Throughout the war, the Allies enjoyed a certain advantage over the Axis that was purely the product of geography. Because the Allied nations occupied real estate on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean, their meteorologists were able to benefit from communicating with each other about weather patterns.

Prevailing weather patterns in the Northern Hemisphere generally move from west to east. During World War II this meant that a weather station in Canada could observe a particular weather event and then pass that information on to a station in Iceland, which could, in turn, pass it on to British meteorologists on the other side of the Atlantic.

Thus, the Canadians could tell the British what kind of weather was on its way to Europe. On countless occasions, this information was decisive in helping the Allies operate informed as to climactic conditions. Conversely, the German navy enjoyed no such advantage since its meteorologists could reach no further west than France’s Bay of Biscay coast.During the early years of the war, this issue did not present such a problem because Kriegsmarine U-Boats and surface vessels all over the world enjoyed a terrific operational advantage and were capable of sending in weather reports.

The German navy’s dominance slipped as the war developed though and, as the hunter became the hunted, it transitioned from the offensive to the defensive. In the defensive/reactive mode, accurate weather forecasting became more critically important than ever to Germany.

The need to fill in this weather gap led the German military to explore the possibility of establishing secret weather stations on the North American continent. During the latter half of 1943, the German Meteorological Service developed the design for a weather station that could be deployed to remote Arctic islands like Greenland and Svalbard.

Produced by the Siemens Corporation, the design was completely automated, portable and capable of being packed through the narrow hatches of a U-Boat. After tests of the prototype had resulted in an initial success, it was decided that the device would be installed in a remote area of northern Canada. Shortly after that, U-537 departed Kiel on Germany’s Baltic coast with a station aboard.

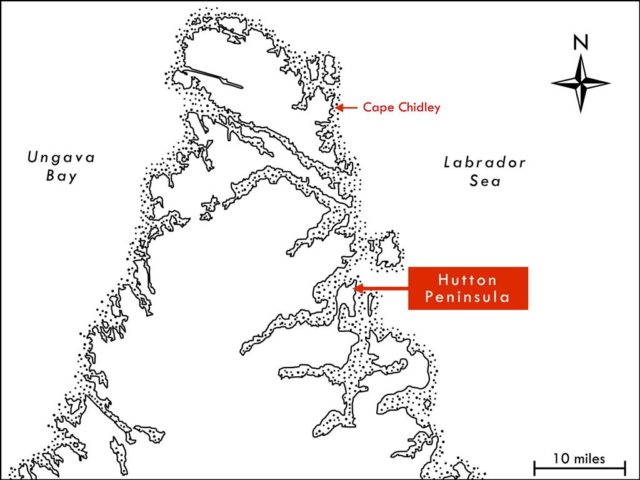

After calling briefly in Bergen, the U-Boat departed on October 9th and continued on toward its destination: the Labrador coast. The timing of this mission was critical and called for the station to be deployed in late October while the coastal inlets near Cape Chidley remained unfrozen. Shortly after installing it, those inlets would freeze over with the coming winter making it all the more unlikely that the Canadian authorities would either locate or dismantle the station.

The area chosen for the weather station was so extremely remote that it had only recently been surveyed. In 1931, the National Geographic Society launched a program to survey coastal Labrador. The survey also sought “to carry out the field work necessary for testing the new method of producing topographical maps from oblique aerial photographs.”

Using a Fairchild seaplane equipped with the most modern cameras available at the time and a supporting research ship, the survey crew began working each summer season when the weather cooperated. Working their way north with each season, the survey’s ultimate destination was Killiniq Island where the Labrador Sea meets Ungava Bay. The east coast of the Labrador Peninsula is dominated by hundreds of fractured fjords, inlets and treacherous shoals.

Cape Chidley itself was later described as being “steep and bold on all sides,” by a member of the team. To a large degree, the intense nature of this coastal geography was responsible for the lateness of an official and organized survey expedition. Even before the National Geographic team reached as far north as Killiniq Island and the infamous rocky cape located there, an interesting discovery was made.

