War History online proudly presents this Guest Piece from Jeremy P. Ämick, who is a military historian and writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.

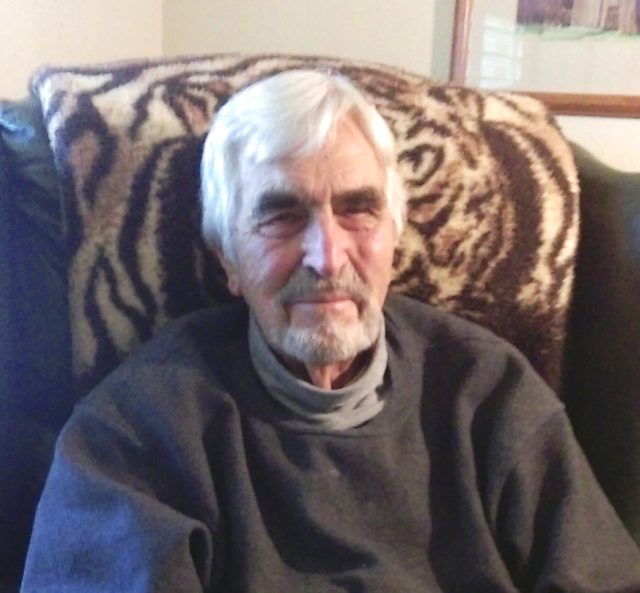

All too often, veterans of WWII describe their service in a manner that moderates the importance of the contributions they have made, dismissing any notion of heroism or stellar performance. Though he admits that he is proud of his service as a pilot during the war, Jefferson City, Mo., veteran Charlie Palmer chose to summarize his own military experience with the simple, straightforward assertion, “I did my bit, what I was trained to do.”

Born in Plainfield, N.J., in 1924, Palmer explained that the majority of his early years were spent living with his sister and her husband since his father died when he was a child and his mother was in failing health.

He went on to graduate from high school in 1942 and, during the heart of World War II, made the decision to take the Air Corps exam “because I wanted to be a pilot,” he affirmed.

“There really is no easy answer as to why, but the best way that I can explain it is that I just liked the idea of flying; I liked airplanes and my heart always seemed to be set on that notion,” he said.

After passing the battery of required military exams and physicals, the aspiring aviator officially entered service at the induction center at Fort Dix, N.J., followed by his transfer to the Air Corps Training Command in San Antonio, Texas. It was here, the veteran explained, that he underwent additional testing to determine his suitability for service as a pilot, bombardier or navigator.

“I passed all of the tests and qualified for pilot,” Palmer recalled. “That’s when I started several weeks of pre-flight training and we began to receive instruction in subjects such as math, Morse code, aircraft recognition and map reading.”

He continued, “Then they sent me to an airfield in Muskogee, Okla., for several weeks of primary flight training. That’s where I learned to fly a Fairchild PT-19, which was a twin-seat plane with an open cockpit.”

Soloing on this first aircraft after eight hours of instruction, the aspiring pilot’s training progressed when he was transferred to Greenville, Texas, for basic flight training in the Vultee BT-13, learning more advanced techniques including formation flying, cross country and night flying.

He progressed to twin-engine training in Houston, Texas, where he earned his wings and was commissioned a second lieutenant. For the next several months, he continued his training aboard additional types of aircraft at several airfields throughout Texas. Eventually, he received assignment to Barksdale Field near Austin, where he refined his aviation skills aboard a Douglas C-47 military transport aircraft.

“Basically, I spent most of my time in the United States training at several different locations for about six to eight weeks at a time,” Palmer said. “I then went overseas from Alliance, Neb., to Chalgrove Field in Oxfordshire, England in December 1944.”

As Palmer explained, he was assigned to a Pathfinder unit. This duty, he further noted, required the pilots to take off when visibility was limited, fly a mission that included dropping resupplies or paratroopers, and then returning to their home base, all of this under instrument conditions.

This overseas assignment also resulted in their aircraft flying supply missions during which Palmer helped deliver hundreds of five-gallon cans of gasoline for the assorted vehicles and tanks that General Patton’s Third Army used in its relentless push across Southern Germany.

“One mission that I distinctly remember flying was with the 15th Airborne Division and named ‘Operation Varsity,’” he said. “We flew a couple of minutes past the Rhine near Wesel, Germany and dropped paratroopers to reinforce the British troops that were already there and then returned to base.”

He added, “There were other groups that had to fly further on to make their drops.” Pausing, he solemnly concluded, “They were getting shot up something terrible. I thought for sure that I was going to get hit on that mission, but we all made it back.”

Following the war’s end in May 1945, Palmer flew several non-combat missions before returning to the United States in early June 1945. He completed the remainder of his service as a C-47 instructor in Battle Creek, Mich., training new pilots until receiving his discharge on December 5, 1945.

The former aviator went on to attend college at the University of Newark (now Rutgers University), earning his bachelor’s degree in business administration. In the ensuing years, he pursued a sales career path, which included working for such companies as Warner Lambert, Monsanto, and Bank Building in St. Louis, 7-Up in Clayton and later as an independent training consultant.

He and his wife have resided in Jefferson City for many years, where he has remained active in the community by volunteering with the Lewis and Clark Task Force (serving seven years as the organization’s chairman), JC Parks and Recreation and Missouri Archives.

The veteran affirms that when reflecting on his service, he does not view himself as having done anything “special” during the war, instead he chooses to lavish credit on his fellow soldiers and aviators who did not make it home. However, he recognizes that the brief time he spent as a military pilot did teach him the significance of preparation.

“There were always things that we had to learn so that all of us would be ready,” Palmer noted. “During the training, I never felt like we were being rushed through; I could tell that they wanted us to be prepared for whatever we might face.

“That’s demonstrated when I lost an engine on a takeoff and landed safely. You had to master your aircraft and if you weren’t prepared, you had a problem. To that end,” he affirmed, “I am proud to say that I was a pilot—there’s no question about that!”