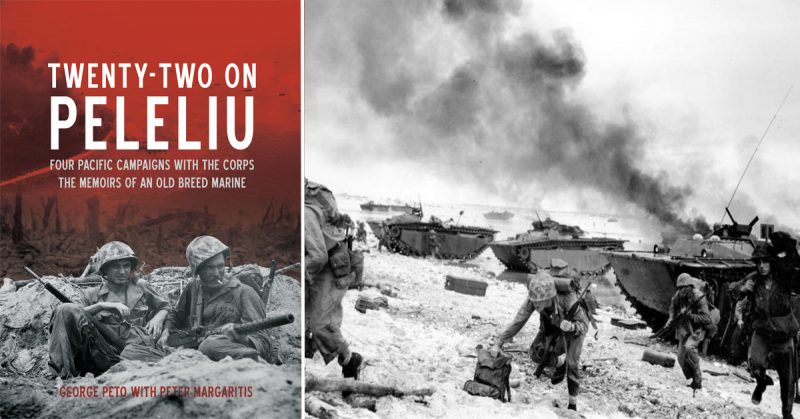

War History Online proudly presents this Guest Article from George Peto.

This is what it was like to approach the bloody beaches of Peleliu.

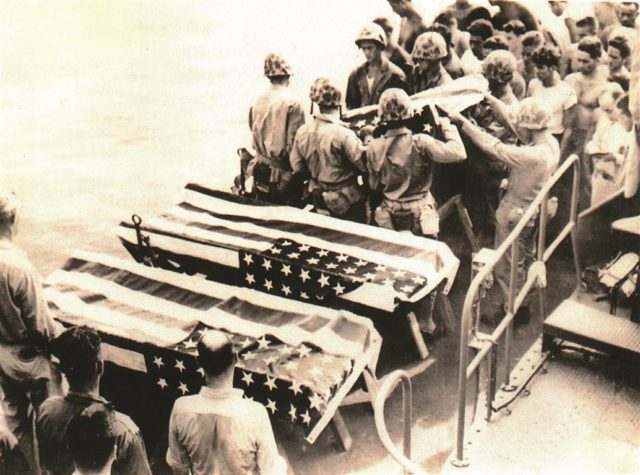

The following extract is taken from Twenty-two on Peleliu by George Peto with Peter Margaritis, about George’s experiences as an Old Breed Marine on four Pacific campaigns in World War II. Here, he describes what it was like to approach the beach at Peleliu in which more than 2,000 American soldiers would give their lives to secure.

Our amtrac slowly moved into position with the others, to make their three-mile run to the beach. With our amtrac bobbing up and down on the waves, some of us began to get unsteady from that rocking and rolling. Between moving around in the water and just plain being nervous, a few of the guys got really ill and ended up chucking that beautiful navy breakfast.

It was now around 7:45 a.m. Our amtrac joined others as we puttered around in a circle, with more coming over to join us. Then someone gave the signal, and we formed up in a line and began to move towards the island. As we headed toward the beaches, I could see a lot of smoke rising. The warships had been pounding the Japanese positions for the last few hours. I liked seeing those battleships firing, like the USS Iowa, with her 16-inch shells whooshing overhead.9 Supposedly, the navy had hit them pretty hard over the last few days, but I knew better. This was not going to be a cakewalk.

I was in one of the lead amtracs, along with K Company commander Capt. George Hunt, and our mortar platoon leader Lt. James Haggerty, with his bright red hair showing under that damn blue baseball cap that he always wore.

I went over again in my head what I was to do when we landed. My job was forward observer for the 81s, so I would have to make contact with them as soon as I could to set up fire missions.

We kept going in, the amtracs all moving slowly. The navy was still keeping up their bombardment and we were grateful for that. As we came nearer to the island, I could see in front of us a few hundred yards offshore white waves crashing onto the coral reef that surrounded the island. Our amtracs were supposedly designed to be able to waddle up to the reef, crawl over it, and keep going until they hit the beach, where they could creep up onto the sand and let us out onto dry land.

When we were about a half a mile from shore, we heard an artillery round whizz in from the island and pass low over our heads. We looked at each other and hunkered down into the amtrac, as the driver began to speed us up. We now approached the coral reef at a faster pace, about four knots. I began to notice splashes in the water around us. The Japanese reception.