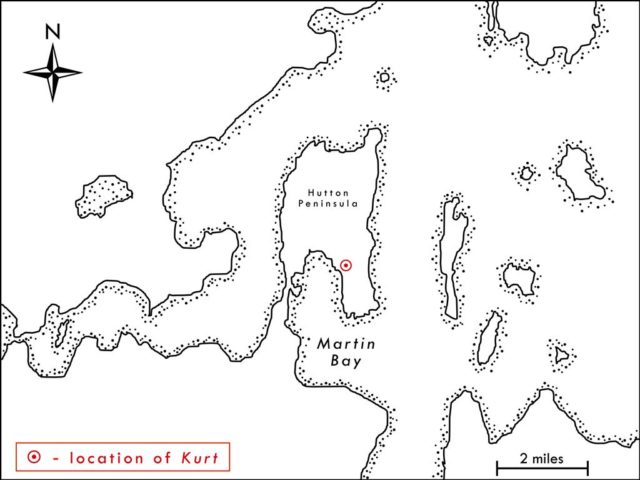

In 1934, a ship captain anchored in “an excellent and probably hitherto unexplored harbor south of Cape Chidley.” Locating and charting that harbor was one of the many objectives of the NGS survey because it could serve as a safe anchorage for the regular shipping traffic traveling between the St. Lawrence River and the commercial markets of Europe. So in 1935, the survey team explored and charted the area near Rowland Point, the Hutton Peninsula and the mouth of the Ikkudliayuk Fjord.

What the survey found there was an anchorage at 60º04’05”N, 64º23’06”W with a natural depth of as much as 42-feet between the east coast of the Hutton Peninsula and the lee of Oo-olilik Island – it was called Attinaukjuke Bay or Martin Bay and it was the “excellent and probably hitherto unexplored harbor” identified in 1934. It was also the destination of U-537 in October 1943.

When Kapitänleutnant zur See Peter Schrewe steered U-537 out of Bergen at the beginning of that month, he had no way of knowing what danger and excitement the next three weeks would hold. He was in command of 48 men on a Type IXC/40 U-Boat that was manufactured by Deutsche Werft AG in Hamburg between April 1942 and January 1943. The 87 IXC/40 U-Boats commissioned into Kriegsmarine service during World War II represented a product improvement over the Type IXC.

The improvements largely related to increased fuel carrying capacity (which increased overall cruising range to approximately 13,850 nautical miles) and enhanced anti-aircraft armament. In addition to the single mount 2cm Type 30 Flugabwehrkanone (anti-aircraft canon or “FLAK”) on the tower superstructure, the IXC/40s were up-gunned with the addition of a platform aft of the tower that accommodated a Flakvierling 38.

This weapon was a flexible quadruple 2cm anti-aircraft gun mount that more than doubled the Type IXC’s ability to defend itself from aerial threats. With four weapons simultaneously firing 2cm projectiles at a cyclic rate of 450 rounds per minute, the Flakvierling 38 was capable of a cumulative cyclic rate of fire of over 800 rounds per minute. In other words, it was a weapon that could put a lot of lead in the sky at one time against an attacking airplane and it made the IXC/40 an extremely dangerous target.

When U-537 departed Bergen, the submarine’s route took it west across the North Sea above the English isles. Between the Faroe Islands and Iceland, the U-Boat entered the northern stretches of the Atlantic Ocean. This route was far less traveled and promised a somewhat safer Atlantic crossing than the more heavily patrolled shipping lanes further to the south.

At 8:48pm on October 7th, U-537 transmitted a message to U-Boat headquarters (the Befehlshaber der Unterseeboote or “BdU”) announcing that it had crossed 20°W. Interestingly, cryptanalysts at Bletchley Park intercepted that message and a series of messages that followed. In connection with the mission to deliver the weather station to the Labrador Coast, Kapitänleutnant zur See Schrewe had been ordered to radio in at prescribed points along the way to receive instructions.

One of those points was 20° W. The following afternoon, Schrewe was given the instructions “onward passage in accordance with special task.”Although the British intercepted and read the message, they had no idea what the “special task” was. The “onward passage” part of the message meant that U-537 was to continue en route to Canada.

Ironically, the U-Boat entered a truly wretched patch of foul weather characterized by high wind, strong rain and extremely cold temperatures resulting in several of the crew becoming terribly seasick. The storm also had the affect of slowing the progress of the boat to a crawl.

On October 12th at 6:36 pm, Schrewe received a rather complicated set of instructions directing the U-Boat “to simulate a battle group” in a specified area by surfacing intermittently and broadcasting false wireless transmitter traffic in the form of daily weather reports. After sending one wireless message, he was ordered to submerge and move to another location and repeat the process a few dozen times.

The whole ruse was designed to create the impression of a large Kriegsmarine naval task force operating in the area. Obediently following orders, Kapitänleutnant zur See Schrewe completed the mission as instructed despite the fact that conditions were appalling for all aboard each and every time the U-Boat surfaced to send in the radio report. When U-537 surfaced just after 2:00pm on October 14th, large swells pounded the boat.

