War History online proudly presents this Guest Piece from Jeremy P. Ämick, who is a military historian and writes on behalf of the

Silver Star Families of America.

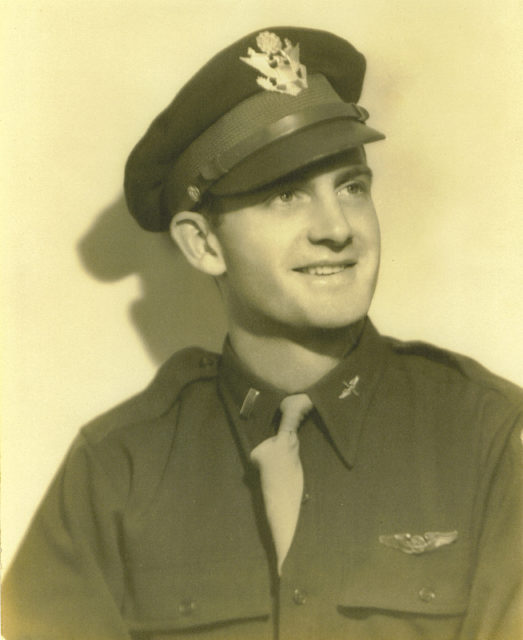

E. John Knapp has acquired the reputation as being a man who has enjoyed exploring various creative outlets such as poetry and painting. A retired architect, in the last several years he embarked upon another means of self expression by putting to paper his experiences during World War II after he was encouraged to do so by his children.

Modestly, he held up his book titled “Poet Flyer: WWII Poetry & Photographs Based on Aerial Combat,” and said, “I wanted to share the message of the three stages of my experience—before, during and after the war.”

The story of his journey toward military service began to unfold a few years following his graduation from high school in 1935 in his home state of Michigan, Knapp explained.

Working a couple of years as a youth swimming instructor and later as a chauffer for a camp director under the National Youth Adminstration—a former government program that once provided work and educational opportunities for those between 16 and 25 years of age—Knapp left the job and chose to pursue his own education.

He enrolled in Lawrence Techical University near Detroit in 1937, choosing to focus on a degree in architecture because of an interest that had blossomed many years earlier.

“I watched several homes being built while I was growing up, including my grandmother’s and uncle’s, and decided that’s what I wanted to do when I got older; I wanted to design homes.”

The young man began attending classes in the evening and gained applicable experience working as a draftsman for a local company during the day. However, he decided to leave school and enlisted in the Army Air Corps in April 1941—a choice, he said, was motivated by both his interest in flying and the realization he might soon be drafted.

Despite the approach of war, the aviation cadet decided to marry Maxine—to whom he had been introduced by a relative—in August 1941. His participation in the war was soon secured with the bombing of Pearl Harbor in December 1941. In February 1942, he left for the Air Corps induction center at Nashville, Tenn., to begin his training.

“We were there for a couple of months for basic training,” the veteran recalled,” and then I was sent to flight school at Monroe, La. While I was there,” he continued, “I decided I didn’t want to be a pilot and instead became a navigator.”

His military specialty may have changed, but Knapp remained in Louisiana to complete his navigational studies, eventually qualifying as a crewmember and receiving his commission as a lieutenant in 1943. He then traveled to Texas and was assigned to the crew of a B-17 bomber, spending the next several weeks there refining his aviation skills.

“This was back before GPS technology so we had to learn to navigate by the stars,” he grinned.

With their preparatory training completed, the crew boarded their B-17 and flew to Canada and then to Northern Ireland. After brief trips by both boat and train, they finally arrived to their duty assignment with the 100th Bomb Group stationed near the small community of Thorpe Abbotts, England.

Knapp and his fellow aviators soon began flying missions to bomb targets throughout Nazi-occupied Europe, during which they were constantly harassed by the threats of German fighters and anti-aircraft guns.

Though the veteran affirms there were many memorable missions in which he participated so long ago, including the bombing of targets “just ahead of the infantry and tanks” on D-Day, it was his crew’s sixth mission that has remained forever inscribed in the forefront of his memories.

“We usually got up at about 3:00 a.m. and got ready for the flight—showered, cleaned up, ate chow, all of that stuff,” Knapp said. “When I was getting on the plane to leave for the mission, our colonel pulled me off the flight … and I never knew why.”

During the mission, Knapp explained, his fellow B-17 crewmembers had to make a second run at a German target that was concealed by cloud cover, which gave the enemy an opportunity to sight in on the aircraft.

“The plane was hit and exploded shortly after that,” Knapp solemnly recalled.

For several years, he believed everyone aboard the aircraft had perished.

After completing 35 combat missions, Knapp chose to remain at Thorpe Abbott and was transferred to an intelligence section, spending the remainder of his time overseas preparing information on daily targets and flight routes.

When the war finally ended in 1945, Knapp returned to Michigan, reunited with his wife (whom he had not seen for nearly three years) and went back to school to finish up his architecture degree.

“One day, I got a call from the (top turret) gunner who had been on the plane that was shot down,” said Knapp. “I found out that he and the bombardier had survived and were captured and held as POWs until the war ended, but everyone else on the plane died.” He added, “What a wonderful moment that was—I still remember it like it was yesterday; to hear that he and the gunner had survived!”

As the years passed, Knapp finished the training and apprenticeship to become an architect, a career he enjoyed for several decades. He has since relocated to Jefferson City and uses his spare time to embrace his passions of poetry, painting; and, more recently, has embraced writing about his military service.

Now 100 years of age, Knapp has acquired a special perspective on World War II, one that has grown and matured from the range of experiences of which many have only read about in books.

“I have a different idea than most about World War II,” Knapp said. “We really had two major enemies—Germany and Japan—and it sure was a vicious fight. But” he continued, “both of these countries are now some of our closest friends.

“For me,” he concluded, “that’s the true meausure of how we won the war and helps give meaning to the lives that were lost.”