War History online proudly presents this Guest Piece from Jack Snowden

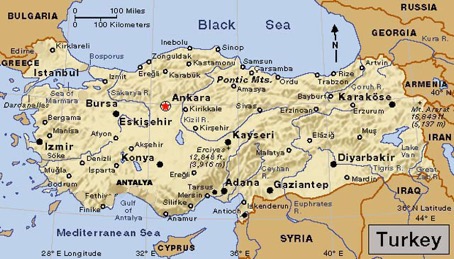

When the eastern Turkish city of Erzurum fell to the Russians in February 1916, during WWI, thousands of Turkish soldiers became prisoners and were sent to camps in Russia. One of them was Tahir Baykal – who took his surname from a near-drowning incident in that Siberian lake.

Over the course of six years, Baykal remained in Russia as a prisoner, fugitive, and then a prisoner once again. Upon his return from Russian captivity, he had to do another stint in the Turkish Army during their War of Independence against Greece. His adventures eventually ended with his safe return to his hometown of Darende in the central Anatolian province of Malatya.

Hearing from Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich in Erzurum;

None other than Russian Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich addressed Baykal and his fellow POWs in Erzurum on February 20, 1916, as Baykal recorded in his notes:

The Grand Duke is coming! The Grand Duke is coming! Nicolayevich is coming! – amid these warnings, we lined up in the hall of the hotel. After looking around with peevish glances, the Grand Duke began to speak in Russian. Next to him was an unimpressive looking fellow, whose accent I took to be that of an Armenian. This fellow conveyed the Grand Duke’s words as follows:

“Fellows, Nicolayevich extends his best to all of you amid your predicament.” Then he said something derisive to the effect that “here are the last military remnants of the Ottomans!” It must have been clear to him that we were hurt by these words so the Grand Duke began to speak more positively about the Turks: “I have never seen any soldiers more brave, more patriotic and more ready to sacrifice than Turkish soldiers. The heroics and skill of the Turkish artillerymen on the slopes of Tortum was something to behold. Don’t be too downhearted about your captivity – it’s an aspect of war that can befall anyone. Don’t worry about your lives. While in captivity you will be well treated. If you want to write letters to your families to tell them you’re alive, we will try to pass them through the front to them. You can be sure of that.”

Life as a POW in Russia begins

After a three-week train ride from a Russian prison camp at Sarıkamış in what was then Russian-occupied eastern Turkey, Baykal began his imprisonment pleasantly enough in the dairy town of Mologa (now under the waters of the Rybinsk Reservoir), northeast of Moscow.

Baykal thought he had a sure-fire plan to get back to Turkey by feigning an illness that would get him repatriated in exchange for sick Russians held by the Turks. He was transferred to a hospital at Voronezh in southwest Russia, but it coincided with the acceleration of the Russian Revolution in September 1917:

With a sudden decision they made all of us prisoners start marching. We didn’t understand what was going on. It was the beginning of September. We walked all the way to Voronezh, where we were put on a train. The Russians were very anxious, hiding anger and worry in their looks. The situation in Russia was very bad. Any moment the government might change. There was confusion and, in fact, there might even be a revolution. For this reason, they might send all prisoners to Siberia or the Far East. It really was not possible to deny this observation. The situation clarified and we prisoners began to be shipped off to Siberia. We headed to Siberia via Tambov, Penza, Samara (Gübiçef), Saratov, Chelyabinsk, and Petropavlosk on the Trans-Siberian railway.

A brush with Drowning and Love

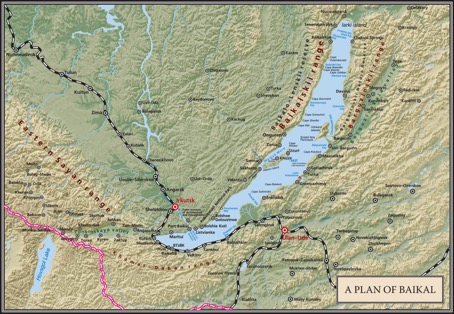

A twenty five-day train ride found Baykal in his next camp, located in a remote spot on the border with Mongolia, south of Lake Baykal, near the city of Naushki – and its infamous neighbor Kahta. Baykal was intrigued by Kahta because there was a town of the same name near his home. Due to the easing of prison discipline in the midst of the revolution, Baykal was able to visit the other Kahta but what he found there proved to be beyond bizarre:

