had been covered entirely in a mosaic of mirrors, forcing the passerby to literally reflect on the history of the English Channel during the war. My mind returned to a memory of my childhood where I excitedly played on, in and around a pillbox that had half sunk into the beach of a seaside town. Returning as an adult, a new generation of children were enjoying the formidable structure. They were sure to ask their parents on the way home what it was they were playing on, and they will be told: “from the war.”

“The war”, thrown around in countryside conversation like it was nothing. Which war? Whose war? For school homework, we were to ask our grandparents about “the war”. The war was and is, definitively and stubbornly, the Second World War. Because it was this war which not only haunted a generation but scarred the landscape of the villages that so often come to define Britain. It is because of this, having traveled the world’s battlefields, that the history of Suffolk’s airfields holds a special place in my heart.

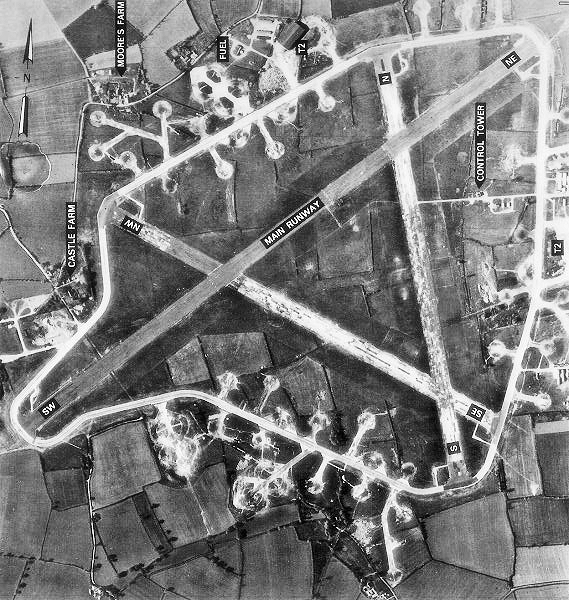

One mile from the house I was raised in sits the crumbling remains of Rougham Airfield, or as it was known between 1941-45, RAF Bury St. Edmunds. The airfield was the wartime home to the 94th Bomb Group of the 8th Airforce. It saw 329 missions leave the grounds to drop 18,995 tonnes of bombs on enemy targets. This inevitably saw the eventual loss of 157 aircraft and an estimated 1,835 men killed, injured or captured.

A huge moment in history not only for losses but the transformation of the area. Farms were flattened, thousands of trees cut down and private houses handed over to allow for the charmingly named “Friendly Invasion” of Americans into our tiny East Anglian village. But as is so often the case, the post-war years saw the airfield and all its astonishing achievements fall into forgotten memory. To most in the area without a personal interest in the wartime history, the airfield is more likely to ring a bell in the minds of people who attended the moderately infamous Albion Fayres and Peace Convoy meetings that escalated to some of the largest in Europe before Thatcher called a halt.

I have been lucky enough, having taken it upon myself to not be another generation that did not ask, to meet and listen to the last few men that fought for our freedom. I can proudly say that at 23 years old I have accumulated stories and memories of sharing laughs with veterans from all corners of WWII. But there was something about the men that temporarily called the 32 airfields of Suffolk home that seemed out of reach. There seemed to be too few left, too far to travel and despite taking part in D Day, Operation Market Garden, Battle of the Bulge and Post-VE Day leaflet drops (in Rougham’s case), there was no major date of celebration.

A warm weekend in July 2015 however, without fanfare or splendor, saw the return of two men of the Mighty Eighth to Rattlesden Airfield, home to the 447th Bomb Group, which Russ Chase and Norman Bussel were a part of.

The airfield is now home to Rattlesden Gliding Club. Parking behind the glider clubhouse, which the two veterans recognized as the control tower that they so often put their lives in the hands of, I toured the military vehicles that had been brought out by re-enactors before enjoying the clubhouse coffee – 30p a cup, what decade was I in?

