War History Online proudly presents this Guest Piece from Pietro Giovanni Liuzzi

Much has been spoken and written about that event which saw an entire division forced to surrender to a German tactical group after just over 36 hours.

There was a long trial in Italy that saw some officers accused who, disobeying the orders of the unit commander, opened fire on an approaching German military vessel that caused the beginning of hostilities. Other trials were conducted in Germany, accused were German soldiers reported by the Italian magistrates because they were guilty of violent repression against Italian soldiers who had surrendered. These prosecutions did not succeed.

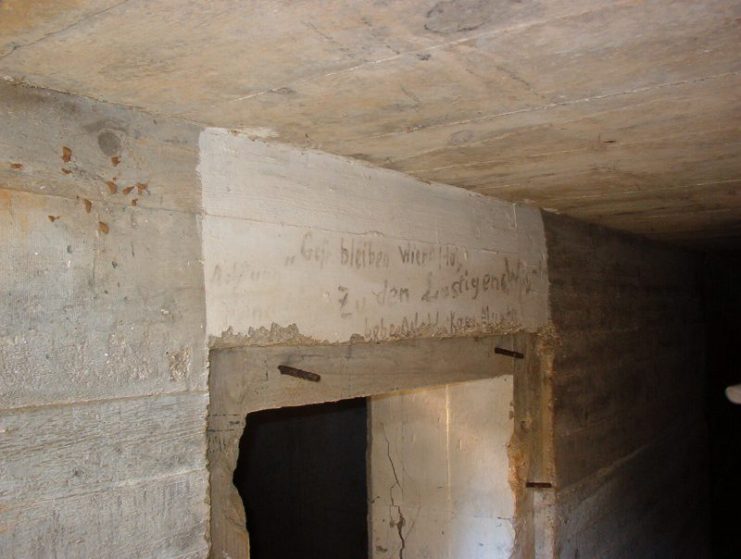

“Captain’s Corelli Mandolin” is the title of a book and a film that have little to do with the real story of Kefalonia. It is irreverent for the killings committed by the Germans: 3800 men killed on the spot is the figure that historians are led to believe correct. Of the 525 officers 390 were shot at the courtyard of the “Red House”; the remainder were transferred to concentration camps in Germany. 8 Italian drivers, commanded by the Germans to transport the 390 bodies of the officers to the beach, where they would then be loaded on boats and then sunk offshore were forced to dig holes in the sand, obliged to consume a meal “after the long fatigue ” showing friendship for the inhumane job they had done and, eventually, were killed and buried in those holes.

The following chapter is an excerpt of the book “The sons of the Mediterranean” which represents a travel diary and describes the itineraries where the clashes took place and what happened to the Italian soldiers.

The latter were on the island as garrison personnel; peasants, fishermen, workers taken away from their activities to fight a war they felt lost. On the opposite side were German soldiers, disciplined, armed and equipped with modern equipment. They were mountain dwellers from Tyrol who hated Italians; they had participated in the battles on the eastern front and prepared for combat. They were enraged for having to make a very long walk from Joannina to Prevesa. But what made effective resistance absolutely impractical was the air supremacy incessantly attacking bare positions. The Stuka hiss froze the blood of any person armed with courage.

The military situation in Italy was fluctuating. The allied landing was going to be a disaster. The units found much resistance in the German armoured forces. From 8 September, landing in Salerno, only on 1 October 1943 the Allies reached the first outskirt of the Gustav Line complex covering only 133 kms. in the plains: the Volturno Line.

So if that was the situation in Italy, how could Allied air – naval units be diverted in those days to support a marginal Italian unit?