I had heard that Kâhta was a very interesting place. Actually, the name was not foreign to me because there is a town named Kâhta near the ruins of Nemrut Dağı, one of the seven wonders of the world, near my home in Malatya. So this likeness of the names sparked my interest. I tried very hard to get permission from my guards to visit the city and finally, toward the end of March 1918, together with a few friends we set out for Kâhta. As we approached the city center we were met by an increasing putrid smell that even increased in its unpleasantness as we went deeper into the city. I tried to limit its impact by putting my arm over my nose. Above us, birds of prey were circling and diving continually. There were packs of dogs, as well, behind a wire fence which enclosed a kind of cemetery where there were decaying human bodies strewn about and piles of human bones, as well as human hair blowing in the wind. What kind of belief would allow for this! It is said that the Russians, wanting to exploit this scene, have asked the Orthodox Missionaries to open a mission here to ‘save’ these ignorant sinners. Actually, the Russians secretly want to conquer Kahta from the inside by this sly method.

Concerning the camp at Naushki, Baykal recorded:

We were settled into the ‘logar,’ or prison camp, which was quite large and crowded: 18 Turks, 500 Austrians, 15 German officers, 5,000 soldiers. The most senior officer was an Italian named Colonel Napolyon. I stayed here for about one year, until the end of March 1918. Afterwards, I went to Berezofka military garrison in the city of Verkhneudinsk, in the vicinity of Lake Baykal, where I stayed for a short while.

Baykal’s stay in Verkhneudinsk (Ulan-Ude) was eventful for several reasons. He nearly drowned while swimming in Lake Baykal, later taking it as his surname to remind him. And he met a lovely Tatar girl named Aliye whom he almost took with him back to Turkey:

I couldn’t stop thinking about Aliye day and night. With her personality and attractiveness, she had drawn me to her like a magnet. She was the daughter of Abdurrahman Hamurcin Efendi, who was the chief of the national income administration in the city where we were located. He was between 45 and 50 years old, an intellectual and a revolutionary. He had a big flower store in the center of the city. Hamurcin was originally from Boğoroslan town in Kazan Province and had come here to get into business. His daughter Aliye had finished high school here. This love would bring me back to this historic house many times! In short, I was head over heels in love with Aliye and had become her ‘Mecnun’.

Nevertheless, Baykal was determined to take his chance as a fugitive hoping to get back to Turkey via Vladivostok and America:

The tumult and lack of authority in Russia had created a situation that was in tune with my escape plans. I made the decision to escape and would not relent on this decision. I gathered up all of my personal belongings, carried what I could and distributed the rest to my friends. Then I boarded a train heading east.

Baykal’s ‘Great Circle’ failed escape route from and to Ulan-Ude;

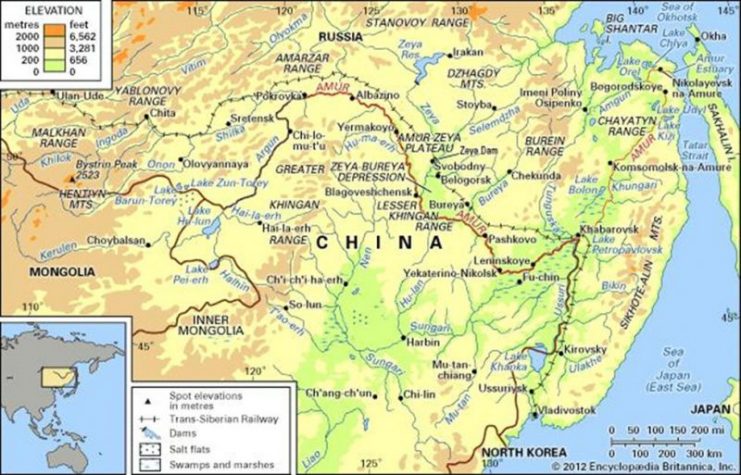

Baykal left Ulan-Ude and made it as far as Chita, where he got caught up in a tense situation involving opposing factions of the Revolution:

After a while, we came to Chita Province, and there were a number of trains waiting at the station there. A crowd of students and youths had been organized here, determined to catch any Bolsheviks trying to escape to the east and to seize ammunition and money. With money I borrowed from my friend I hurriedly filled my stomach at a restaurant in a nearby hotel. I went to the bathroom to wash my hands and was startled by the sound of gunfire, so I gave up the idea of washing my hands. The gunfire filled my ears and it seemed it was coming from the forested area to the east of the city. We were quite anxious about this gunfire and I decided to find a place to hide myself, rather than continue the train journey. I ran to the train to grab my belongings and then consider my options. The station was in an uproar. Russian soldiers had taken up their weapons and were posted at every corner. They placed machine guns at the intersections in the city. There were also some small-caliber cannon, as well.