I got chatting with a fiery American woman named Melanie. Upon mentioning that I had attended on a whim, having assumed the event was for the friends and members of 447th Bomb Group Association, which it largely was, I found myself marched straight down the stairs, across the grass and into the firm handshake of Norman Bussel.

Norm, as it turned out, is Melanie’s husband, 23 years her senior but with no less energy or wit. Over the next hour, as the sun beat down and gliders silently passed overhead, Norm shared his story with me. His memories of Rattlesden airfield were few and far between. He remembers the control tower and the astonishingly large hangar that overlooks our conversation, but little else. Old age and fading memory are not the culprits for this 91-year-old. Norm has little memory of the area simply because he was only there for two months. He was shot down over Berlin on his third mission. He was 19 years old.

With a pass to London and a chance to get away for a weekend, Norm chose instead to enjoy his time off at Rattlesden, and simply relax in a familiar setting. At 4 AM on April 29, 1944, a sergeant woke the sleeping man, “You should have gone to London. All passes are canceled. Everybody’s flying today.” Normally expecting to hear a list of selected names, he wondered, why everybody was flying? Why such a mysterious order? He soon found out. Norm’s target was the big one. Berlin.

As the Mississippi Lady shook through the sky, a young man named Little Joe sat down beside Norm on the comfy makeshift cushion of the latter’s parachute, a welcome break from the cold, hard chairs of the B17. After a telling off from Norm, who understandably wanted his parachute accessible, Little Joe threw it across the radio room and up to the doors of the bomb bay. A little later, the space the parachute had been in was engulfed in flames. If it had not been moved, Norm would have had no hope of exiting the burning plane. He would never get to thank Joe; he was dead. With no call to evacuate, Norm was soaring through the air with four crew dead.

What led to this can only be properly told by the man himself, in this extract from his book ‘My Private War’: “Bill reported incoming fighters and Daddy [pilot] began to call each gunner on the intercom to check if he was firing at the attacking ME 109s. I was shooting my overhead gun in the radio room when Daddy called for me to report. I got out two words, “Yes, I– ” when a burst of flak that must have been right on top of us, blew a huge hole just above the desk where I had been sitting and fragments splattered over my body, knocking me down and ripping off my throat mike…As I stood up, I realized that I was no longer getting any oxygen and then I saw the flames behind my chair and the plane’s skin began dripping molten aluminum. It was surreal to watch the aluminum skin, the metal that appeared to surround us so protectively, suddenly drip, drip, drip like soldering lead. My plane was melting before my eyes. Obviously, our oxygen lines were burning because the fire was so intense. I tried to use the intercom but it was dead. I never heard an order to bail out.”

Seconds later Norm was darting towards earth. Knowing that his clothes were on fire, he allowed himself ten seconds of free fall in order to put the flames out. His plane exploded above him, his friends not only killed but denied the dignity of a body to return home. As he floated through the clouds, unsure in the white mist if he was seeing the afterlife, a thought pierced through his mind: Norm was Jewish. His dog tag proved it. He was heading, unarmed, towards the beating heart of the Third Reich.

Ripping the dog tag from his neck, he threw it into the burning sky and hit the ground with a thump. He was alive, he had made it to earth. Seized by local farmhands, Norm was beaten with rakes and spades and then, in a detail that will stay with me forever, lifted up with a rope around his neck.

The locals, finding one of the men who moments earlier was bombing their homes, full of Nazi propaganda and Hitler’s infectious ideals of a new Germany, were lynching 19-year-old Norman Bussel. With his fingers holding the makeshift noose at bay whilst he gasped for air, a German soldier stumbled on the execution. His orders were simple. “Search him. If he has a gun you may hang him, if not, he becomes a prisoner”. Luckily, Norman had left his pistol on the plane.

The months that followed as a captive of the Germans were full of such cruel treatment of a boy not yet old enough to drink in his home country, that affected him for the rest of his life. Norm’s experiences at Stalag Luft IV cost him decades of happiness as a result of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and created a dark cloud that loomed over the family life he so yearned for.

