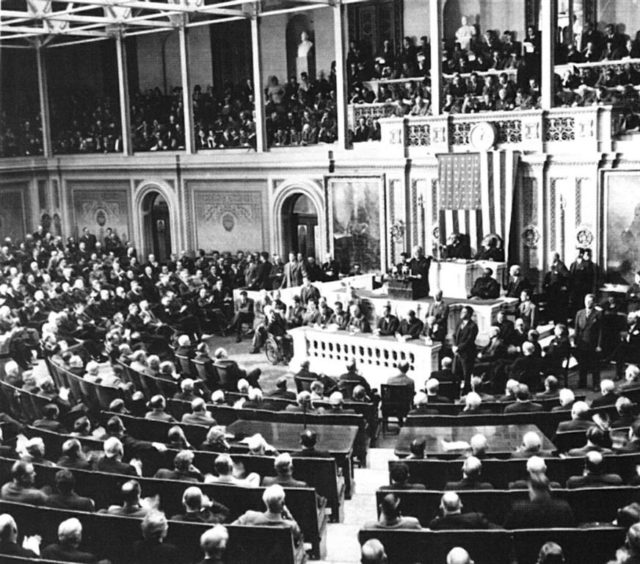

An Associated Press report described “a chorus of hisses and boos” that echoed through the chamber when the Congresswoman from Montana cast her vote. It was Monday, December 8, 1941 and the U.S. House of Representatives was assembled to ratify the declaration of war that President Roosevelt had asked for earlier in the day.

Just 24-hours earlier, an aircraft carrier task force of the Japanese Imperial Navy carried out an air raid on American military installations across the island of Oahu in the Territory of Hawaii. Although a troubling diplomatic confrontation had been unfolding for over a year between the two nations, Japan and the United States were at peace with one another at the time of the attack.

With almost two hundred U.S. aircraft destroyed, the Pacific fleet in ruin at Pearl Harbor, and 2,400 Americans killed, a national consensus had been born overnight for war with the Japanese. When the measure went to a vote in the Senate in the afternoon, it passed unanimously 82 to 0. But when it went before the House of Representatives shortly thereafter, not everyone answered “aye” when the Speaker asked for those in favor.

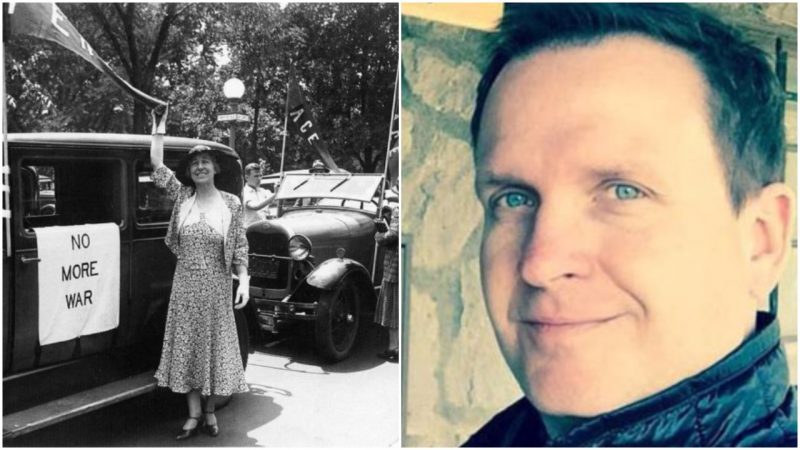

The hisses and boos came only when sixty-one-year-old Jeannette Pickering Rankin replied with a “nay” – the only opposing vote cast in the Congress that day. But it was not the first time that Representative Rankin had opposed a declaration of war.

On April 5, 1917, the Washington Times reported that she appeared to be “a woman on the verge of a nervous breakdown” as she stood to answer the roll call vote in the House of Representatives. No ordinary matter, this vote would decide the question of American intervention in the First World War.

