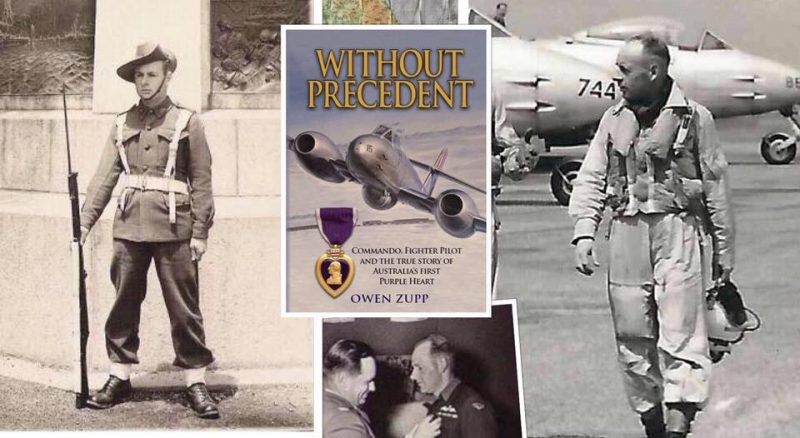

War History Online Presents This Article By Guest Blogger Owen Zupp

The frozen Korean peninsula was a hostile environment for any downed pilot in 1952. It was a situation that was exacerbated by the nearby North Korean troops for Flight Lieutenant John ‘Butch’ Hannan of the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) who had been forced to eject when his Gloster Meteor F.8 jet had been crippled by enemy fire.

As his squadron mates desperately tried to locate Hannan, one pilot caught a fleeting glance of something on the snow. Sergeant Phillip Zupp, a country boy from Australia, wheeled his jet around at low level, believing he had possibly seen Butch’s scarlet ‘marker scarf’.

Shortly after, his own world erupted as ground fire shattered his canopy and sent fragments of metal and Perspex into his face.

Zupp regained control of his aircraft at a perilously low altitude and made for the heavens, bleeding, his goggles shattered and his oxygen mask pulled askew across his face.

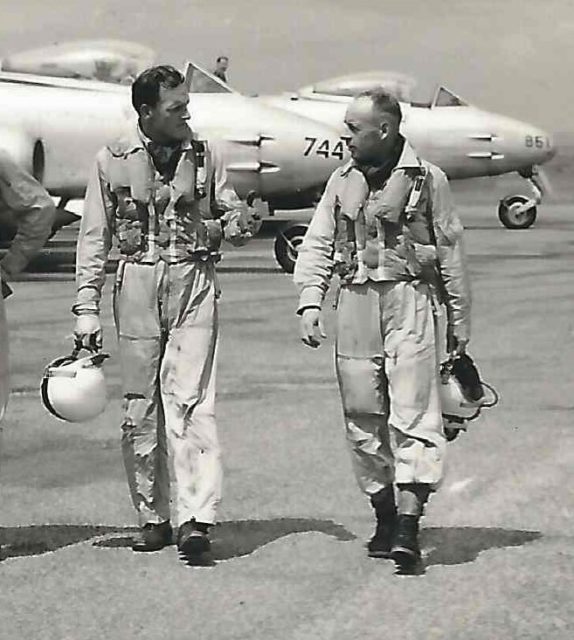

On his return to his base at K-14 Kimpo, the sight of the jet ‘with its top down’ and the wounded pilot caught the attention of a good many, including his USAF comrades-in-arms who nominated him for a distinctly American decoration – the Purple Heart.

Unknown to the young fighter pilot, that medal was to become the center of communiques between governments around the world that would reach into the 21st Century. Still, the Korean War was not the first conflict Phillip Zupp had served in.

Born into a farming family and the living through the tough times of drought and the Great Depression, Phillip Zupp could only ever dream of flying.

Forced to leave school before completing his education to assist his family, the outbreak of World War Two curiously offered the youngster a chance at flight. Initially he trained as a navigator, only to be told that he was surplus to requirements in 1944 and would not serve actively.

Offered a discharge from the air force, training in an alternate role or a transfer to another branch of the armed forces, he opted for the latter.

Joining the army, he was identified during his initial training for the specialist role of ‘commando’ and soon found himself undergoing even more intensive jungle training. As the war drew to a close in 1945, Zupp saw active service in the Pacific near Wewak in New Guinea at the age of nineteen.

The final pockets of Japanese resistance made raids upon the commando’s camp at night and attempted to ambush their patrols by day. During this time, Zupp lost two of his friends to one such ambush, only to discover their bodies on a subsequent patrol.

At the cessation of hostilities Trooper Phillip Zupp made his way by ship to Japan as one of the first contingents of the British Commonwealth Occupation Forces (BCOF). Serving in Hiroshima and Tokyo he witnessed first-hand the aftermath of the bombing, both atomic and conventional, that Japan had been subjected to.

On returning to Australia in 1947, it was not long before he enlisted in the RAAF for a second time, now as an aircraft mechanic. Learning to fly privately, Zupp was selected for pilot training at the outbreak of war in Korea, despite his lack of formal education.

