War History Online presents this Guest Article by James Lyon

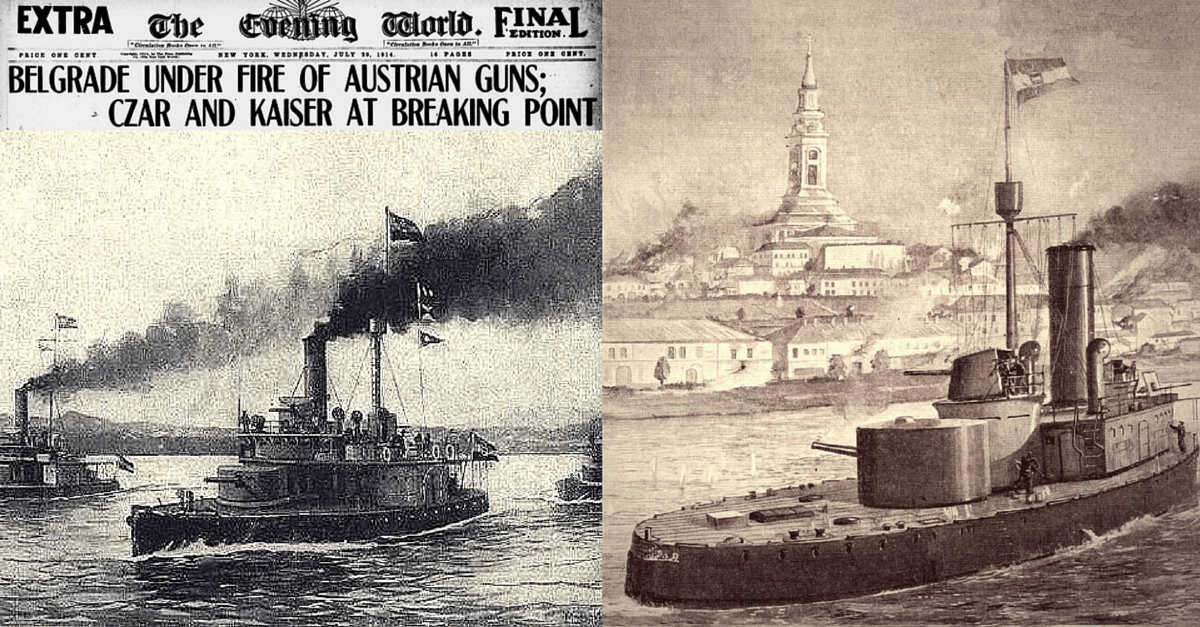

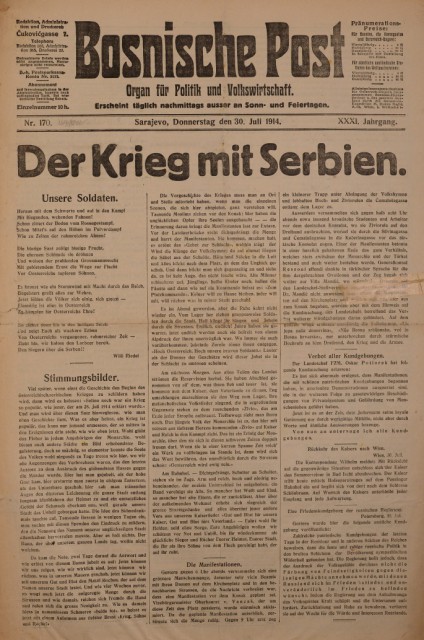

Most people think the first battle of World War One took place on 5 August 1914, when Germany invaded Belgium. The first fighting, however, occurred nine days earlier on the night of 28 July, mere hours after Austria-Hungary’s declaration of war against Serbia. This battle was an amphibious assault meant to capture the Serbian capital of Belgrade.

The Austro-Hungarian declaration of war arrived in Serbia via open telegram around noon on 28 July, and all of Belgrade soon knew its contents. Shops closed as people rushed to hoard food and supplies. Rumors that the city’s water supply would be turned off prompted crowds to form around the many public fountains. The Chief of the General Staff, Vojvoda Radomir Putnik, was at a spa in Austria-Hungary with the key to the safe holding Serbia’s mobilization plans; the safe had to be dynamited open.

The Serbian army began to evacuate Belgrade on 25 July, the day the Austro-Hungarian ultimatum expired. Crates of gold bars from the National Bank were escorted by armed military cadets to the railway station and loaded on a special train.

The military garrison evacuated the Kalemegdan fortress at the confluence of the Sava and Danube Rivers and emptied all ammunition depots. Hospital units left the city, heading south. Diplomatic missions packed in anticipation of the capital moving to Niš. Serbia’s government evacuated its offices and messengers raced to and from the Military Ministry.

All soldiers, artillery, and stocks of ammunition were withdrawn from the massive Kalemegdan fortress. Given the time necessary for Austria-Hungary to concentrate troops, Military Minister Dušan Stefanović believed hostilities wouldn’t start until 4 August at the earliest. Therefore, a decision to defend the capital could wait. Belgrade was difficult to defend, located on a hill at the confluence of the Sava and Danube Rivers, with just a few hundred meters of water separating it from Austria-Hungary.