Similar tumultuous scenes met Baykal as he continued his train journey eastward through Sretensk, where he obtained a Russian ID card with the help of a friendly Caucasian, and onward to Blagoveshchensk:

Henceforth I was Russian citizen Esadullah Kaçayif and half-way to freedom. Nevertheless, I knew that I had to be very alert and careful, so that is how I behaved. With this document I roamed around Siberia and the Russian plain for about two years comfortably. But I wanted to go to America from Siberia and from America to Turkey. In order to do this I had to make my way to Vladivostok and two days later I was in Blagoveshchensk, where I was hosted by Circassian from the Caucasus.

Fortunately for Baykal, the Japanese reached Blagoveschensk on September 19, 1918. Calm having been restored there, Baykal was able to take a ferry to Harbin, China, from where he hoped to travel to Vladivostok – and America.

Prison years in Moscow

But Harbin proved to be a dead-end, as far as access to Vladivostok was concerned, so Baykal headed back to Russia via Manchuria, all the way to Ulan-Ude where he reunited with his beloved Aliye. Taking her with him was beyond problematic, though. Baykal pressed on alone westward, landing in Perm:

I noticed that I had reached as close as 70-80 kilometers to the front opened between the warring Bolshevik and Kolchak factions. At this time, the western side of the Ural Mountains was in the hands of the Bolsheviks and the east side, Siberia, was held by the Kolçak forces. My path’s advancement was tied to moving the front forward or backward. My only chance was to wait patiently and not act rashly so that’s what I did.”

The Bolsheviks eventually took Perm and through a chance association with a German spy, Baykal was arrested and sent to V.C.K. Prison, in Moscow. He describes the jail as follows:

Moscow Prison became my abode henceforth. They quickly took my statement, separated me from the German officer and put me in a different cell block called Anushka. My dark, dank room was the size of a small toilet and had a steel door. Inside the room was a portable bed with a ragged old sheet and a table about half a square meter in size. The grass that filled the bed was sticking out of it. The floor was covered with slapdash cement that was cracked in some places and there were holes, as well. Rat holes could be seen all around and especially at night the rats ran wild. The grass-filled pillow was covered with spider webs. On the bed was a worn out blanket with lots of holes and the walls were covered with radiator pipes that dripped water constantly.

Baykal’s time at Moscow Prison ended, but only because he was moved to a prison on the outskirts of Moscow called “Ivanof Monastery,” primarily for foreign political prisoners. Baykal was the only Turk there but his status resulted in an unusual assignment

The days that I tried to get through living in the Ivanof Prison were not much different from my previous days in V.C.K. prison in Moscow. There was a rumor going around that the Khan of Khiva and his entourage were coming to visit the prison. One of the prison guards grabbed my arm and said “can you translate for us? They’re Uzbek Turks like you.”

The Khan’s ‘visit’ was, in fact, his imprisonment, after the Bolsheviks dethroned him when they took Khiva in early February 1920. In any case, Baykal served as the Khan’s interpreter at Ivanof and learned years later that the Khan had died of hunger there.

Return to Turkey – but no end to soldiering

Baykal was finally released from imprisonment in Moscow and summarized his time in Russia as follows:

It was early January 1921. It had been more than six years since I first fell prisoner to the Russians in February 1916. I had experienced very difficult days, months and years and struggled mightily. Before today how many times had I nearly died, only to be revived again. Now, though, I was starting life all over again, having left behind those horrible dark days, with a new lease on freedom. I was the happiest person in the world, no one could be happier. Oh, were I able to set foot in my homeland, I would not be able to describe my joy. I would get help and support for this from the Turkish Embassy. Without wasting a moment, together with another Turkish officer who was in similar circumstances, we went to the embassy to tell the officials there about our situation. They did what they could to help us. The two of us went via the Kiev-Ukraine road to Novorossiysk, an important port on the Black Sea coast, and settled into a modest hotel there. We didn’t know what to do so we spent 10-15 days just hanging around. But we found ourselves waiting without much hope. This port city had become a center for gathering Turkish prisoners and, like us, Turkish officers and soldiers were pouring into the city, waiting desperately to return to Turkey.