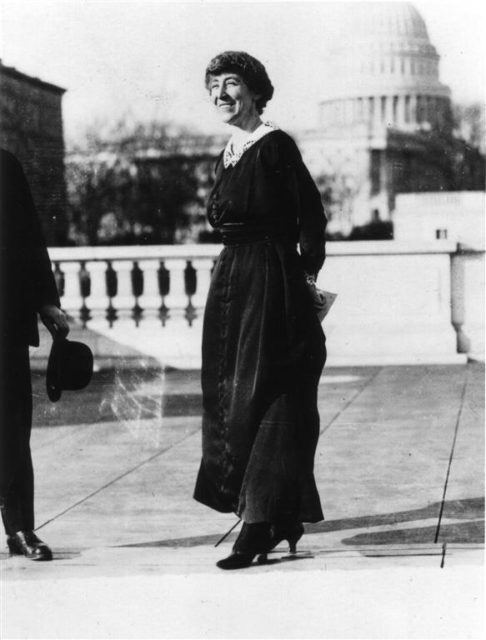

For thirty-seven-year-old Jeannette Pickering Rankin representing the State of Montana, this important moment had come swiftly after her official swearing in just three days earlier. The other members of the 65th Congress “cheered and rose” when her name had been called on that historic day because it marked the first time a woman entered the membership of the United States Congress.

In strong contrast, not a sound could be heard in the chamber on April 5th as Representative Rankin prepared to cast her vote relating to the declaration of war on Imperial Germany. With “every eye in the chamber fixed on her,” Rankin hurriedly gripped the back of the seat in front of her and spoke: “I want to stand by my country, but I cannot vote for war.”

In the final tally, the measure passed in the House 374 to 50 and the United States entered the First World War. Although Jeanette Rankin’s first vote in the Congress did not avert America’s entry into the conflict, it did make her a household name and introduce her unique blend of pacifism and feminism to a nation still suspicious of either belief.

During the twenty-five years that followed her vote against the declaration of war in 1917, Jeannette Rankin left Congress but continued her crusade of radical anti-war and social reform activism. Her boundless, unwavering energy and epic stubbornness brought her into conflict with the leadership of every organization she served, making her a political outcast even among the suffragists of feminism’s first wave.

In 1940 she reentered the Congress and eventually voted against America’s entry into the Second World War in a move that made her irretrievably unpopular. After choosing not to run for reelection in 1942, Rankin withdrew from public life only to emerge again during the 1960s to protest U.S. military involvement in Vietnam. Her crusading, therefore, also reached into feminism’s second wave at the end of over fifty years of political activity.

During that half century, gender was both a blessing and a curse for Jeannette Rankin. It provided her opportunity to serve in the House of Representatives at a time when women could not vote, but then it also provided the limits that restricted her political career.

Jeannette Pickering Rankin’s life began in June 1880 on a ranch just outside Missoula in the Montana Territory. Her father’s business success in ranching and building charted the course of her future in so far as it provided her with not just a comfortable lifestyle, but also the financial support that would ultimately allow her to pursue her interest in social reform. Whereas most young women rural Montana at the turn of the century married early and started families, the trajectory of Jeannette Rankin’s life took her instead to college and to a brief career in teaching.

Then in 1908, she moved to New York City and entered a master’s degree program in social work at the New York School of Philanthropy. After experiencing the urban realities of child welfare in a major U.S. metropolis, Rankin’s social progressivism began to explore new methods of childhood development and character building among orphans as well as cultivating higher standards of motherhood. When she returned to the Pacific Northwest the following year, Rankin continued her education by studying public speaking, sociology, and economics at the University of Washington.

Continues below

During this same time her only brother Wellington D. Rankin received an education that placed him on an altogether different career path. He attended Harvard University School of Law, became a successful trial lawyer and ultimately U.S. District Attorney, Attorney General of the state of Montana and Associate Justice of the Montana Supreme Court. In addition to that, Wellington Rankin also took over his father’s business interests when he died in 1904 and served as the executor of the estate.

