WWI produced many innovations in weapons design. For the first time in history, significant changes occurred during only a few years of fighting. Light machine-guns were one of those developments.

The heavy machine-gun was a vital defensive weapon that enabled troops to mow down entire formations of attacking enemy troops. It slowed down the pace of war, giving an advantage to defenders. Light machine-guns were designed to counter it and to provide rapid firepower to troops on the move.

Lewis Gun

The British stumbled into using a light machine-gun as much by accident as by design.

In the first few months of the war, the British army suffered devastating losses. Unlike some of their European neighbors, Britain had not experimented with conscription. To make up the numbers and enlarge their forces, they began raising troops known as “Kitchener armies” after the man who led the recruitment. Nor did they have the mass amount of weapons necessary to equipment the new recruits. Suddenly, vast numbers of volunteers had to be armed and quickly.

It created huge logistical problems, including how to equip units with enough machine-guns. Not only were there not enough Vickers guns for all the new units being raised, but those weapons in existing units were being gathered together for the new Machine-Gun Corps.

The solution was the adoption of the Lewis gun. It was lighter, cheaper, and easier to produce. Six Lewis guns could be made in the time it took to make a single Vickers. Designed by Samuel Maclean and marketed by the American Colonel Isaac Lewis, who had bought the design, it was the perfect answer to the gun supply problem.

The Lewis turned out to have unexpected benefits. A forced-draught air-cooling system relieved it of the weight of a water cooling system. Its rotary ammunition feed was ideal for troops on the move, and it weighed only 12kg.

However, the Lewis had some significant drawbacks. Its complex mechanisms were prone to jamming, and it needed careful maintenance. Despite the problems, the troops adopted to it enthusiastically. Its rate of fire at 450-500 rounds per minute was plenty of firepower for them. They could take their machine-guns with them on the attack.

Using the Lewis, the British developed new rush tactics in place of linear assaults. It began a change in the way fighting took place on the Western Front.

The importance of the Lewis was reinforced by the response of the Germans. They started picking off Lewis gunners in preference to other targets. Any weapons found by them, they hastily brought into service.

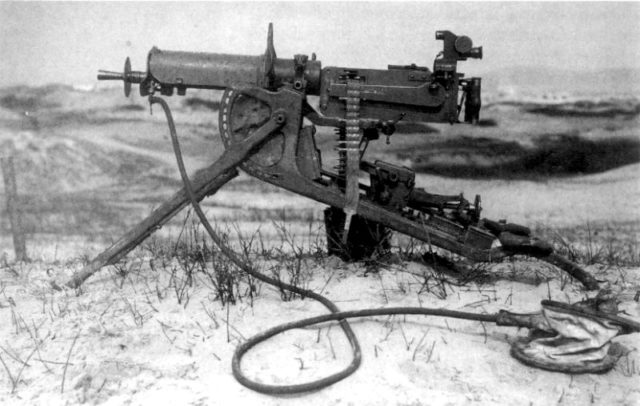

MG08/15

Not content to use their opponents’ weapons, the Germans set about manufacturing their own light machine-gun. After considering options produced by Madsen, Dreyse, and Bergmann, they settled on the Maschinengewehr 08/15 (MG08/15).

The MG08/15 was a modified version of the MG08. As well as making it lighter, the changes made it easier to maintain.

Weighing 18 kg, the MG08 was significantly heavier than the Lewis. The Germans did not refer to it as a light machine-gun. A large part of the reason for the weight was that it still used a water cooling system; though one with a smaller jacket than on previous guns.

A lighter mount and walls helped make the gun portable. A butt and pistol grip meant it could be aimed from the shoulder. Short ammunition belts and a side-mounted drum to store them added to its portability.

The MG08/15 became a central tool of the Stormtrooper tactics with which the Germans made significant advances late in the war. By concentrating firepower rather than using the guns in a supporting role, they burst through Allied lines, creating a new war of movement.

MG08/18

In 1918, the Germans produced the successor to the MG08/15 – the MG08/18. It replaced the water-cooling system with an air-cooling one, using a light fretted jacket. The soldiers who got to use it were hugely impressed with the lighter model.

Few MG08/18s were made in time to be deployed in WWI. They did, however, teach the Germans many valuable lessons which affected later designs.

Hotchkiss Model 1909

The first light machine-gun adopted by the French; the Hotchkiss 1909 was an adaptation of the Hotchkiss 1900, which they already used.

Although providing the lightness the French were looking for; the Hotchkiss 1909 was a disaster. Its weak feed mechanism made it hugely unpopular with troops.

Chauchat

Seeing the problems with the Hotchkiss 1909, the French set up a commission to find a new light machine-gun. The resulting choice was made not on military value but vested interest. It was the Chauchat.

The Chauchat used a long-recoil mechanism. It meant the gun moved a lot when fired, making it harder to maintain a steady aim. To work, the mechanism required top grade materials and very careful production; the manufacturers skimped on both.

At a weight of 9kg, the Chauchat was even lighter than the Lewis. It was its only advantage. Unreliable and hard to aim, it was a liability to the troops using it.

Browning Automatic Rifle

What others called a light machine-gun, the Americans called an automatic rifle. Their model was the Browning Automatic rifle, known as the BAR.

Weighing in at only 7.3kg, the BAR was the lightest of the widely used machine-guns. It could be carried and operated by a single person. In many ways, it was a precursor of the assault rifle.

The BAR had a fire rate of 550 rounds per minute but only had a 20-round magazine. It could switch between automatic fire and single shot, an invaluable option given its ammunition capacity. Later models were used during WWII, making it one of the most enduring light machine-guns.

Source:

Christopher Chant (1986), The New Encyclopedia of Handguns