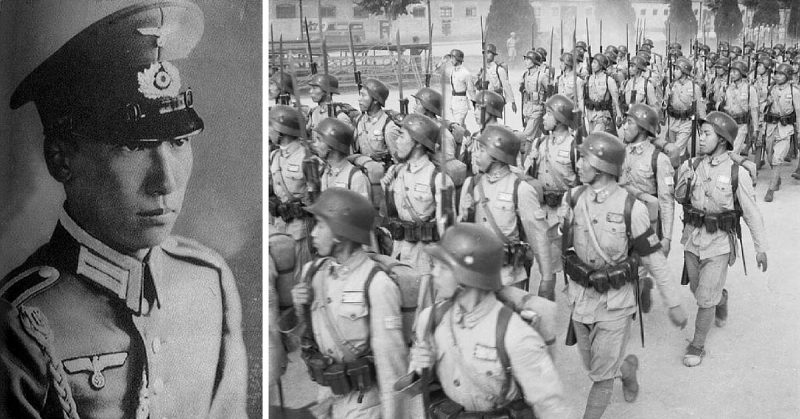

Look at these photos – a Nazi German officer and Wehrmacht troops, right? Wrong.

A quick first glance at these photos would have most military history enthusiasts fooled. You would be forgiven to assume that these are German-trained Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) personnel. But that could not be further from the truth – they are in fact Nazi-trained Chinese soldiers of the National Revolutionary Army (NRA), destined to fight Japanese invaders. The Wehrmacht officer is Chiang Wei-Kuo, adopted son of Chinese Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek. Chiang Wei-Kuo commanded a German Panzer during Anschluss, earned a commission as a Wehrmacht lieutenant in anticipation of Fall Weiss, before being recalled back to China.

How is it that the son of a WWII Allied Power’s head of state served on the wrong side on the road to war, you ask?

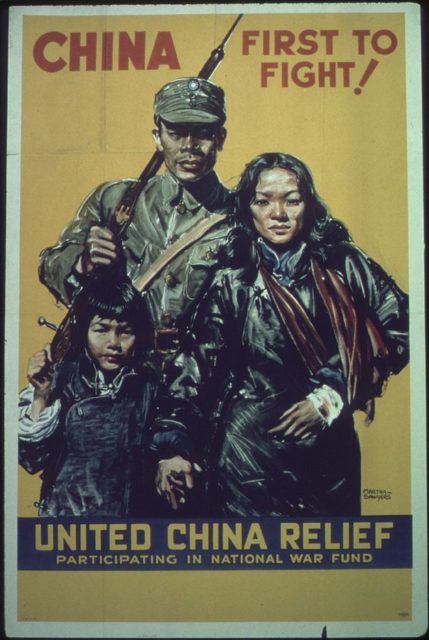

We all know that China was the ‘first to fight’ Imperial Japan, first in 1931, when Manchuria was annexed to form Japan’s Manchukuo puppet, only to be followed by full-scale invasion in 1937. Facing a far superior enemy both technologically and organisationally, backed by an industrialized war economy, China naturally sought foreign military assistance from any willing partners. Ironically, one of these partners was Nazi Germany, Japan’s soon-to-be ally.

Nazi support was motivated by two reasons: the economic need for China’s raw materials, and the anti-communism of Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist Party, or Kuomintang (KMT). Most surprisingly, Hitler’s personal view that ‘I have never regarded the Chinese or the Japanese as being inferior to ourselves’ also excluded the Chinese from Nazi racial antagonism in foreign relations.

This unexpected partnership between Germany and the KMT actually predated Hitler’s rise to power in 1933. After China’s Beiyang Government declared war on Imperial Germany in 1917, Sino-German cooperation was established upon German defeat. As China never actually fought against Germany (Chinese manpower contributions to the Allies were through the Chinese Labour Corps), coupled with the fact that Weimar Germany renounced all territorial claims in China, the renewed partnership emerged from WWI largely unscathed.

With the signing of the Sino-German peace treaty in 1921, the groundwork was laid for cooperation: China offered access to badly-needed raw materials for post-war German reconstruction, whereas Weimar Germany offered modern military hardware and advice for a threatened China.

In the lucrative market of the warlord-ridden Chinese civil war, Germany had an edge. Unlike the KMT’s other major foreign supporter before Pearl Harbour, the USSR, Weimar Germany had no political agenda. While the Soviets used military assistance to leverage for the inclusion of their Chinese Communist Party (CCP) comrades within KMT politics, the Germans were initially interested in business and anti-communism, having been crippled of any ability or will to impose imperial designs on China.

Through German-educated KMT officials like Chu Chia-Hua, soldiers of fortune like Max Bauer were recruited to China as individuals during the Weimar years, avoiding treaty prohibition of Germany’s foreign military investments. Mostly officers from WWI sharing the anti-communist sentiments of the right-wing KMT faction led by Chiang Kai-shek (Bauer was personally involved in the Kapp Putsch), they were more than happy to advise the KMT.

The famed Whampoa Military Academy, China’s equivalent of Sandhurst/West Point, was significantly strengthened in the late 1920s by the military intelligence and training expertise of 20 odd German officers recruited by Bauer. Infrastructure development under the KMT also took place under German industrial guidance. This personnel presence was coupled with clandestine German arms exports, which amounted to over 50% of China’s arms imports in 1925 while WWI victors excluded Germany in their 1919 arms embargo against China.

