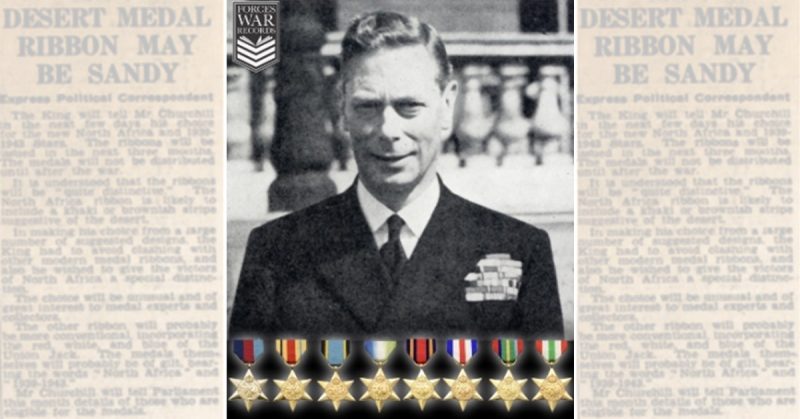

Eight different campaign stars were issued for the Second World War. The ribbons are believed to have been designed by King George VI personally and have symbolic significance, this is a belief quite widely shared and given some credence by Alanbrooke’s War Diaries.

In fact, they were designed by WWI veteran Peter O’Brien ARCA, Forces War Records has the full story from Peters son Michael O’Brien.

In his War Diaries, Lord Alanbrooke wrote of a dinner at Buckingham Palace on 15th February 1945, during which the King showed medal ribbons that were to be distributed at the war’s end. Michael couldn’t resist a smile on reading this because he saw those ribbons before either the King, or anyone else at the dinner, or any of the millions of recipients. Between the ages of seven and nine, Michael watched his late father, Peter O’Brien ARCA, design them.

Peter, born in 1900, had served in the Royal Flying Corps/Royal Air Force in the World War One. After demobilization he attended the Royal College of Art, qualifying in design in 1924, after which he worked in the Lancashire textile industry. During the depression, he moved into teaching and by the beginning of the World War Two he was Head of Design at the Manchester School of Art and living at 9, Brantwood Road, Heaton Chapel, Stockport.

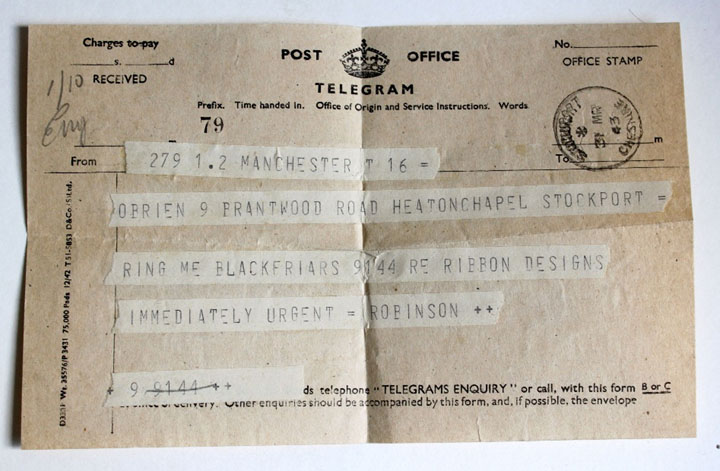

The story of the medal ribbons began about the time of the battle of El Alamein, before this little seemed to go right. Despite this, it had been decided, presumably by The King and his ministers, that all who served the country in the war should receive some recognition. discussions within in the textile industry decided to approached Michaels father Peter O’Brien. These discussions culminated in a cryptic telegram, dated 31st March 1943. (Fig. 2)

The resultant telephone conversation concluded with a request to offer some designs for consideration by the Ministry of Supply. Michael’s family were powerfully impressed with how important Peter had suddenly become because a telephone had to be installed to facilitate quick communication with Whitehall.

A domestic telephone was a comparative rarity in those days and Michael can still remember the old alphanumeric number: HEA (ton Moor) 4045. Peter had to sign the Official Secrets Act and the family was sworn to silence about the whole affair, quite a challenge for a little primary schoolboy. The work took place in the house in Heaton Chapel at nights and weekends over the next couple of years.