One of those swells struck with such power and violence that Flakvierling 38, a 3,300-pound weapon, was ripped from its mounts and thrown overboard. When Schrewe transmitted a message informing the BdU about what had happened, the reply questioned where the weapon had broken loose and whether or not it had been properly stowed.

Schrewe replied by responding to the questions, and Bletchley Park intercepted all of it. The British therefore knew that U-537 was out there in the North Atlantic on a “special task” and that it had just lost its primary anti-aircraft gun. It was valuable intelligence information but nothing could be done about it.

At 11:49 am on October 17th Schrewe surfaced in the North Atlantic at a pre-arranged location and transmitted his position as 59°N, 48°W, which placed U-537 in the Labrador Sea just off of the southwestern tip of Greenland. The reply came at 11:53 am the following day and said simply “onward passage to execute special task” which represented the final go order for the U-Boat to approach to the North American coast.

Schrewe and the crew of U-537 then continued on toward Cape Chidley. Because of the continuing foul winter weather, progress was slow and it took another four days for the U-Boat to cover the distance.

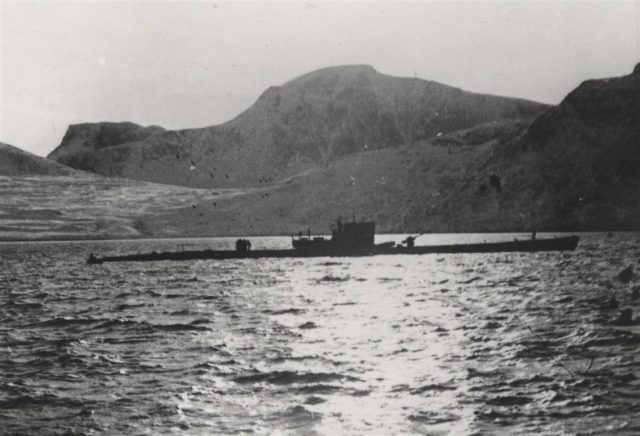

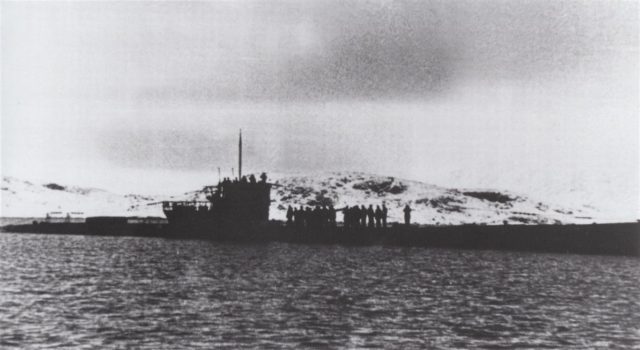

Early in the evening of October 22, 1943, though, U-537 anchored in Martin Bay. The crossing had been time-consuming and arduous, but it had been brought to its successful conclusion. Though the Flakvierling 38 was a bygone memory, U-537 rode at anchor in protected water in North America and it was time to complete the “special task” so cryptically mentioned in the transmissions from the BdU.

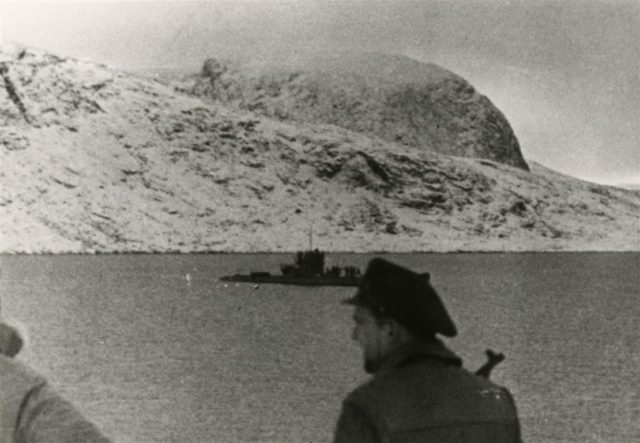

Kapitänleutnant zur See Schrewe immediately sent a party ashore to post a lookout and scout a site for the weather station. An MG-15 machine gun was placed on the heights overlooking the bay to provide some measure of protection and early warning for the U-Boat riding at anchor in the cove below. A clear spot on the summit of a 170-foot tall hill 400 yards inland from the beach was selected for the site of the station.

