BACK WHEN YOU COULD COUNT the number of trimix divers in the UK on the fingers of two hands, I began working on a list of important shipwrecks made accessible by this new diving technology.

The wrecks had to be naval and of significant historic importance if I was to invest time in looking for and diving them. Among the notables was the British submarine M1, which I found in 1998. However, one of the most important, HSK Komet, remained undiscovered for more than a decade and took much effort to track down.

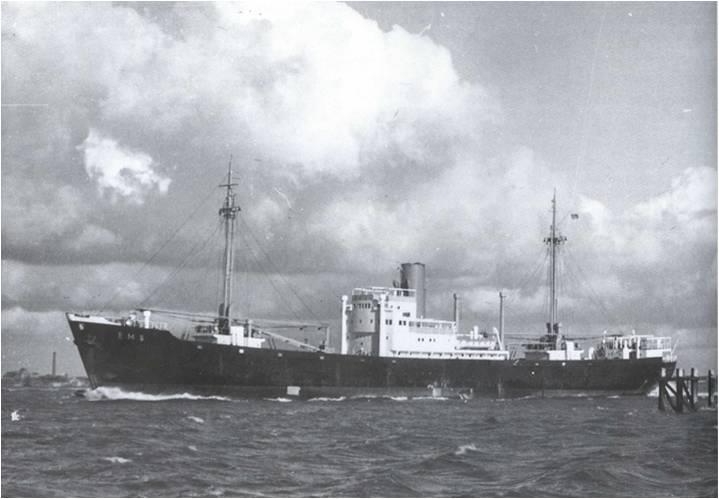

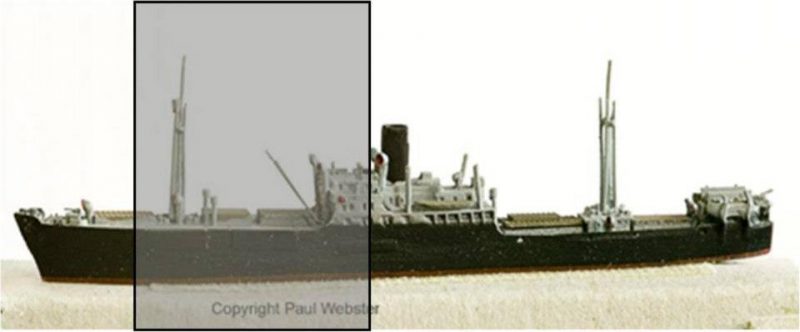

As the second largest (after HMS Charybdis) naval war-grave in the Channel, it was a great reward finally to locate the wreck and put it back on the map. An Auxiliary Raider, Komet was one of nine merchant ships that Germany’s Kriegsmarine converted for military service in 1940-41.

It was following in the footsteps of the Imperial German Navy, which had enjoyed much success with raiders in World War One.

