War History Online proudly presents this Guest Article by military historian Jeremy P. Amick.

“Seventy-something years ago,” described Eldon, Mo., veteran James Belshe, a “wide-eyed young man still in high school tried to enlist in the Army Air Forces with dreams of someday becoming a pilot.” When he was told he was colorblind and ineligible to pursue a military aviation career, he returned to his high school studies.

“That’s when I got drafted by the Army,” Belshe grinned. “I graduated (from Eldon High School) in May 1943 and a few days later I was at Jefferson Barracks being inducted into the Army.”

After only a few days at the St. Louis area post, the new recruit traveled to Camp Roberts, Calif., spending the next few weeks in basic infantry training followed by instruction as a “field lineman,” as is noted on his discharge papers.

“They decided that I would go into communications,” Belshe recalled. “We learned Morse code, semaphore (communication using flags), radios, telephones … anything that was used to communicate somehow.”

When his training ended in late summer 1943, he returned home for two weeks of leave and then traveled to California to board the New Amsterdam (a Dutch luxury liner converted to a troop ship). The ship sailed for New Zealand where Belshe was assigned to the headquarters company for the 161st Infantry Regiment of the 25th Infantry Division (ID).

As Belshe explained, the 25th ID had already participated in several major engagements and encountered fierce resistance from well-organized Japanese forces on Guadalcanal followed by operations in the Solomon Islands. Having encountered significant casualties, the division moved to New Zealand toward the latter part of 1943 to recuperate and take on replacements such as Belshe.

“I really enjoyed my time at New Zealand,” Belshe affirmed. “That’s when the division was on leave, which meant that I was too.” He added, “We had a big stock tank full of beer (in the middle of the camp) and you could go to town anytime you wanted. I thought to myself, ‘This isn’t so bad.’”

The soldier discovered that his pleasant duty conditions were temporary when, in early 1944, the division moved to an “area in the woods” in New Caledonia—a French territory comprised of islands in the South Pacific.

“I worked on the switchboard so I knew what was going on around the place,” said the former soldier. “We also strung telephone lines all over our area of operations.”

The men of the division were soon informed that they would become part of the invasion of the Philippines and, in November 1944, began practicing assault landings followed by a journey aboard landing ship tanks (LSTs) to Lingayen Gulf several weeks later.

Upon landing, Belshe recalls, there was not any notable resistance since the “Alamo Scouts (recon unit of the U.S. Army) and Fiji Scouts had pretty well taken care of everything,” but the division’s push inland on the island of Luzon introduced the young soldier to ever-present threats existent in all areas of a warzone.

“The island (Luzon) was pretty well cut in two by us and other divisions,” said Belshe. “Some divisions pushed south (from the middle of the island) and we pushed north. From shortly after we arrived,” he added, “it basically became a running battle across the island.”

Continuing his assignment in the headquarters section, Belshe explained that his duties in communications kept him several miles behind heavy enemy action; however, on March 11, 1945, his distance from the front lines did not diminish his exposure to Japanese soldiers.

“Two fellows and myself decided we would walk to the (tent) to get us some chow,” he said. “We were walking down this little path and KABOOM!—that’s all that I remember.”

What Belshe later discovered is that despite the dozens of American soldiers that had secured their area of operations, a Japanese soldier managed to conceal himself along the path, shrouded by heavy brush and bushes. When Belshe and his fellow soldiers passed by the hidden enemy soldier, a grenade was rolled toward them.

“I was in the lead and was hit with shrapnel from the waist down,” he said. “The guy behind me was hit in the head and killed,” he solemnly added. “I don’t know what happened to the third guy.”

Immediately following the explosion, the Japanese soldier, now exposed, was quickly “taken care of” by machine gunners in the area. Belshe was evacuated and eventually sent to the United States for treatment, and recovered at an Army hospital at Santa Fe, New Mexico.

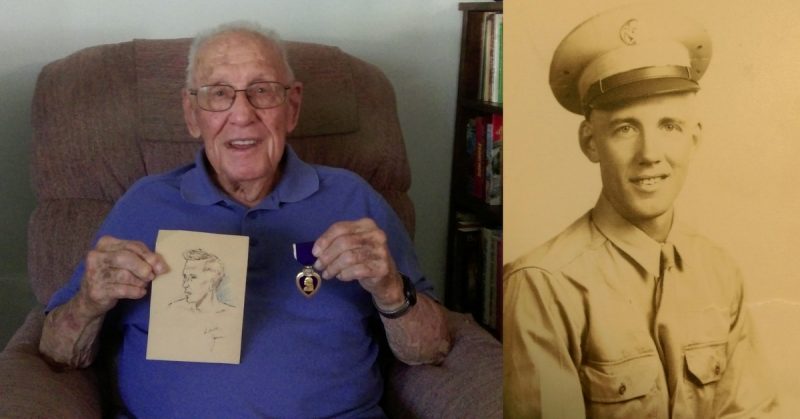

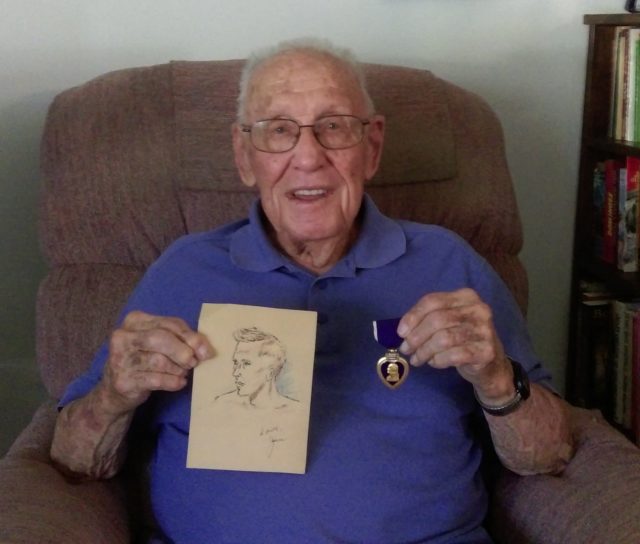

On November 23, 1945, the Purple Heart recipient received his discharge from the Army and was sent back home to Eldon, still carrying bits of shrapnel inside his body that could not be removed.

In the years following his wartime serve, Belshe married, raised three children and used his G.I. Bill benefits to earn an education degree while attending college in Warrensburg. He went on to retire after teaching for 21 years at a school in Raytown, Mo.

Though his time spent in a military uniform was filled with a combination of both memorable and stressful moments, the veteran maintains his experience overseas has been something he never shared with others, until recently.

“Honestly, I have never talked to anyone about any of this,” Belshe said, describing his time in the Army. “For me, that was always then and this is now and it just became something that I never shared.

“But there aren’t a lot of us (World War II veterans) left and I figure there are probably some people that would like to know what we went through.” Smiling, he added, “And I’m sure there’s a lot more to my story but after seventy years or so, you tend to forget a little of it.”