Upon Nazi victory in Germany’s 1933 elections and Hitler’s subsequent seizure of power, Sino-German ties strengthened with the removal of Weimar neutrality obligations. On Chiang’s invitation, the fanatical Hitlerjugend even visited China (see photo).

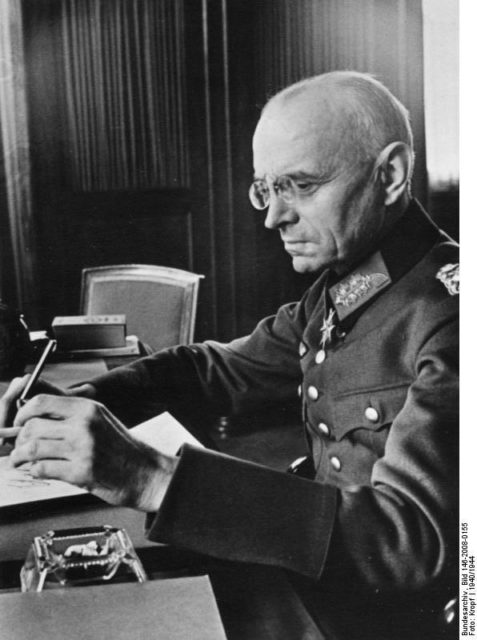

Hans von Seeckt, the general responsible for Marshal von Mackensen’s Eastern Front victories, was sent to advise Chiang on his fight against the CCP. His ‘80 Division Plan’ was key in advocating a small, highly centralized, mobile and well-equipped modernized force, contrary to most contemporary Chinese factional armies. Implementing German ideas such as forming elite-heer training brigades and eliminating regionalism between different divisions, von Seeckt’s methods partially materialised in the KMT’s eight German-trained elite divisions (80,000 men), including the famed 88th, who were destined to pose the fiercest resistance against the IJA at the famed defence of Shanghai’s Sihang Warehouse.

Alexander von Falkenhausen, the newly-retired head of the Dresden Infantry School, took charge of implementing von Seeckt’s plan. Von Falkenhausen scaled down von Seeckt’s ambitious vision to fit China’s limited industrial capacity, which according to von Seeckt was approximately 80% obsolete by the 1930s for modern military manufacturing. Instead of 80 full divisions, von Falkenhausen pushed for building enough capabilities for a small mobile force specialised in small-arms tactics, akin to late-WWI Sturmtruppen, tasked with infiltration. All the while, weapons modernization was accelerated.

The established Hanyang Arsenal overhauled to produce Maxim guns for much-needed automatic fire support, as well as the Type 24 Chiang Kai-shek Rifle (a copy of the Mauser M1924, the ancestor to the Karabiner 98k), while new factories were set up to manufacture German-designed modern equipment, including the MG-34 and even parts for the few armoured cars China bought from the Reich. Imported arms, including the iconic M35 helmets and Mauser C96 ‘Broomhandle’ automatic handguns as well as Rheinmetall and Krupp-manufactured artillery, were ordered in vast quantities to supplement the nascent local production.

Von Falkenhausen advised Chiang to wage a war of attrition against the Japanese, slowly retreating from northern China and to refrain from attacking north of the Yellow River line. He advocated for infiltrating guerrilla tactics to complement this defence-in-depth approach, making the Japanese pay for each advance they make. Sure enough, Chiang listened, and Japanese progress was slowed for months in the lead-up to the fall of Nanjing, enabling the KMT government to move its manpower and war industry into the Sichuan interior.

Most importantly, the successful delaying actions at the Second Battle of Shanghai, and the Battle of Nanjing finally proved the NRA a match to the technologically and organisationally advanced Japanese. The admirable last stand at Shanghai for 76 days, despite heavy casualties, boosted Chinese morale to carry on the fight, leading to the famous victories at Tai’erzhuang in 1938, against Japanese armour-supported infantry, and at Suixian–Zaoyang in 1939, long before the Western Allies’ first victories or even the outbreak of European war.

So Chiang Kai-shek’s decision to send Wei-Kuo to learn from the Wehrmacht should come as no surprise. In fact, Chiang’s personal ties to Germany was so widespread that, even after the 1937 outbreak of Sino-Japanese war, a significant Chinese lobby remained in Berlin, calling for a resumption of full Nazi-China ties despite the Sino-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact.

When they were finally recalled, von Falkenhausen and his fellow German advisors promised not to share any information on Chinese war plans with their new Japanese allies. When the 1941 Tripartite Pact formalized the Germany-Italy-Japan Axis, German assistance to China completely terminated, but the military foundations that the partnership had already laid contributed to the eventual Chinese victory.

Von Falkenhausen, for his part, kept his word and continued writing to Chiang, exchanging gifts until long after the war ended.

About the Author

Norton Yeung is a current final year undergraduate student of Politics and International Relations at the University of Bath, United Kingdom. Norton has a lifetime interest in military history, having volunteered as a researcher at the Museum of Coastal Defence in his native Hong Kong. As a grandson of a WWII/Chinese Civil War veteran, his primary area of interest is the China Burma India (CBI) and Pacific theaters of WWII.

He currently serves as Editorial Assistant for Bandung: Journal of the Global South, a Springer Open Access academic journal on the politics, culture and international relations of developing countries.