“That’s Japanese stuff,” one guy said.

“You ain’t kidding!” somebody else said.

We came up to the coral reef. Although we seemed to be plodding along, we were going faster than I realized, because when the amtrac hit the reef, it felt like we were ramming a brick wall, and we all staggered forward, slamming into each other, trying to keep from falling. As the tracks began to grind into the coral, the amtrac slowly began to crawl over the reef, the engine straining as we inched forward. A shell landed nearby, and the driver shifted gears into low. Our nose began to creep up as the treads took hold and we moved onto the reef, to the point where we began to have trouble standing.

The amtrac kept climbing up and we struggled to keep from falling backward, until finally the stern was so low, sea water began to splash up over our tail and into the well. Cold water starts to swish around our ankles and we started to stumble as we moved forward. Finally, thank goodness, we made it over the top of the reef and fell forward with a crash. We cleared the reef, and then began our final run to the beach, about 300 yards away. We just looked at each other and shook our heads.

As we approached the shore, Japanese artillery and mortar rounds intensified, and I could see geysers spew up as they hit around our landing craft. Looking ahead, I could see that a couple amtracs had already been hit on the reef and were now burning furiously, and there were men around them desperately trying to make it to land. So far, we were the lucky ones.

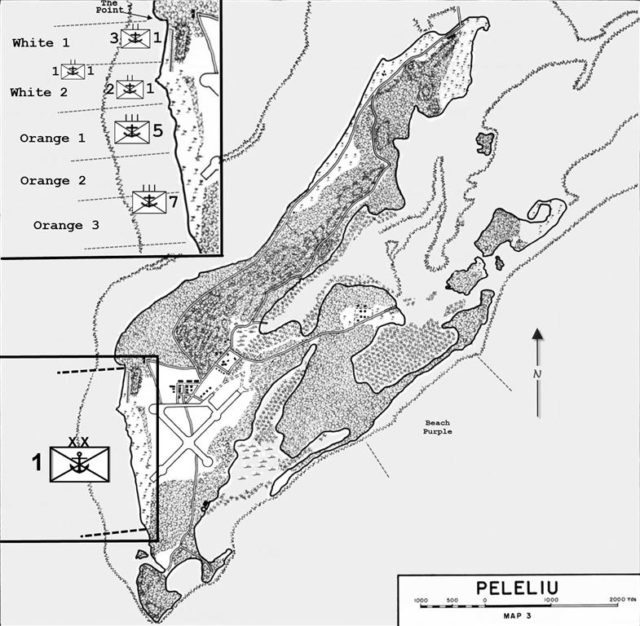

The temperature climbed and more shells occasionally landed close by as we approached the shore, and sometimes a pew-pew-pew as machinegun bullets hit the water nearby. We finally made it to the beach, as the amtrac crunched up onto the sand and stopped with a jolt. Our battalion was the first to hit the shore, landing on the left flank at exactly 8:32 a.m., about two minutes after the scheduled H-Hour. We were followed shortly by the rest of the regiment, then the 5th Marines in the center, and the 7th Marines on their right.

We had finally made it to the beach. To get out, we had to climb out of the passenger well and go over each side. The eight-foot drop was not fun, especially if you had to land on something like sharp coral. A few moments after we landed, and with an occasional bullet clanking into the amtrac, we started to get out. I slid over the side and crunched down on a spongy, sandy coral surface. The jump was bad enough, but the guy that followed me landed partly on my back, driving me into the coral.

After I shook my head and got my eyes focused and back into their sockets, I stood up and ran forward as bullets zipped above us and occasional mortar rounds landed here and there. A bunch of us moved up the beach about 30 yards and dove into a tank trap that ran parallel to the shore. The tank trap quickly filled with other guys like me, and we all crunched down. More guys came ashore and those not immediately hit came up behind us, hitting the dirt and then starting to dig in along the sand. I looked around and saw a number of bodies that were just lying on the beach or floating in the surf.

George Peto passed away peacefully in his sleep on the Fourth of July 2016.

You can click here or here to purchase his autobiography Twenty-two on Peleliu: Four Pacific Campaigns with the Corps: The Memoirs of an Old Breed Marine from Amazon.