War History Online proudly presents this Guest Article from Annette Oppenlander.

When we examine the history of WWII, we often focus on the myriad of battles that took place around the world, the thousands of soldiers dying on a daily basis, the carnage on the beaches of Normandy. We also examine the horrific toll Hitler’s evil took on the Jews and other minorities.

What we rarely look at are the civilians of WWII, in particular, war children. The reason this subject is dear to my heart is that my own parents were such children, growing up in Germany in the Third Reich. My mother was seven years old when her father left for the war, my father eleven.

Of course, growing up in Germany myself didn’t exactly interest me in their history—until I moved to the U.S. The unique perspective of seeing Germany’s history from a distance and my personal connection to its past were motivation to interview my parents about their experience as war children. That was in 2002 and kicked off a series of short stories. At the time I was a beginning writer and it took until 2009 to develop a coherent story. So I thought.

But how do you capture the emotional toll it took on my mother to see her father leave for the war, to be neglected by her mother in favor of her younger brother, to be left to her own devices dealing with a molesting neighbor and the ever-increasing threat of bombs? How do you describe a young boy’s struggle to take care of his family amidst ever-dwindling rations, butchering a warhorse at the age of 15 and dealing with the fallout from a destroyed nation?

Not easily. Not quickly. It took another eight years to shape the novel into the story it needed to be. It took dozens of rewrites, edits or how the cliché says, ‘blood, sweat, and tears.’ Well, maybe not blood, but definitely sweat and tears.

We rarely consider what it took to survive in the later war years as a civilian, especially a child/youth. There was hardly any food, in the last year pretty much none. Every family had ration cards, but those cards bought nothing because the stores were empty. People froze because there was no coal. That didn’t stop Hitler from completely destroying the country. He never even considered giving up. In fact, he said that if he/Germany couldn’t win the war, then Germans had no business living past it. He himself made good on that promise by committing suicide on April 30, 1945, eight days before the unconditional surrender of Germany.

By then the war was over for my parents. In March of 1945, Hitler had executed his last propaganda campaign, the People’s Storm, sending all 15- and 16-year old boys to defend the fatherland. They had no weapons and no training, and faced fully trained and equipped Russian and American soldiers. They didn’t stand a chance.

My father was one of those 16-year old boys. Except he and his best friend decided to hide in the woods and wait out the war. Of course, they didn’t know how long it would last. And being caught meant certain execution. As late as early April they ran into fanatical SS troops who planned to take the boys to their destination. My father and his friend escaped in the night. When they returned for a secret home visit, they learned that the war in their hometown, Solingen, was over. The Americans had moved in without a fight on April 18/19. The civilian population was relieved.

And so most of us assume that the war ended and everything returned back to normal. Not for Germany. Every city of size had been destroyed by at least 50 percent. There was no infrastructure, no food, no coal, no light bulbs, nails, windowpanes, clothes or paper. The British and U.S. occupation struggled to create new ration systems. Even today you can read online that German citizens received 1,500 daily calories. Not true. My parents, at that point 13 and 16 years old, continued to starve.

They had ration cards, but the stores remained empty. And as men—former soldiers and POWs—trickled back into towns, and the women began the cleanup of the cities, the Reichsmark, the German currency, spiraled into runaway inflation. Black markets sprang up, families traveled to the countryside to barter their last valuables for food while British, American, French and Russian Allies tried to figure out how to administer a torn-apart country.

Starvation and mayhem continued until June 1948 when the new German currency, the Deutsche Mark was introduced. On June 19, the stores still had signs in the windows reading… “out of stock, closed for construction.” The morning of June 20, every imaginable product lay on display in shop windows: chocolate, fancy shoes, cameras, stockings, dresses, liquor.

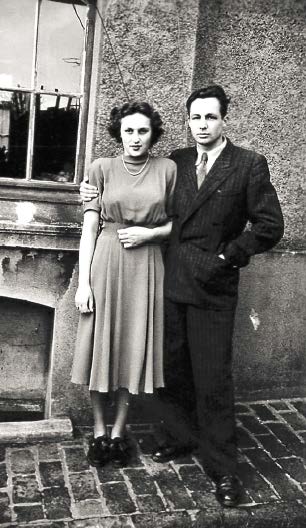

That was three years after the war and my parents had pretty much starved for six years. They met in 1949 at a little country fair and fell in love. At first, their relationship seemed like any other. But old wounds and secrets had a way of rising to the surface once more.

My mother’s father was still a POW in a Russian gulag. The French, British and American Allies had long released their prisoners. Russia’s dictator, Stalin, loved building new gulags in Siberia and the Ural. My father grappled with the guilt of surviving when all the boys from his class had never returned after the People’s Storm.

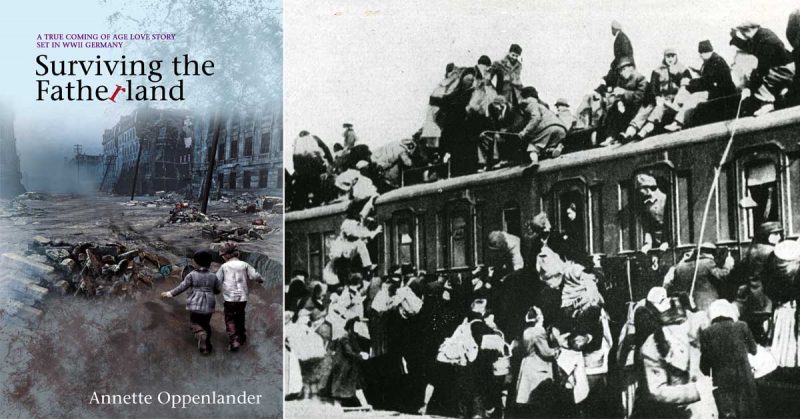

Thankfully, the story ends happily because I’m proof. And after 15 years and endless tribulations, workshops and four other published novels, I was able to tell my parents’ story the way it needed to be told. The fact, Surviving the Fatherland, was a winner of the 2017 National Indie Excellence Award and inducted into the Hall of Fame by International Writers Inspiring Change is a testament that it was worth the wait. And the sweat and tears.

Annette Oppenlander Website.

All photos provided by the author.