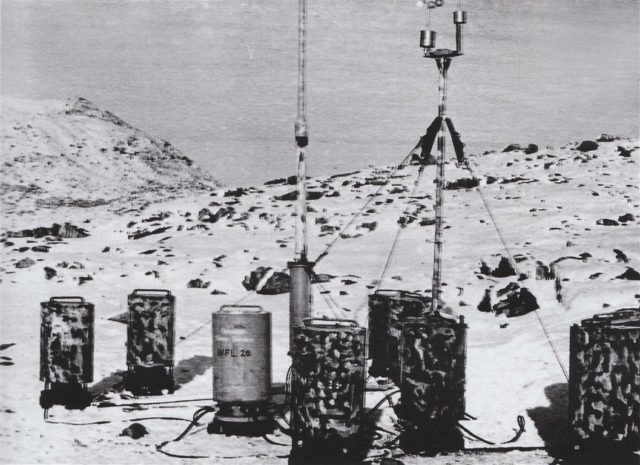

At dawn on October 23rd, the daylong process of installing the device began. The package was a Wetter-Funkgerät Land-26 (WFL-26) nicknamed Kurt by its designer. It consisted of several pieces: a 10-meter tall mast mounting an anemometer, a tripod for the mast and ten cylinders containing other weather instruments as well as a 150-watt transmitter and dry cell, high-voltage batteries. Once assembled, Kurt would record temperature, humidity, air pressure, wind speed and wind direction data and transmit that information to receiving stations in northern Europe every three hours at 3940 kHz.

Along with two technicians, Professor Kurt Sommermeyer from Siemens accompanied U-537 on its rather uncomfortable and unpleasant Atlantic voyage. First thing in the morning on the 23rd, that team went to work with the help of several sailors getting Kurt ashore and up to the top of the hill. Because they weighed 220 pounds each, it took time and muscle to bring the cylinders up from below and place them aboard the launch that then delivered them ashore. More time and muscle were needed to move the cylinders from the beach up to the hilltop site where Kurt would be assembled.

As soon as all of the pieces of the Kurt package were in position, Professor Sommermeyer and his technicians spent the rest of the day assembling and testing it. Each of the pieces of the WFL-26 station were marked “Canadian Weather Service” which is noteworthy because no such government entity existed at the time.

By late afternoon everyone was back aboard ship, which allowed U-537 to weigh anchor and depart at 5:40 pm, ending the only German invasion the North American continent has ever known.

U-537 then cruised out to sea far enough to submerge completely, and then paused on the bottom long enough to confirm that the 150-watt Lorenz FK transmitter was broadcasting.

Kurt was in place and functioning. Earlier that morning, Kapitänleutnant zur See Schrewe received a message from the BdU that instructed him as to what to do next: On completion of task move off 300 miles and report execution by short signal. Then freedom of action in square Gruen UE and to eastward thereof.

With the “special task” successfully completed, U-537 was given freedom to hunt for targets of opportunity during the return voyage to Europe. Morale on board was at an all time high, but not for long because with Martin Bay only two days behind them, the Germans determined that Kurt was no longer broadcasting. Schrewe insisted on periodically surfacing to check for a signal, but there was nothing.

Not willing to accept defeat, Germany made another attempt the following season when the second Kurt was loaded aboard U-867 in early September 1944. With the plan that it would be installed in roughly the same area on the Labrador coast as the first Kurt, the U-Boat would follow the same basic route that U-537 had the previous year. But U-867 never reached its destination after a B-24 Liberator bomber from RAF 224 Squadron sank it northwest of Bergen, Norway on the 18th of the month.

As interesting as the U-537-Cape Chidley–Kurt story is, the epilog to that story is really the best part. In the late 1970s, a retired Siemens engineer named Franz Selinger began compiling research material so that he could write a history of the company. During the course of his research, Selinger reviewed Kurt Sommermeyer’s personal files and, in so doing, discovered documents and photographs relating to U-537’s installation of the weather station on the Labrador Coast in 1943.

His curiosity aroused, Selinger wrote to Canadian Department of National Defence historian Dr. W.A.B. “Alec” Douglas in 1979 inquiring about the status of the device. Douglas then began a search for records relating to the weather station, and when none could be found a plan was made to visit the site.

In July 1981, the Canadian Coast Guard Heavy Arctic Icebreaker Louis S. St-Laurent carried a team to 60º04’05”N, 64º23’06”W and landed them on the Hutton Peninsula by ship’s helicopter. There they found the weather station sitting in the same spot where U-537 had left it thirty-eight years earlier. Although it had been tampered with and partially vandalized, all of its component parts remained intact. Everything was then hoisted back to the icebreaker by the helicopter, and then eventually Kurt was added to the collection of Musée Canadien de la Guerre in Ottawa as Object Number 19820219-001.

It was ultimately restored and placed on exhibit in the museum, reminding us of that fleeting moment when Nazi Germany put an armed landing party ashore in North America.

Author: Marty Morgan