Despite the fact that she was the first-born, it does not appear that Jeannette or anyone in the family expected her to take over the Rankin economic empire. Clearly the male heir (Wellington) would be the one to develop the necessary skills to manage the family assets, and so off he went to Cambridge, Massachusetts.

So brother and sister followed separate, gendered paths in education, with Wellington learning how to be a business leader and Jeannette learning to be a school teacher and exploring the social reform ideologies embraced by so many of the women active during the Progressive Era.

After spending a year as a social worker in Missoula, Spokane and Seattle, Jeannette Rankin changed paths again and turned her attentions to the movement that was sweeping the nation: woman suffrage. Beginning in 1910, she began five years of campaigning and grassroots organizing in the movement as a field secretary for the National American Woman Suffrage Association.

Although the campaign took her from coast to coast, she directed the effort in Montana and in 1914 succeeded in making it the eleventh state to pass woman suffrage. Her distinctive speaking style and fervent eloquence helped the cause and made Jeannette Rankin a rising star in the movement. At a Woman’s Day speech in Missoula shortly after winning the Montana suffrage initiative, Rankin urged her audience with these compelling words:

“All over the country, women are asking for the vote. . . . We are a force in life, a factor which must be considered in all problems. . . . While we Montana women have broader opportunities than the women of any other part of the world, we want the ballot in order to give opportunity to less fortunate women.”

Her passionate oratory and untiring efforts won many admirers across the country. One suffrage organizer in New York described how, “Her tact, her gentle feminine persuasion and her ever-ready logic made many converts to Woman Suffrage,” there.

During twenty weeks of “the most strenuous” fieldwork, Rankin demonstrated herself to be an “unselfish volunteer” and did it all for only expenses. But the accolade and admiration of suffragists throughout the United States would not last forever.

In 1916 Jeannette Rankin decided to run for one of Montana’s two at-large seats in the U.S. House of Representatives. Her implacable stamina and compelling speaking ability served her well again on the campaign trail in Montana. Former Montana legislator Tom Haines later described it:

“She was one of the ablest campaigners that I ever saw. If she heard of a vote a hundred miles up in the mountains [or] in some isolated canyon up there, she would go up and see them, drive up there and it didn’t make any difference about the roads. . . . She would go anywhere. Anywhere—a house of prostitution, it didn’t make any difference to her what it was—she would make herself at home. . . . She was a tough person; nothing phased (sic) her when she was after something.”

Thanks to these tenacious campaigning skills, along with Wellington’s political acumen and financial support, Jeannette Rankin won election to the House of Representatives on November 7, 1916. In the wake of the victory, she refused requests for interviews from reporters and did not answer telegrams offering congratulations, but issued a brief public statement saying (in part), “I am deeply conscious of the responsibility resting upon me.”

A series of circumstances unique to Jeannette Rankin and unique to Montana made this victory possible. She possessed all of the qualities of an excellent candidate and she belonged to a wealthy and influential family that could provide the financial backing and the networking necessary to win a Congressional campaign. She also ran in a state where she could actually win.

In the less populated western states women in politics became a reality sooner than back east. This was certainly true in Montana where conservatives worried that the increasing influence of an expanding immigrant population would overshadow the interests of a white minority. Enfranchising the state’s women served the pragmatic political purpose of doubling the size of the white electorate with the stroke of a pen. When Jeannette Rankin ran for the U.S. House, she ran as a Republican candidate and, unsurprisingly, attracted the state’s female voters. In a perfect example of principle meets pragmatism, Jeannette Rankin was the right person at the right place at the right time.

Her gender had opened the door of opportunity and she had walked through that door into House of Representatives on behalf of women everywhere. But the triumph of that moment was to be short lived and Jeannette Rankin was about to find herself cast out of the suffrage movement because of her personal convictions.