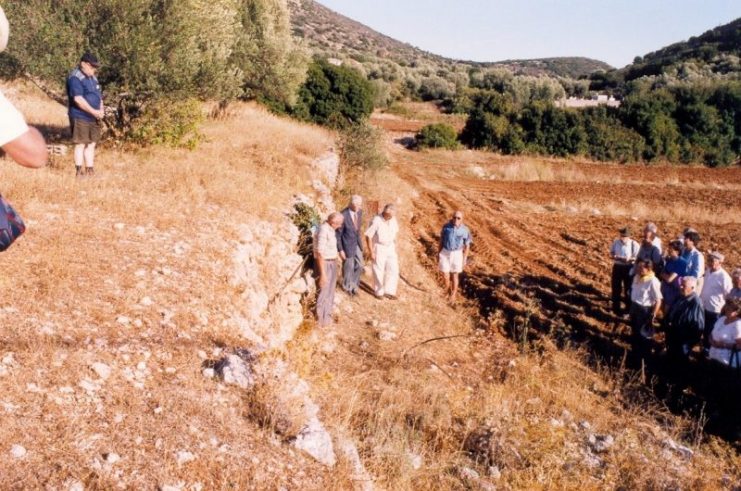

The soil, the stones and the rocks of Kefalonia island are imbued with the blood of Italian soldiers and the marvelous Ionian sea that surrounds it contains the remains of 390 Italian officers and many prisoners sent to Germany by ships which were deliberately sunk as soon as they sailed. Therefore, those who mock the Italian soldiers who found death on that island commits an act equal to the one perpetrated by the German troops.

EVENTS

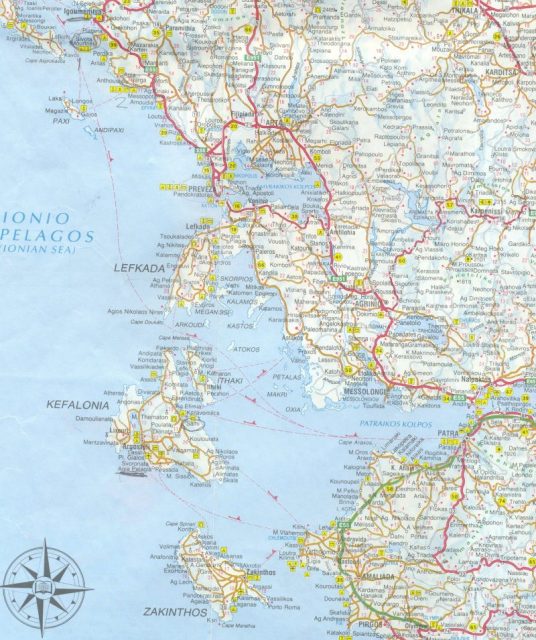

Initially the Italian presence in Kefalonia consisted of the Acqui Mountain Infantry Division which was made up of two regiments (the 17th and the 317th), the 1st Field Artillery Group, a Corps of Engineers, a detachment of the Navy with three coastal batteries, a company of Carabinieri and one company of Guardia di Finanza (the Financial Police Corps). In addition, there were three field hospitals and a surgical unit.

The 3rd Divisional Regiment, the 18th, together with the 3rd Group of Artillery, was stationed in Corfu to provide the garrison. The 2nd Group of Artillery reinforced support in Lefkada.

Eventually, the division was reinforced by three heavy artillery groups and an anti-aircraft unit. The Division Command was located in Argostoli, the main city of the island.

Immediately after the fall of Benito Mussolini on 25 July 1943, the German Army Corp Command ordered the 966th Grenadier Regiment, made up of two battalions, the 909th and the 910th, to be sent to Kefalonia along with a mobile half-track unit and artillery to keep the situation under control and oversee Italian military operations.

Except for the mobile half-track unit, which was temporarily stationed on the Argostoli Athletics Field, and a gun battery in Cape Mounda in the south of the island, the regiment had taken up positions on the Paliki Peninsula.

With the announcement of the cessation of hostilities by the Italian forces against the Anglo-American forces on 8 September 1943, Hitler immediately ordered all Italian units to be disarmed, except for those who were prepared to fight alongside them. In addition, any soldiers who opposed them were to be sent to concentration camps. As far as the Germans were concerned this applied to the Acqui Division and the surrender ultimatum was issued to the Italian forces two days later, on 10 September 1943.