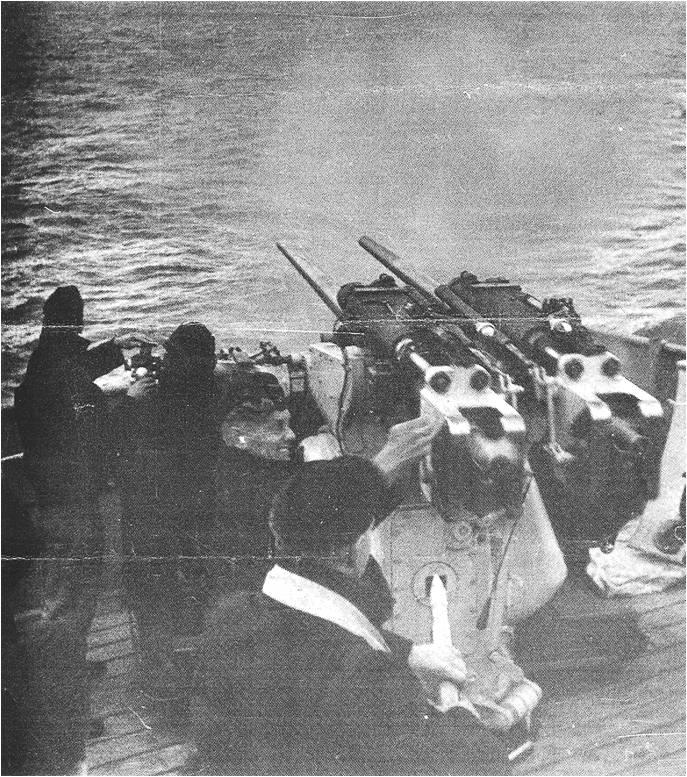

The Captains of raiders such as Moewe and Seeadler became world-famous for their exploits. The Raider program was simple. The idea was to convert merchant ships into powerful warships that looked like innocent freighters.

They would have the ability to change disguise to look like any number of foreign-flagged merchant ships, and the hidden armament of a cruiser. Their purpose was equally simple – to sink as much enemy merchant shipping as possible, while avoiding encounters with hostile navies.

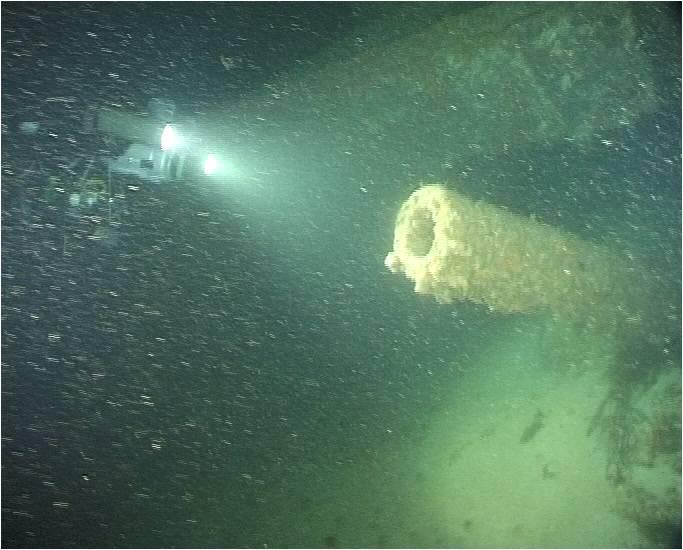

The Komet project will always be one of my favorites. It took years to track down and was an extremely challenging series of dives. Situated off Cap La Hague in one of the most tidal stretches of water on the planet the dives were thrilling but potentially dangerous.

I was grateful for having a great team of divers and a great boat and crew in MV Maureen. In this shot Paul Webster has nicely caught our drift decompression system (Paul Webster)

The raiders operated from 1941 to 1943, mainly in the Pacific and South Atlantic, and accounted for more than 800,000 tons of Allied shipping. Unlike the Enigma system used by the U-boats, the raider code was considered by Allied Intelligence to be unbreakable.

The raiders were finally hunted to extinction by sheer weight of numbers of Allied aircraft and warships, and a wider use of Intelligence besides decryption. The effort used to sink these ships far outstripped their worth, even before their successes are taken into consideration.

Seven of the nine were sunk and two scrapped, so no examples of these interesting vessels remained at the surface. Of those sunk, all were in very deep water, or had been salvaged. The only exception was the Komet.

HSK KOMET HAD ALREADY COMPLETED a successful foray into the Pacific when she was sunk in the Channel. Her first patrol had lasted 512 days and accounted for 42,000 tons of shipping.

Remarkably, when she sailed, Russia was a German ally and Komet was escorted through the icebound northern route around Siberia into the Pacific, a rare feat for which the vessel is remembered in navigational circles to this day. However, her successes were not to last.

