By Ludwig Heinrich Dyck / ludwigheinrichdyck.wordpress.com

The Praetorian Guard evolved from the bodyguard of the Republican army commander, the ‘consul’ whose original name waspraetor. When Augustus brought the civil wars to and end and founded the Empire in 27 BC, he joined his own Praetorian cohorts with those of his defeated rival. Billeted around Rome and in the Italian towns, they became the Praetorian Guard. The primary purpose of the Guard was to protect the Emperor and his family. The Guard was usually not used to keep order in Rome, which was the duty of the Urban Cohorts.

The Praetorians were similarly armed as the legions and like them, mostly consisted of infantry with minor cavalry support. Likewise, recruits initially hailed from the Italian heartland, then from the most Romanized provinces and finally from the frontier. Their training was even more intense than that of the legions. In return the Praetorians were less exposed to danger, were able to live in Rome, and committed to fewer years of service. They enjoyed three times the pay of the legions, to to say nothing of the rewards from Emperors eager to curry the Guard’s favors. Numbering 4,500 to 6,000 men under Augustus, the Guard grew to 15,000 under Commodus (r. 180-192) or Severus (r. 193 –211) and briefly again under Maxentius (r. 306-312). Its Prefecture became the most coveted post of Roman Equestrians (knights).

The pro-Republican Augustus had no desire to use his Guard as a terror instrument. The Praetorians rarely even wore their armor; a formal toga being their usual dress. The passive role of the Praetorians rapidly changed after Augustus’ death with the advent of prefect Lucius Seianus, ‘Sejanus’.

During Tiberius’ (r.14-37AD) reign, the ambitious Sejanus concentrated all the cohorts within a new camp at Rome, the Castra Praetoria. The whole Guard was from now on readily available to the Emperors but at a heavy price. Their substantial and constant military presence at Rome gave the Praetorians the power to make or unmake emperors.

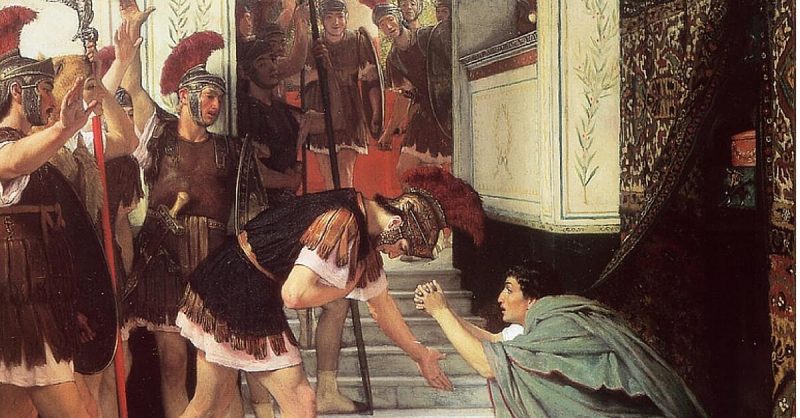

To their credit the Praetorians rid the Empire of many truly undesirable Emperors. In 41 AD a Praetorian tribune (cohort commander) split the mad Emperor Caligula’s jawbone with his sword. As the hapless Emperor lay writhing on the ground centurions finished the job with another thirty sword thrusts. The guard found Caligula’s uncle, Claudius, cowering behind some curtains and promptly proclaimed him as successor. To curry their favor, Claudius rewarded the Guard with five years’ salary! The Praetorians also played their part in the plot to murder the megalomaniac Commodus (d. AD 192) and cut down the degenerate Elagabalus (d. AD 222), throwing his corpse in the sewer.

On the other hand, the Praetorians’ power-mongering often had disastrous consequences. Sejanus used his malevolent influence over Tiberius, to annihilate his own rivals to the throne, including members of the Imperial family. The Praetorian Prefect Gaius Tigellinus (d. AD 68) indulged the debaucheries of Nero and ruthlessly squashed any threat to the depraved Emperor. The Guard was happy to accept a Donativium, a huge monetary bonus, from Commodus’ successor, Pertinax, but then found Pertinax too independent minded. In March 193 AD, after Pertinax reigned for a mere three months, soldiers burst into the palace and a trooper from the Emperor’s elite cavalry guard, the equites singulares, buried a spear in his breast. The Emperor’s severed head was paraded through the streets while the Guard put the Empire out for auction! In AD 217, Marcus Macrinus was the second of four Prefects who managed to become Emperor after he slew Caracalla. Altogether, the Praetorians were at least partially responsible for the death of 15 emperors.

The dangerous game played by the Praetorians could also backfire. The Guard humiliated Nerva whom they blamed for the murder of his predecessor Domitian (d. AD 96 ). Although Nerva bared his own neck, the soldiers only mocked him and slaughtered his friends and associates instead. Nerva’s adopted heir, Trajan, avenged Nerva’s dishonor by putting to death the Praetorian Prefect. In the civil war of 69 AD, the Praetorians went down in defeat alongside the legions of Otho. The victorious Vitellius executed the Praetorian centurions and disbanded the cohorts. He formed a new Praetorian Guard from his own legions and auxiliary troops. Emperor Severus likewise disbanded the Guard and formed a new and larger one with men from his own Danubian legions.

In their defense, the Machiavellian politics of the Praetorian Guard were more a product of, rather than the cause of, the flawed rulers and the civil wars that plagued the Empire. The Praetorians even schemed among themselves; cohorts, officers, and co-prefects were all capable of turning on each other when it suited their needs. Nor were the Praetorians alone in misusing their military might. The legions elevated their own generals to purple, while the Urban Cohorts and the various special body-guard detachments, such as the equites singulares, also played their part in Roman politics.

Under strong Emperors, however, the Praetorian Guard usually stayed loyal, and in civil war or on the frontier earned a reputation as crack troops-their valor is acknowledged on Trajan’s and Marcus Aurelius’ victory columns. On the whole then, like the blades they wore on their sides, the Praetorians proved to be a double-edged sword.

By Ludwig Heinrich Dyck

Sources

Bunson Matthew. A Dictionary of the Roman Empire. New York: Oxford University, Gibbon Edward. The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Vol.I. London: Methuen & Co. 1909, Rankov Boris. The Preatorian Guard. London: Osprey. 1997, Suetonius. Trans. By Robert Graves. The Twelve Caesars. London: Penguin Books. 1989,

Anthony Birley translator. Lives of the Later Caesars. London: Penguin Books. 1976.