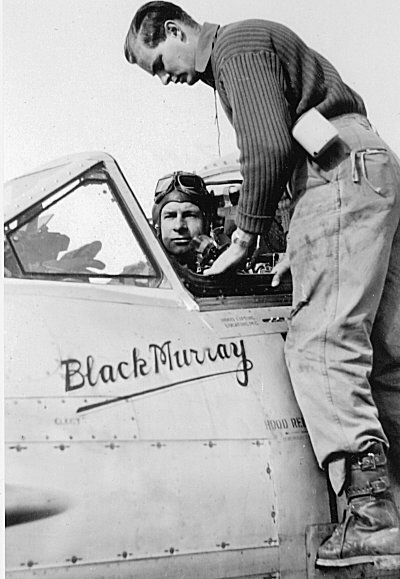

He graduated from pilot training in February 1951 and after further training on Mustang fighters and deHavilland Vampire jets, he shipped out for Japan. He spent a short period in Japan being trained of the Gloster Meteor F.8 twin-engined fighter jet before being posted to his new base at K-14 Kimpo in Korea with 77 Squadron RAAF.

By this stage, he had accumulated 400 hours total flying time, but only around eight hours on the Meteor before entering combat. The British jet did not lend itself to aerial combat at altitude with the nimble, swept wing Mig-15 and was far better suited to the demands of ground attack.

The durability of the British jet was to hold it in good stead against the ever-present ground fire, although the exposed, belly-mounted fuel tank was possibly jet’s weakest component in its new role. Offensively, the Meteor was armed with 4 x 20mm nose-mounted Hispano cannons and up to sixteen x 60lb rockets beneath its wings.

Strikes were made against trains, trucks, bridges, buildings and anything else that contributed to the enemy’s infrastructure.

In the month of February, 77 Squadron flew 1007 missions and Zupp was in the thick of it, flying 50 sorties. These missions were not without resistance, as evidenced by the diarised entries that litter the now yellowing pages of his logbook. “Shrapnel hit in port nacelle.

Hole in ventral tank. Hit in port flap, port wingtip and ventral tank.” Even so, the Meteors of 77 continued to attack hard and low through the harsh Korean winter. Such tactics inevitably led to losses. 6th February 1952 was one such occasion.

When “Butch” Hannan had been brought down by ground fire near Sibyon-Ni area, Zupp was dispatched to search for the downed pilot. After his jet was hit, Zupp’s next recollection was a roar as the cockpit seemingly exploded around him.

With the canopy gone, the freezing airflow rushed by at 300 knots, he hauled back on the control column as only a matter of feet separated the earth and his ventral tank. Struggling to gain altitude and his own orientation, he reached to straighten his oxygen mask and shattered goggles.

He would later recall, that there seemed to be an inordinate amount of blood for the severity of the injury.

As he pointed the Meteor south for Kimpo, he advised the controller that he had been hit and stated he had injuries to his head. An Aussie drawl came across the frequency, “Don’t worry Zuppie, that’s your hardest part.” He had expected nothing less from his mates.

After landing, he reported to the medical staff and completed his de-brief. No further sign was found of “Butch” Hannan and he was to see out the remainder of the war in captivity. The next day Zupp was flying again and participated in two missions.

This had been Sergeant Zupp’s 48th mission. He was to complete 201 before his tour ended and he would receive the American Air Medal and be “Mentioned in Dispatches”.

The latter, in part, reads, “…and on one occasion when his aircraft was hit and he himself wounded he displayed great skill and fortitude by bringing his aircraft safely to base.”

The citation is glued discreetly in his logbook and reflects the approach Zupp had to his service in later years. Treasured, but tucked away.

In a routine report, his commanding officer had described Zupp as, “The rough diamond type who is keen to do a good job…” To those who knew Phil Zupp, the description was perfect. The subsequent comments also included, “…has been wounded in action.

Awarded American Purple Heart and Air Medal.” The enigma of Australia’s first Purple Heart had surfaced in a confidential ‘Assessment of Character and Trade Proficiency’. A document the young fighter pilot was never to see.

The events of 6th February 1952 and the award of the ‘Purple Heart’ would lie dormant for many years. In 1991, Zupp became terminally ill, succumbing to cancer after a typically short, sharp battle.

Curiously, after one procedure that had surgically removed growths from his face, the pathology report showed fragments of metal and Perspex.

On being questioned whether he could pinpoint their origin he replied simply, “I’ve got a rough idea. It’s a fair while ago now.”

Further research into the ‘Purple Heart’ uncovered an extensive paper trail that commenced just after the fateful sortie in early 1952. The first document to strike the reader is a citation from the USAF;

“By direction of the President, Sergeant Phillip Zupp, A11439, Royal Australian Air Force has been awarded the Purple Heart.

CITATION

On 6 February 1952 Sergeant PHILLIP ZUPP distinguished himself by displaying outstanding courage while flying Meteor Mark Eight type aircraft in carrying out a search for a downed pilot in an area heavily defended by enemy anti-aircraft fire.

Sergeant ZUPP sighted what he believed to be distress panels and in coming down to a dangerously low altitude to investigate he received an explosive burst of enemy fire which destroyed his canopy and wounded him in the face.

Despite shock and low altitude Sergeant ZUPP was able to regain control of his aircraft and return safely to base. Sergeant ZUPP’s outstanding courage and superior airmanship on this occasion reflects great credit upon himself, his comrades in arms of the United Nations and the Royal Australian Air Force.”

The actions of Sergeant Phillip Zupp on the morning of 6th February 1952 had resulted in the award of the first Purple Heart to an Australian serviceman.

However, despite the support of Australia’s Governor-General and Prime Minister, it had apparently been denied by a bureaucrat in London.

It was only in the final years of his life that Phillip Zupp had even become aware of being awarded the Purple Heart. If quizzed as to when he might have earned it, he probably would have lowered his pipe and said, “I have a rough idea. It’s a fair while ago now.”

The full story is told in the newly released book, ‘Without Precedent’.

By Owen Zupp