By the time Komet was readied for a second foray Russia was an enemy, so she had to break out into the Atlantic down the Channel. By late 1942, Allied naval power in home waters was building fast, shifting to an offensive footing and providing the capability to attack German supply shipping on the French side.

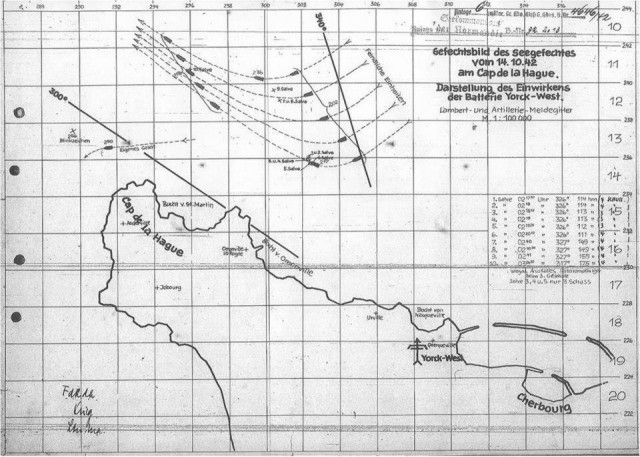

Despite the impregnable raider codes, the Allies were reading much German naval radio traffic from other sources, which hinted at an attempt to pass a major naval unit down the Channel. So, on 13 October, 1942, Operation Bowery was launched to trap and destroy the Komet.

Travelling across the Baie de Seine, Komet was sighted from a Swordfish aircraft. The Royal Navy sent 10 destroyers and a flotilla of motor torpedo boats to find and destroy her. Force A, the destroyers HMS Cottesmore, Albrighton, Quorn, Eskdale and Glaisdale and MTB 236, intercepted the convoy escorting Komet off Cap le Hague shortly after 1am on 14 October.

During the swift night action that followed, Komet was blown to pieces and sank with her entire crew of 351. The credit went to Lt R Drayson, RNVR of MTB 236.

It was his first operation in command, and he had become separated from the rest of his flotilla (a serious offence), but made his way to Cap le Hague on his own initiative and, in the middle of the raging fire-fight, sighted Komet and fired his torpedoes, scoring at least one hit. Drayson was awarded the DSC.

The violence of the explosion that tore Komet apart is unimaginable. The fireball was seen 20 miles away in the Channel Islands, and the flames shot more than 300m into the air. The nature of the destruction has caused controversy ever since.

The reports from her escort ships claimed that shellfire from the British destroyers sank her, rather than torpedoes. What is certain is that some form of secondary detonation caused the massive explosion.

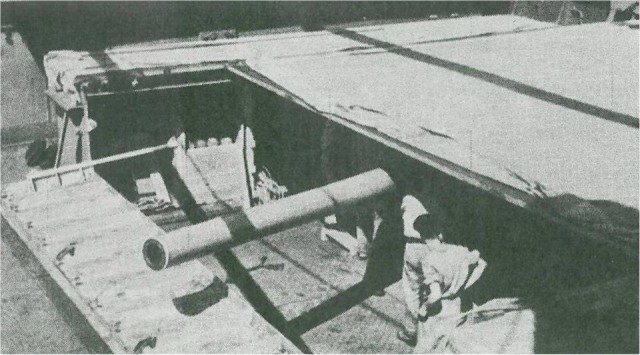

Equipped for a long patrol, Komet would have been packed with fuel for its plane and ammunition for its 155mm guns, torpedoes and mines. Having no armour belt, she was vulnerable to attack, and the potential for a magazine explosion.

THE ONLY WAY TO CONFIRM what happened to Komet was to dive the wreck. Yet when I looked into doing this in 1997, it became clear that nobody knew where the wreck lay. This was mysterious, because the Channel is well surveyed and much dived. Most of its larger wrecks were at least charted by then, if not yet dived.

Moreover, the historic position for the sinking, given in contemporary Admiralty reports, plotted the wreck in around 50m, within air-diving range. There was no point in looking for Komet until better information came my way.