Continues below

Rankin believed that armed conflict was a “stupid and futile” means of settling international disputes but she was nevertheless aware that a vote against the war in April 1917 would produce a strong backlash. Major newspapers such as the New York Times and the Christian Science Monitor criticized her decision and the Helena Independent even went so far as to label her “a dupe of the Kaiser, a member of the Hun army in the United States, and a crying schoolgirl.” But for Rankin, the “hardest part of the vote” was the way it alienated her from the national suffrage movement.

Concerned that a close association with Rankin’s unpopular pacifism would damage their campaign, suffragists quickly backed away from the Montana Congresswoman. Carrie Chapman Catt, president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, told the Helena Independent that “Miss Rankin was not voting for the suffragists of the nation – she represents Montana” and “every time she answers the roll call she loses us a million votes.”

The cold shoulder that turned toward Jeannette Rankin immediately after the April 1917 vote on the declaration of war against Germany only foreshadowed the more ominous opposition that she would confront the following year. The suffragists who had supported her run for the House of Representatives in 1916 withdrew their support in 1918 when Rankin made her next political move. Earlier that year the state of Montana eliminated its at-large House seat and created in its place eastern and western congressional districts.

Rather than competing against a colleague for the western district seat or carpetbagging in the eastern district, Rankin decided to make a run for the Senate. In response to news of this decision, Carrie Catt told the Helena Independent that, “…for her sake as well as ours it is most advisable that she should quit at this stage.” To pour salt in the wound, Catt offered nothing but the kindest words for Rankin’s opponent, Democratic incumbent Thomas Walsh.

In the end, opposition to the declaration of war, as well the perception that she held sympathies for radical labor activists in Butte, turned the voters against Jeannette Rankin and she lost the election.

Undaunted by her brief foray into politics, Jeannette Rankin continued to work in the interests of pacifism and social welfare after leaving the House of Representatives, and her words continued to echo with the radical timbre that she was famous for. As a paid lobbyist, she became an advocate for child labor reform, hunger relief, consumer protection, minimum wage/maximum hour legislation and even a Constitutional amendment outlawing war.

She joined the Executive Board of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, but resigned in 1925 when she disagreed with its leadership over the organization’s direction. To Rankin, the League had “no organization, no purpose, no definite thing.” In 1929 she went to work as a lobbyist for the National Council for the Prevention of War, but her strong-willed individualism generated friction there as well. By 1939, Rankin was done with national bureaucracies. She quit the Council for the Prevention of War and decided that the time was right to re-enter the political arena.

The ominous situations in Europe, North Africa and Asia deeply concerned her because the gathering clouds of conflict suggested another world war in the making. That next year, sixty-year-old Jeannette Rankin ran for a second term in the House of Representatives. “No one will pay any attention to me this time,” she predicted, “there is nothing unusual about a woman being elected.”

When Election Day came, Rankin won her second term in the House of Representatives with fifty-four percent of the vote. Although almost a quarter century had passed since 1917, she took the oath of office in 1940 under remarkably similar circumstances. The United States was on the verge of being drawn into another world war and Jeannette Rankin could read the writing on the wall:

“I knew it was coming. . . .Roosevelt was deliberately trying to get us in the war. . . .I didn’t let anybody approach me. I got in my car and disappeared. Nobody could reach me. . . .I just drove around Washington and got madder and madder because there were soldiers everywhere I went. . . .I don’t remember whether I thumbed my nose at them or not, but I resented them.”