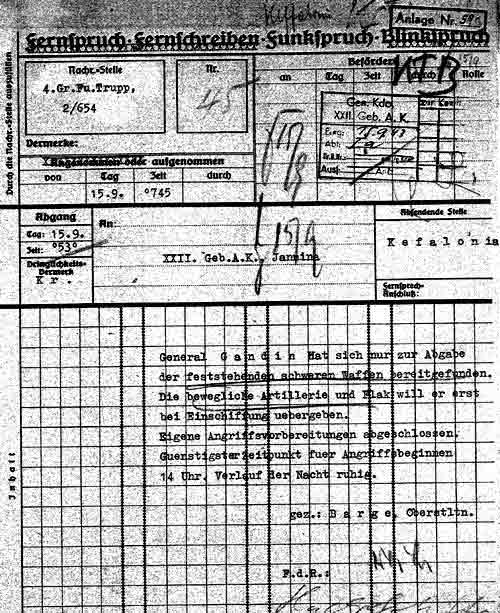

At the time of the ultimatum the ratio of Italian (12,000 men) to German (2,000 men) forces would have allowed an easy victory for the Italians but General Gandin, the Division Commander, opted for a less drastic agreement believing that he would be able to repatriate all of his forces without being disarmed.

Negotiations between the two Commanders were protracted for days. To achieve his aim of armed repatriation and as an act of goodwill to former friends, General Gandin ordered the withdrawal of a company that was defending Kardakata. This was a highly strategic area overlooking the access road to the Paliki Peninsula, the one running north toward Cape Vliaki and the third providing a direct connection to Argostoli.

Once the news of the armistice had sunk in, everyone inevitably began to worry about what was going to happen next. Soon, as there was no apparent movement, a feeling of unrest began to spread which transformed into anger when they learned that the commander had given up control of the Kardakata crossroads to the Germans.

Meanwhile, the German troops, with clear instructions and an unbroken chain of command, had taken action against the garrison in nearby Santa Maura and captured two artillery batteries located along the Paliki Peninsula, the 2nd of the Divisional Regiment in Aghia Georgios, and the 2nd of the 7th Group, located near Havriata. This, along with the news of the capture of all the Italian soldiers present in the area, resulted in a breakdown of discipline. Infuriated infantrymen of one company refused to load ammunition destined for the outlying depots onto trucks because they saw it as a sign of demobilization.

One officer was killed, a hand grenade was thrown at the General’s car, and the flag, a symbol of command, was ripped from the wing of the same car. At this point uncertainty led to chaos; discipline largely vanished and the division ceased to exist as a fighting force.

On top of this, the news that the Italian commander in Corfu had ignored the surrender and had ordered the capture of all German soldiers created an even greater feeling of frustration, especially among the young officers who were unable to understand either the strategy or the indecisiveness.

On 13 September Italian divisional artillery and naval batteries opened fire without authorization on two pontoons loaded with troops and armaments attempting to land in Argostoli to reinforce the garrison located there, sinking them. The military situation had become untenable.

In an attempt to find a solution, General Gandin asked the German Command for embarkation guarantees for the Acqui Division’s fully armed repatriation.

In order to move the negotiations on and having consulted with army chaplains, General Gandin decided to put the question of what to do next to his troops. He asked the men under his command three questions: Did they want to?

– Fight alongside the Germans.

– Fight against them.

– Surrender their arms to the Germans.

The majority of the troops questioned decided against surrendering their weapons, not because they wanted to fight the Germans but rather for fear of being unarmed and at the mercy of either of their adversaries-the Germans or the partisans.

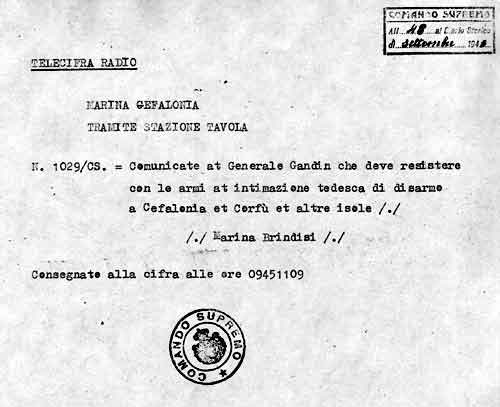

Due to this outcome, considering the lack of guarantees for repatriation and taking into account the actions and the attitude of the Italian commander in Corfu, General Gandin decided to communicate to the Germans that the Division would not surrender or disarm. Then he ordered them to leave the island while he took defensive measures against the new enemy.