I was researching shipwrecks in the Public Records Office in 2005 when I came across some eyewitness reports of the battle. They seemed to indicate that the wreck was very much landward of the Admiralty position. This gave me something to work on.

By this time I had also confided my interest in this wreck to dive operator and wreck historian Richard Keen of Guernsey. Information from him, by way of a local fisherman’s snag chart, coupled with a better insight into how the battle had developed, gave me the chance to nail this wreck.

In 2006 I chartered mv Maureen, the famous Dartmouth dive charter boat run by the equally famous Rowley family, Mike, Penny and Giles. My dive team was made up of experienced members of past trips going back several years, all up for a challenge

I reasoned that if divers had not found Komet already, there had to be a good explanation – the tide. The ripping tides around Cap Le Hague are notorious, and very difficult to judge for slack water. Who would want to dive there without very good reason?

When Maureen arrived at the site, it took us 24 hours to work out when slack water was. On the best neap tide of 2006, there was only one slack per day, and it lasted less than 15 minutes! To carry out a dive to 57-60m in a very tidal area requires planning and experience.

We deployed a ‘lazy shot’ decompression system which relies on all divers coming back up the shotline and releasing the decompression ‘lazy’ line. All the deco could then be done in comfort as we drifted downtide.

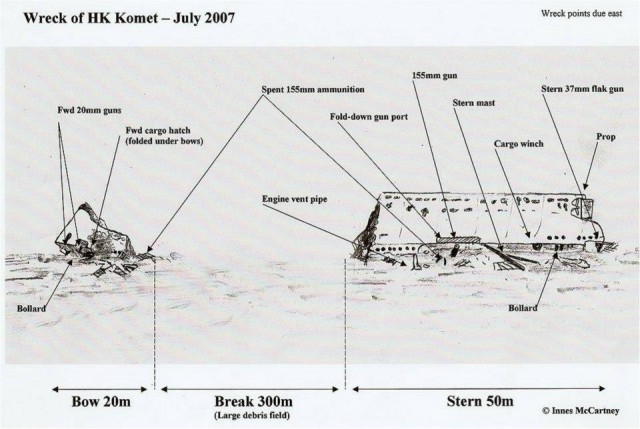

ON A FLAT, SUNNY JULY AFTERNOON we descended through green, yet clear, Channel water to the top of a wreck. It was clear that it was upside-down. The first items I recall seeing were the four-bladed propeller and rudder at the stern.

As I landed on the keel and swam down onto the starboard side of the wreck, two things struck me. Firstly, this was a virgin site, because portable items lay scattered everywhere. Even in French waters, where artefact collection is prohibited, this is a rare sight.

There was something else. There was no marine growth, no concretion on the portholes, no crud on the wreck. The answer, of course, was that the vicious tides simply polish off any growth.

A swim along Komet’s side began to reveal items that pointed to the wreck’s identity. It looked like a merchant ship, but among the debris on the seabed were fired 150mm shells, the right calibre and a rare one for the Kriegsmarine.

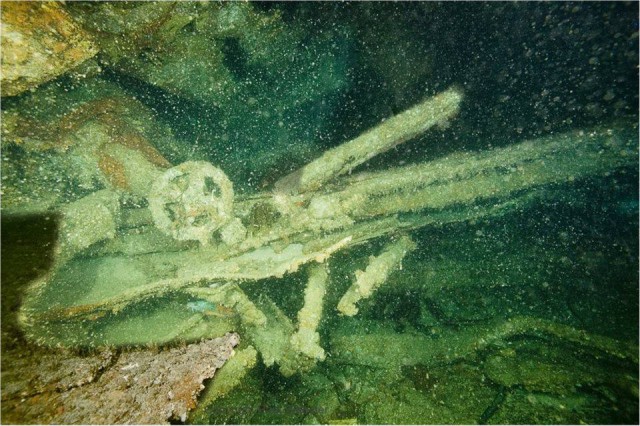

Moving forward, we came to a break in the wreck, about halfway along what we supposed to be the ship. This pointed to a major catastrophic sinking event. Finning aft with my buddy Greg Marshall, we found the stern centreline gun poking out from under the wreck.