The Danube I Division was responsible for defending Belgrade and had concentrated most of its forces to the west of the city on Banovo Hill or at Banjica to the south of the city. As of late in the evening on 28 July, neither the High Command nor Danube I commander Colonel Milovoje Anđelković had decided to defend Belgrade. In the meantime, there were no artillery or machine guns in place, and the city was guarded only by an unorganized group of Gendarmes, customs police, a few irregular Četniks from Vojislav Tankosić’s Detachment, a company from the 18th Infantry Regiment, and members of a gymnastic society. The city was ripe for the taking.

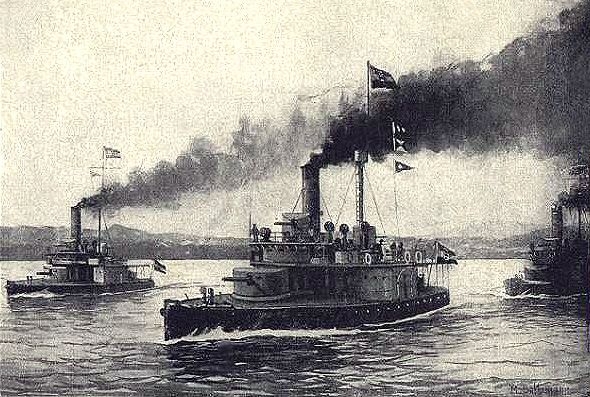

At approximately 23:30 on the night of 28 July, rifle fire erupted along the Serbian side of the Sava River. It began near the Kalemegdan fortress’ river wall, and then moved upstream towards the Sava landing. Loud cannon fire and explosions followed along the Serbian side of the river. The financial police and Gendarmes ran along the river bank, shooting at dark shapes on the water. Three Austro-Hungarian tugs pulling barges with infantry had tried to land near the lower fortress of the Kalemegdan, but veered away after coming under intense rifle fire. The barges were escorted by a heavily armored river monitor, which began shelling the Kalemegdan and the city with its 120-mm guns.

The move was brilliant. If the amphibious landing succeeded, Vienna would capture Serbia’s capital city and present the other Great Powers with a fait accompli before their mobilizations were complete. Vienna could claim satisfaction for the Sarajevo assassination, and Habsburg leverage would increase at any peace conference. Possibly a general European war could have been prevented. It could also give the wavering neutral countries – Bulgaria, Greece, and Romania in particular – cause to ally with Austria-Hungary against Serbia and Russia in exchange for territorial concessions. It might also dissuade France from keeping its commitments to Russia and demonstrate St. Petersburg was incapable of protecting Serbia. Millions of lives and the fate of empires and countries rested on this midnight operation.

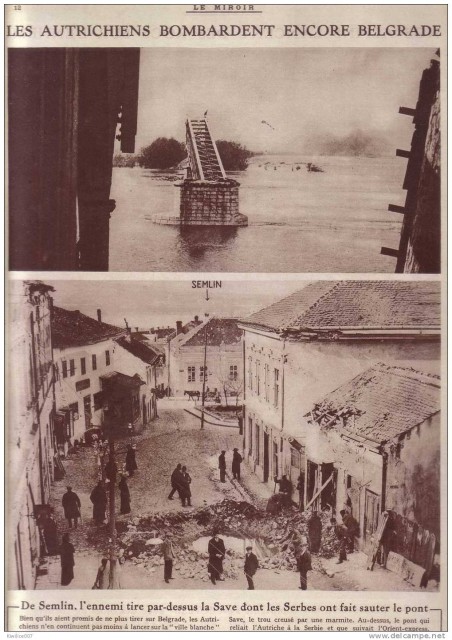

As the first tug and its barges veered away from the river wall, they headed up the Sava River towards the railway bridge, with the financial police and gendarmes in hot pursuit on foot. The monitor stayed near Kalemegdan and continued shelling the city and fortress. As the tug approached the railway bridge, by now early on the morning of 29 July, the Serbs encountered small arms fire from the Austro-Hungarian side of the bridge. Fearing that Habsburg forces would cross the bridge, the Tankosić Detachment dynamited the span nearest the Serbian shore shortly after 01:00, cutting Serbia’s only bridge with Europe. Under fierce small arms fire, one tug ran aground on the Austro-Hungarian side of the river. The troops in the barges were sitting ducks. Panicked soldiers dove overboard from the barges; some swam to the north bank of the Sava. Others drowned. At 01:10, a telephone operator reported that the fighting had stopped.

At first light on the morning of 29 July, one steam tug and eight empty barges were visible, aground under the Habsburg side of the ruined railroad bridge. A second tug with a string of barges had run aground across from the Sava landing, at Ušće, near modern Belgrade’s Old Fairground. The third tug returned safely to Zemun with its barges. The chief of the hospital in Zemun, Dr. Sava Nedeljković, a Serb, reported heavy Habsburg casualties that filled the hospital’s 100 beds and forced the wounded to be lodged in private homes or lie in the streets. The Zemun police force went door to door on the morning of 29 July, collecting bedding for the wounded.

In this brief battle, the first of the Great War, the first Serb to die was Dušan Ðonović, a student at the Commercial Academy and a member of Jovan Babunski’s Četnik group. Rifle fire from the Serbian defenders killed the captain of the first tug, Karl Eberling, and his helmsman, Mikhail Gemsberger, the first Austro-Hungarian casualties of the war.

James Lyon is author of Serbia and the Balkan Front, 1914: The Outbreak of the Great War (Bloomsbury Academic, 2015). He has a Ph.D. in Balkan History, is founder of the Foundation for the Preservation of Historical Heritage, and an Associate Researcher at the University of Graz.

All photos provided by the author.