The first attempts were made with poster paint on cartridge paper. Peter was deeply dissatisfied as the result was matt and very unlike the appearance of the finished ribbon. He managed to persuade “Whitehall” that the designs would look so much better if they could be made with examples of dyed ribbon. So, the quaintly named Directorate of Narrow Fabrics supplied rolls of pristine white silk ribbon. Contacts in the textile trade supplied a variety of dyes and the work recommenced. For the Atlantic Star, each selvage (self-finished edge of fabric) was touched on a thin film of dye which soaked across the ribbon.

The King was insistent that the background color of the Africa Star should represent the desert sand. (Fig. 3) An Inland Telegram form was received with three orange scribbles on it. They were said to have been made by The King himself using one of the Princesses’ crayons, and he wanted that color. When a dye was found that matched, the scribbles had to be returned.

The next problem was cutting the dried dyed silk into narrow strips for assembly into the final proposals. Scissors were no good. Strips could not be cut straight enough or indeed narrow enough. They were required in multiples of 1/16th of an inch, within an overall width of 1 ¼ inches.

The solution was found by gluing the dyed silk onto paper. Paper was in short supply during the war and the brown paper bags used for the grocery rations were pressed into service. Once the glue had dried, the colored ribbon could be cut into strips, accurately, using a steel ruler and old razor blades. The strips were then reassembled into alternative versions of the same medal ribbon.

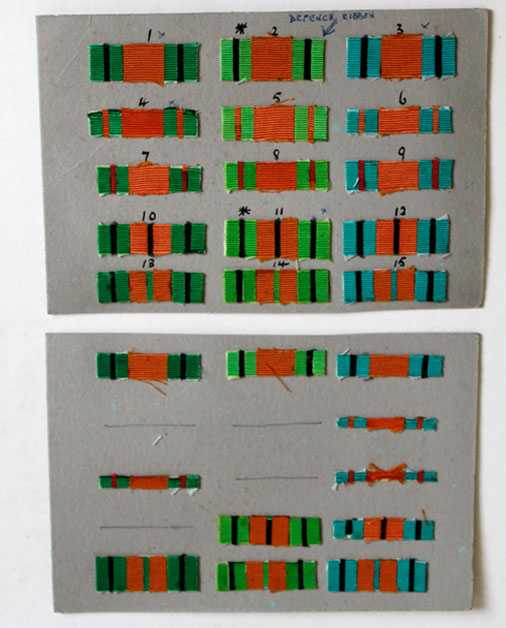

There were at least fifteen variations of each of the ribbons in the end. Each set was mounted on card and submitted to Whitehall for The King to decide which design should be woven into the ribbon.

Figure 4 shows a multiple choice card with the final choice for the Defence Medal indicated. Sometimes several were “short listed” and woven as the finished ribbon before the final choice was made. The France and Germany Star ribbon was treated in this way with three possibilities considered. (Fig.5)