A quick measurement of the calibre confirmed what I was thinking. My video camera was capturing what I was seeing as I swam past the gun and on toward the stern, where a flak position was seen – also correct for Komet.

In the blink of an eye, our dive time was over, the tide was picking up and we had to head for the shotline and the relative safety of a lengthy drifting decompression. Once back on Maureen, we steamed up to the wreck and looked at it on the sounder.

It was too short for Komet, yet we had seen a break. We sat down to eat, and as we tucked into good old Maureen grub, the boat drifted over what we presumed to be the other half of the wreck! And that part wasn’t on any chart.

That evening, I examined the video footage Mark Callaghan and I had filmed. I was staggered to notice that above the gun we had found was the foldaway gun-port to hide it when not in action. This meant that the wreck had to be Komet.

It was a great moment, and a relief to have finally found the wreck. But we couldn’t tarry on the French side any longer. So in 2007 I charted Maureen again and we went back for a more comprehensive view of the wreck.

BY NOW THE NEWS OF KOMET’S DISCOVERY had begun to drift out and, as is always the case, more information about the ship begun to surface. Over four days we dived both halves of the wreck, and were able to get a good idea of what was there.

The stern section was around 50m long, upside-down and listing to port. The break was right in the area of the bridge, and fairly clean. Little debris could be seen on the seabed around it. Yet 300m due east lay the bows, which were very different.

The bow section was also upside-down, but much the more damaged. It took me two dives to work out what was there. When I located the two forward flak guns, I was astonished to find decking above and below them.

I followed the line of the deck and worked out that the entire forward section had been bent back on itself by the force of the explosion that sank the ship. The forward section was smaller, with perhaps only 20m there. Some 40m of the ship had gone entirely!

To confirm this, Mark and Greg swam a line off the bows toward the stern, and confirmed that there was little recognisable wreckage between the two halves. Whatever was there had been blown to pieces. This discovery was remarkable.

I’ve seen blasted warships at Jutland, ships that suffered catastrophic explosions, but they had not disintegrated in this way. They were armoured ships of war – Komet was a merchant ship, equipped as a cruiser, but with not nearly the same degree of strength.

The ultimate reward for closing off the Komet story was to know where 351 sailors had died on an awful night in 1942. As the only example of an armed merchant raider in the world, this wreck is a rare, important and exciting dive.

This major sea-grave is protected by being in French waters and is unlikely to suffer the predations of commercial salvage, as the Jutland wrecks have. Earlier this year I was able to relate the Komet story to audiences in Germany, which remains its spiritual home.

The other divers were Phil Grigg, Robert Van Der Meer, Sarah Jepson, John Cobb, Jim McCinnes, Patricia McCartney, Mark Callaghan, Greg ‘Badger’ Marshall and Paul Webster.

In the sandbank Phil Grigg found these Kriegsmarine pattern plates, further evidence we had found Komet (Phil Grigg)

The one seriously niggling question I have is why the wreck points to the east? No witness accounts state that Komet turned back for Cherbourg. It is a real mystery.

The starboard side was not flat down on the seabed. The entire area is festooned with small debris. A sure sign no one has been here before (Innes McCartney).

The Komet Team 2006 Giles, Phil, Robert, Me, Sarah, John, Jim, Penny, Mike, Trish, Mark and Greg. Paul joined us in 2007. Komet was a great project with an excellent team.

You can follow Innes on Facebook, Twitter and you can buy many of his books via Amazon

Dr. Innes McCartney – Nautical Archaeologist, Naval Historian and 26 years a Wreck Diver.