Later that day, in the afternoon, German reconnaissance aircraft began flying over and at the same time seaplanes were seen coming in with supplies of arms and ammunition for the Germans.

In an attempt to destroy morale, this was followed by thousands of leaflets being dropped by the Germans on 15 September, inviting the Italian soldiers to desert. These drops were repeated over the days to follow, with no effect.

The reaction of the German High Command in these circumstances was to issue orders that, on capture, all Italian officers were to be shot and that soldiers who refused to surrender were to be transferred to labour camps on the Eastern front. Collaborators, however, were to be given special consideration and preferential treatment.

In the midst of this, no news was received from Italy or from the new Anglo-American allies.

However, a rescue attempt was organized. Two Italian vessels, both torpedo-boats, the Sirio and the Clio were prepared, loaded with support materials and left Brindisi with orders to head for Kefalonia. Before they were halfway there the order was countermanded and they turned back. The Acqui Division was at the mercy of the enemy.

On 15 September, at 2:30 p.m. the Germans took the initiative and launched an attack in two directions: Cape St.Theodoron-Spilaea and Kardakata-Farsa-Argostoli. Tough fighting with followed, with continuous massive air bombardments from the Luftwaffe.

The capture of Kefalonia took precedence over all other targets on the Greek front. All available German aircraft in the area were massed in order to concentrate the offensive on the island. The island was made a priority even over the Corfu front, where the battle for the conquest of that island had already begun.

The attacks were not limited to military objectives. Argostoli was heavily damaged, in spite of the fact that the Italian military command had moved out of the city to do what they could to ensure the safety of civilians.

The German offensive was held and pushed back. The unit operating in the St.Theodoron Area was defeated on Mount Telegraph, just 150 meters high, while the unit operating in the Kardakata – Farsa Area was pushed back to its original position in Kardakata.

For two days the skirmishes and battles gave no advantage to either side, positions being lost and won alternately; then with the arrival of fresh and better-trained units there was a gradual shift in favour of the Germans who had swiftly transferred units from Epirus.

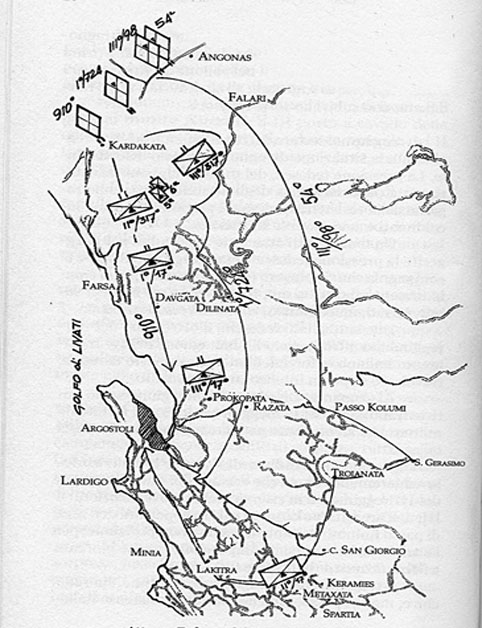

The Command of the 22nd German Army Corps, based in Joannina, sent three mountain battalions to the island: the 1st of the 724th Regiment of the 104th Division, the 54th and 3rdBattalions of the 98th Regiment of the ‘Edelweiss’ Gebirgsjäger 1st Division, literally the ‘Mountain Hunters’. This Division also had a detachment the 3rd Artillery Group of the 79th Regiment.

It should be remembered that the signatories of the armistice agreement with the Anglo-American troops cast Italian forces in the role of rebels in the eyes of the Germans. The inertia and lack of clarity shown by the interim Italian government in deciding whether or not to declare war on Germany only made matters worse for Italian forces on Kefalonia and elsewhere.