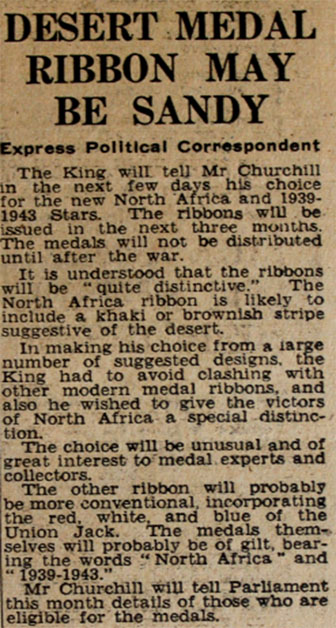

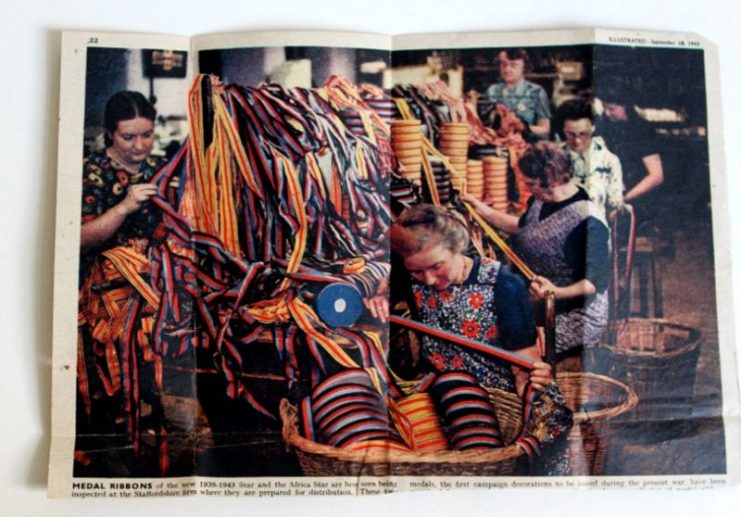

Two ribbons were announced to the public on 26th June 1943, earlier than most. They were the Africa Star and the 1939‐43 Star. They were issued in late 1943. The latter was renamed 1939-45 Star at the end of the war. The Illustrated journal of 18th September 1943 showed these two being inspected for flaws at the textile mill where they were woven. (Fig.6)

When Peter died, in 1977, much of the material used in this design exercise was found stored away in his loft. There were some of the “multiple choice” cards, copies of correspondence, some of the unused white ribbon and a swatch of some of the first ribbons off the looms. (Figs. 7 to 9)

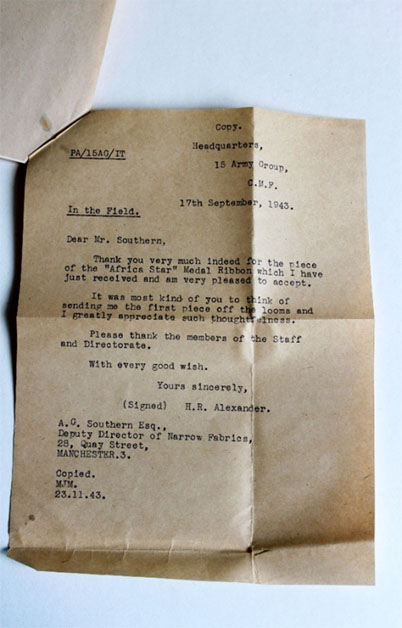

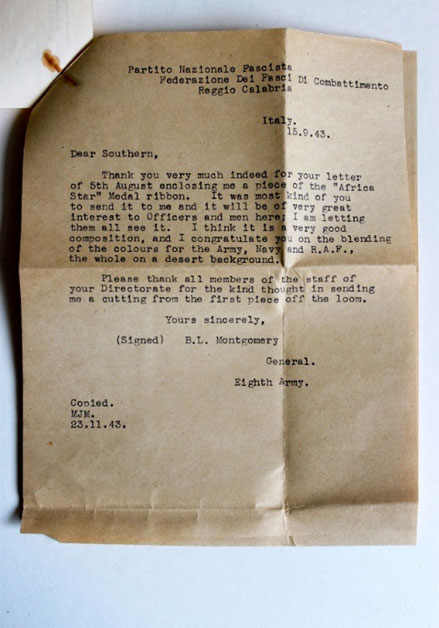

There were carbon copies of letters of thanks from Lords Alexander and Montgomery for early sight of the ribbons to be distributed to their troops. (Figs.10 & 11)

All of the material was given to the Imperial War Museum, whose then Director, Dr Noble Frankland, accepted it with enthusiasm. He said that the Museum had “a very fine collection of orders, decorations, and medals but this material relating to the way in which some of the ribbons were evolved is of very special interest to us.” Michael stated it has been a moving and evocative experience to see the artifacts once again during a recent visit to the museum.

Whenever Michael now see’s the World War II medal ribbons on the chests of old soldiers at the Cenotaph he has a certain swell of vicarious pride. Having kept the secret all those years ago it seems appropriate, over seventy years since the first person received these decorations, to put on record this background snippet of covert history.

References:

- Danchev A. and Todman D. (eds). War Diaries 1939 – 1945. F/M Lord Alanbrooke. Weidenfeld & Nicholson, London, 2001, p663.

- Desert Medal Ribbon may be sandy. Daily Express, No. 13452, 12 July 1943

- Battle of Britain Men may get Star. Sunday Express, 27 June 1943

- Frankland N. Personal Correspondence 13/01/1978

All photos provided by the author.