Despite living seven decades of mental torment, today in front of me stands a strong and charming man that holds the attention of anyone he speaks to. Norm no longer drinks, ordering a non-alcoholic beer from the control tower bar, and amazingly still has his own office within a Veterans Affairs hospital. He has dedicated his life to helping others with PTSD, a new but yet familiar face to greet suffering veterans reluctantly coming forward to file claims for compensation.

There was nothing like that when Norm came back from the war. He was part of the greatest generation, the men that went and came back and got on with a normal life, no questions asked. He suffered in silence, and now in his nineties is choosing to help others. When the men with PTSD come in, they all show the same signs. Shaking knees, fidgety hands, no eye-contact. Norm helps them to open up. Normally talking to people that have never been in combat, the veterans of modern wars see Norm as an old friend that understands what they are going through.

The next day, after a small service for the veterans at a church that proudly flies the stars and stripes beside the numerous memorials to the men of the Mighty Eighth, I headed out of the village. There was to be a memorial service, a re-dedication of sorts. With the relatively small scale of the previous day’s events, I was pleasantly surprised to find a vastly larger audience for the commemorations.

The memorial stands proudly on the side of a small country road, with British and American flags flying over the engraved black stone. It is very similar to the memorials at Brecourt Manor or Foy Woods, which only helped to strengthen the surreality of being not in Normandy or Bastogne but in sleepy Suffolk.

It was there that I met the second of the two men of the Eighth. Seeing Russ Chase from afar, there was no indication of the man’s heroic deeds. But spending five minutes in his company, I was blown away to hear of his no less than 30 missions in a B17. A member, and then some, of the infamous Lucky Bastard club. Russ, as a gunner, only directly shot down one plane. His conscience was clear, he said, from watching with relief in 1945 as the pilot parachuted to safety.

As the country road was shut off and a crowd of family, farmers, locals, and enthusiasts gathered, the two red chairs were filled with the presence of the very last of a generation that slips away beneath us. Followings words from the village vicar, the owner of the airfield who had played a large part in keeping these memories alive for so long took to the microphone. After thanking everyone in attendance, he questioned: “I don’t know how much longer these reunions can go on, but we’ll keep going until they can’t.”

As I’ve traveled around over the past few years meeting these veterans on their final victory lap, there has always been an almost defiant awareness of the urgency of it all. The truth is, no one is pretending this can last forever. There will be the odd few like Harry Patch, who keep going, but realistically the next decade will see the final goodbye of the men from WWII.

I met a man named Len Bloomfield four years ago. He had earned no less than six campaign medals during WWII and was a regular at commemorations. Earlier this year I looked up how Len was doing, and as is so often the case, he had passed away. It was of course upsetting, but the initial sadness was quickly replaced by pride. Pride because Len had died in his sleep, having laid out his suit, lined up his medals and shined his shoes ready for the next day. He was to attend the unveiling of the WWI Tower of London poppy installation. I suppose in a way, he did make it.

As long as these men can keep going, they will be met with crowds, with adulation. Whether at Omaha Beach with the President or at Rattlesden with the villagers, there will be people to wave to. Often I wonder, as I walk through cemeteries, past the graves of the world’s greatest, past the memorial crosses that overlook sites of death and destruction, how long will it last?

We were almost all born in the same century as both world wars. We knew the veterans, we grew up with the stories of our grandparents, our politics are still shaped by the aftermath of defeating fascism. I wonder if, like the cemeteries and monuments of the ancient past we find in archaeology, these sacred places of modern conflict will fall into ruin and disappear. As time passes, as generations come and go and the world wars are 100, 200, 500, 1000 years gone by – will they be kept?

I suppose that is why I fight to keep the memory alive, to record the stories of these last men standing. It saddens me to picture a future archaeologist stumbling across the American cemetery at Meuse-Argonne, with its 14,246 graves of the Great War.

At least for now, as long as air fills their lungs, the men of the greatest generation still have people to meet, stories to tell, hands to shake.

Norman Bussel has written a book about his wartime experiences; My Private War: Liberated Body, Captive Mind: A World War II POW’s Journey.

By John Henry Phillips for War History Online