This accentuated the violent repression ordered by Hitler, shrewdly interpreted and carried out by his troops to punish the Italian’s about-face. His order was: “Eliminate the Italian bandits!”

On the 16 September, despite strong opposition from the Italian artillery, the first German units succeeded in landing at Cape Akrotiri.

Against continued opposition the Germans rapidly reached the assigned positions to the left of the 910th Division in Kardakata. Further to the north was the 3rd and the 54th, forming the Klebe Tactical Group and between these was the 1st Battalion of the 724th Regiment.

On that same day, the 1st Battalion of the 317th Acqui Division, stationed in Sami, received orders to reach Kardakata and hit the left flank of the enemy forces, the purpose being to weaken the pressure applied against the two battalions of the same regiment, the 2nd and the 3rd, with the objective of regaining the position that had been lost to the Germans.

The departure of the battalion which was scheduled for the early morning was delayed because the convoy of vehicles from Argostoli was subjected to constant air attacks en route. Once the battalion was loaded they set off and were constantly harassed throughout the journey (less than twenty kilometres) by the constant action of the Stukas. The battalion eventually reached the Kimonico Bridge at dusk.

Meanwhile, on the arrival at the front line the 12th Company of the Gebirgsjäger, patrols were sent out on reconnaissance and destroyed the bridge at Kimonico to prevent attacks from the left flank. This halted the passage of the Italian troops marching towards Kardakata. This unit was unable to proceed until the arrival of engineers to repair the way over the river. The decision was taken to position them along the approach road, to rest and begin moving again at first light.

While all this was happening, the 11th Gebirgsjäger Company was preparing to advance, by night, on the hills parallel to the road where the 12th Company was proceeding.

By dawn on the 17 September, the bridge still remained impassable and a decision was made to leave the heavy equipment behind and to move forward towards the objective. The troops left the road and advanced in single file, climbing the slope at the side of the river in order to bypass the bridge.

Air raids began at first light and the unit found themselves completely exposed to the Germans who had moved into position overnight, overlooking the slope on which they were advancing.

The engagement turned out to be fast and furious. Gradually the Italian infantrymen were forced to retreat but managed to regroup in Divarata, having to abandon their heavy weapons in the process.

As the Gebirgsjäger advanced any captured Italians were killed and all the dead stripped of their valuables, this continued during the German advance. The word was quickly spread among the infantrymen that the Germans were taking no prisoners. Only the strongest would be spared since they were needed to carry heavy loads, arms, and knapsacks. All officers were separated from the troops and shot.

The German 12th Company continued on its march and sweeping the Italians from the northern zone as far as Fiskardo, returned to Divarata to face the Italians attempt at stopping their advance.

The Italian defence was overwhelmed, and the line was slowly but inevitably pushed back. The Gebirgsjäger headed for Sami, reached Grizata, and continued on to the Kolumi Pass.

No one was spared. Hitler’s orders were carried out to the letter. Those wounded in battle were killed with a ‘coup de grâce’; bodies were not buried but left to the animals and the elements. One of the surviving officers recorded seeing bodies strewn about in every conceivable position for mile after mile along the way. Some were still wearing bits of their uniform, some stripped naked, all of them dead and covered in blood.

With communications in turmoil General Gandin was unsure of the position on the front line. He decided to instigate a diversion with an engagement at Cape Mounda.

He ordered the 2nd Battalion of the 17th Regiment to send enough units to the southern part of the island to overrun the stronghold held by the Germans. Two companies together with heavy infantry weapons were dispatched and took their positions at dusk on 18 September.

At midnight, the pioneer units moved forward to cut the barbed wire so the troops could advance.

The Italian artillery opened fire on the enemy positions but with little effect on what was a very strongly reinforced position. The German reaction was resolute, violent, and relentless.

All available German units were put into action to push back the attack. The Italian infantrymen fought with fury, but the terrain offered little protection and losses were numerous.