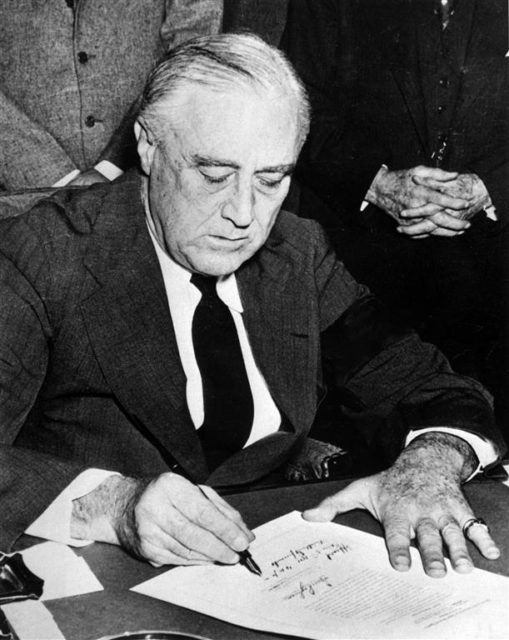

From Washington, DC, Rankin did what she could to forestall the gradual, but steady approach to war. When President Roosevelt signed the Lend-Lease Act into law in March 1941, she spoke out against it saying, “If Britain needs our material today, will she later need our men?” Two months later she introduced a resolution condemning any effort “to send the armed forces of the United States to fight in any place outside the Western Hemisphere or insular possessions of the United States.” The resolution died in the House.

Then, on December 7, 1941, forces of the Japanese Imperial Navy conducted a devastating aircraft carrier raid against U.S. bases on Oahu in the Territory of Hawaii. In a joint session of Congress the next day, Jeannette Rankin voted against a declaration of war for the second time.

Continues below

Although many other members of Congress had joined her in 1917, she was alone on December 8, 1941. Rankin justified her opposition to the measure by stating “As a woman I can’t go to war, and I refuse to send anyone else,” and “I voted my convictions and redeemed my campaign pledges.”

After the vote, Rankin very quickly faced enormous amounts of passionate and vicious criticism. Back in Missoula, Wellington wired her with a sobering update: “Montana is 100 percent against you.” Angry letters and telegrams arrived at Rankin’s office in Washington by the thousands. One letter from a Mary B. Gilson stridently placed gender at the center of criticism:

“You have turned the clock back for women! . .Thank God our country does not have to depend on such unrealistic persons as you! You doubtless flatter yourself on standing by your ‘principles,’ but inflexible principles like yours would put us under the Nazi heel. You will not hold an enviable position in the history of our times.”

In the aftermath of Pearl Harbor, Jeannette Rankin made a stand on pacifist principles at a time when the rest of the country strongly opposed them – especially when being articulated by a woman. Although 25 years had passed since her vote opposing American entry into World War I, Rankin was still being accused of damaging the cause of feminism during World War II.

Despite the fact that much had changed since 1917, and that women had been fully enfranchised for two decades by that time, one woman’s refusal to conform provoked intense emotions that hastened her exit from Congress. Rankin chose not to run for reelection in 1942 and quickly faded from the political scene. She reappeared during the 1960s in the middle of feminism’s second wave, but even that was an awkward, uncomfortable fit.

Despite the fact that the National Organization for Women named her “the world’s outstanding living feminist” in 1972, she criticized modern feminism:

“I tell these young women that they must get to the people who don’t come to the meetings. It never did any good for all the suffragettes to come together and talk to each other. There will be no revolution unless we go out into the precincts. You have to be stubborn. Stubborn and ornery.”

Jeannette Pickering Rankin died on May 18, 1973 in Carmel-by-the-Sea, California, leaving behind a unique political legacy. She was the only Member of the U.S. Congress to vote against both World Wars, and she cast the solitary vote against war the day after Pearl Harbor.

At 4:10 pm on December 8, 1941 President Roosevelt signed the declaration of war that Rankin stood alone to oppose. As the United States became a combatant power in the struggle against Imperial Japan, the pacifist views that Rankin had so passionately espoused for nearly a quarter of a century fell by the wayside as an outraged nation sought to avenge an “unprovoked and dastardly attack.”

Author: Martin K.A. Morgan

All photos are provided by the author.