The German lieutenant in charge of the stronghold asked his commanding officer for immediate air support. The action on the ground continued throughout the night, but the next morning brought the air support and the beginning of the end of the engagement. Incendiary and high explosive bombs were used together with low level machine-gun attacks. The exhausted Italian infantrymen succumbed to defeat and were forced to abandon the field, leaving their dead and wounded on the ground.

In the meantime, in the northern sector of the island, German units consolidated their position on the frontline.

At dusk on 20 September, the Klebe Group began their march up Mount Falari with orders to reach the Kolumi Pass by an external route and to surround the Italian units. The other German battalions, the 1st of the 724th Regiment and the 910th, advanced to close in on the enemy around midnight.

Preparations for an attack were also being made by the Italians. Their artillery fire was to start at 4 a.m. on the 21 September, while the attack was to begin at 6 a.m. There were two battalions of the 317th Regiment on the front line, the 2nd covering a stretch from the sea to Mount Kutzuli, the 3rd located at 924 metres on Mount Dafni, and the two companies of the 2nd Battalion of the 17th Regiment, the 5th and the 6th, positioned between Kutzuli and Dafni.

The 17th Regiment had the 1st Battalion serving as reinforcement on the Kourouklata hills, while in reserve there was the 3rd Battalion, stationed in Sarlata, and the remaining units of the 2nd Battalion in Mazakarata.

The three batteries of the 33rd Regiment were drawn up in the Dilinata area: the 1st was positioned at the foot of the mountain, the 3rd near Aghia Vlasis Church, and the 5th received as reinforcement for the group from Lefkada, was in a more advanced position, flanking the metalled road. All of the other artillery units of the Division had remained in their initial positions.

The Klebe Group crossed Mount Falari overnight and continued along the Divarata-Dilinata road. It was still dark when they sighted an Italian camp and in a surprise attack, everyone was taken prisoner. The prisoners were then used to carry the unit’s equipment. They outflanked Mount Dafni and, with the support of the 1st Battalion of the 724th Regiment, they took the Italian 3rd Battalion by surprise as they were completing their final preparations for attack.

There were no real options for the Italian units.

Taken by surprise, out-gunned, subject to mortar fire and withering machine-gun fire, they were forced to surrender despite initial resistance. The officers were separated from rest of the troops and directed to the St. Barbara Gorge where they were shot. The troops were directed to Kardakata, where they too were shot. The plight of the 2nd Battalion of the 317th Regiment, also fighting in this general area, also became untenable. The German pressure from the 910th Battalion, along with continuous harassment from the air, wore down Italian resistance. The prisoners of the 2nd Battalion were lined up and sent off towards Kardakata.

An attempt by the 5th and 6th Company to penetrate the German line and thus to ease the pressure also failed; but only after four or more hours of heavy fighting were they overcome. The survivors, at most 100, were also marched towards Kardakata.

Two German battalions, the 910th and the 1st of the 724th Regiment, faced the Italian 1st Battalion of the 17th Regiment and strengthened by powerful air support, crushed it after an intense engagement.

Communications with Division Command had by this time almost ceased to exist. News reached the Italian Division Command sporadically, mostly given by returning troops who had managed to make it back to the rear.

As a last resort, General Gandin ordered the two battalions of the 17th Regiment which had been kept in reserve, into new positions: the 3rd, in the Prokopata area, and the 2nd to cover the area of the Kolumi Pass.

Only the 3rd actually managed to reach its assigned position. For the other battalion, the manoeuvre was impossible as they were pinned down in Mazakarata by continuous air attacks. The last Italian effort of resistance was in vain. The artillery, which had played a key role in action, ran out of ammunition and was unable to help. At this point, the Acqui Division was annihilated. By this time General Gandin, together with his Command, had moved from Prokopata to Keramies – he had no option but to surrender at 2 p.m. on 22 September.

Lieutenant Colonel Von Hirschfeld, who had directed the operations, won a victory ahead of plan primarily due to complete air superiority. Full of contempt for the Italians he said to his men: “The next 48 hours are all yours”, effectively giving them licence to run amok; something which they took full advantage of.

All photos provided by the author.