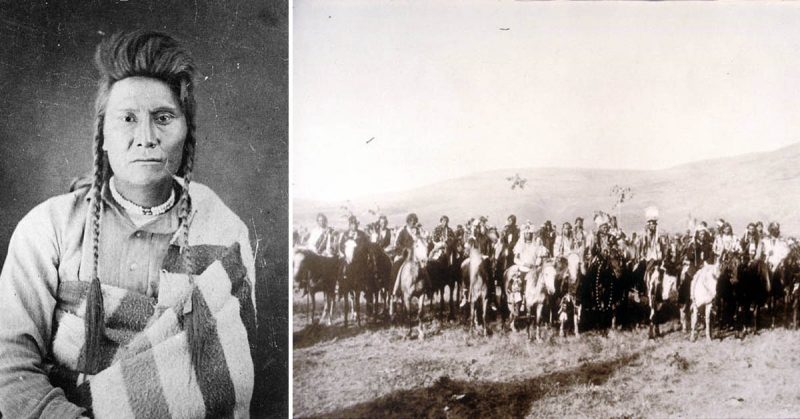

The cruel treatment of Native Americans is a long and harsh chapter in American history. Most people remember hearing about the trail of tears and the case of Indians fighting back in the Battle of Little Bighorn. Just one year after that climactic battle a string of events led to a once sprawling tribe to go on a thousand-mile journey, fighting the U.S. military along the way as they just sought freedom to live.

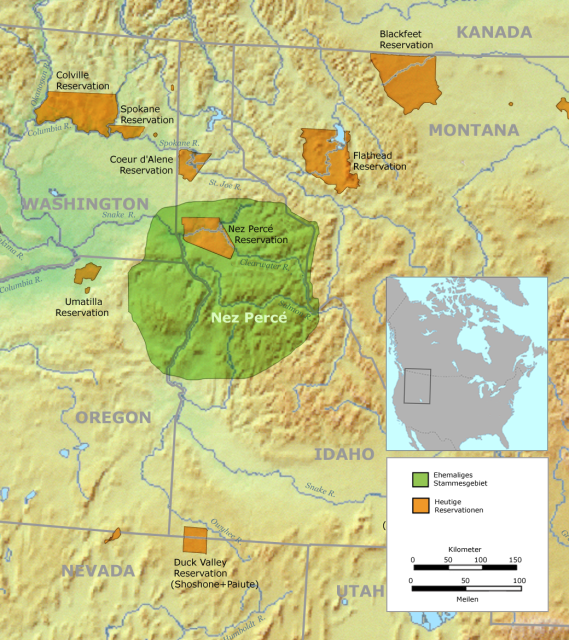

These people were the Nez Perce, a traveling tribe based in Idaho, and the corners of Oregon, Washington and Montana though they would travel as far east as the Dakotas and West to the Pacific. They held territory as large as 70,000 square km and were honorable and trustworthy according to those on the Lewis and Clark expedition.

In 1855, the Nez Perce were settled on a large reservation roughly occupying the same area as their traditional homelands. In 1863, however, the reservation shrunk to a tenth of the size, depriving the Nez Perce of much of the grazing lands home to the Camas plant, a staple of the Nez Perce diet.

In addition, American settlers often ignored the reservation’s boundaries and built within native or supposedly shared access land. This was exacerbated after gold was found in Nez Perce territories, resulting in an influx of miners absolutely disregarding any sense of land ownership. Tensions rose over the next dozen years as many of the Nez Perce simply refused to move to the new reservation and shared lands were increasingly unofficially claimed by settlers.

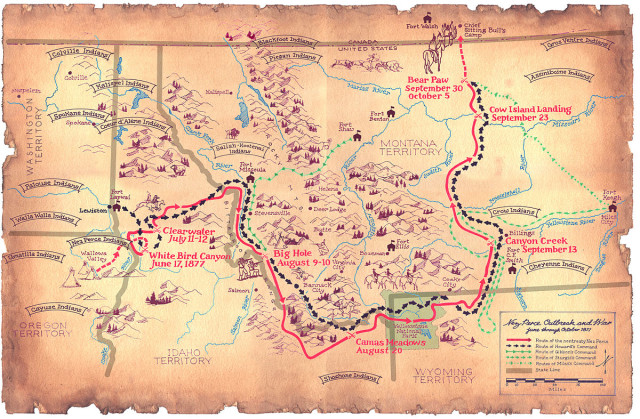

When murders of Nez Perce by white men went unprosecuted the Nez Perce retaliated and raided American settlements, killing those they knew to be especially hostile to them. This along with an earlier proclamation forcing all remaining Nez Perce to their new reservation began the involvement of the U.S. army. The bands involved in the raids knew a military response was inevitable and waited in the defensible White Bird Canyon.

On June 17th, after a two-day ride, captain David Perry led a little over 100 men into the canyon. There were about 140 Nez Perce warriors, but after securing large amounts of whiskey in raids, roughly half of them were too drunk to fight. 70 Nez Perce cavalry fought with a combination of rifles, aged muskets, and bows. As the Nez Perce were practiced with firearms by hunting, they knew the importance of making shots count and their superb accuracy quickly turned the tides of battle against the U.S. forces.

General Howard was quick to respond with a 400-man army and made a great effort to cross a river where many of the Nez Perce tribes who declined to go to the reservation resided. With their superior mobility and knowledge of the terrain the Nez Perce were able to cross the river just as Howard’s forces finished their crossing, stranding them and getting a head start eastward.

The hope was to go northeast and get aid from the crow, and failing that, get to Canada. In the first weeks of July, the traveling tribe had to form a military screen to get their people past an entrenched U.S. position at the battle of Cottonwood. Nez Perce snipers were crucial to keeping enough pressure that the U.S. soldiers could not leave their positions. Eleven U.S. soldiers were killed while the first Nez Perce death was recorded since the war’s start.

General Howard had caught up with the tribes after losing them in the river crossings and attempted to surprise the encamped Nez Perce. Despite having two to three times the soldiers, Howard started by occupying a ridge and firing howitzers and Gatling guns into the encampment, giving the Nez Perce time to disperse and form defensive positions. 25 Nez Perce rode up to the same ridge as Howard’s forces and built stone bunkers and sniped at Howard’s troops, preventing any advance.

This action allowed the rest of the Nez Perce to form defensive lines along the ridges of the Clearwater valley, forcing the U.S. forces to attack uphill for each position, while the Nez Perce simply retreated further back along the ridges and dug in again. After a night in which Howard’s men went without food or water, he decided to launch a full assault which succeeded in driving the Nez Perce from the valley, though with heavy losses for Howard’s army. The Nez Perce continued their journey, but Howard’s force needed a day to rest and recuperate before following.

The Nez Perce took the Lolo pass into Montana. Howard ordered a fort to be built and garrisoned at the bottom of the pass to stop the Indians. Captain Charles Rawn was charged with the defense but had only 35 soldiers and less than 100 volunteers.

When faced with the descending Nez Perce most of the volunteers left, leaving less than fifty to defend the hastily erected fort. An arrangement was made to peacefully pass through the remainder of the pass with the U.S. soldiers observing at a safe distance. The fort would soon be remembered as Fort Fizzle.

Once in Montana, the Nez Perce found that many residents were sympathetic to their cause, or at the very least not hostile, and they were able to trade for food and other supplies with local ranchers. Unfortunately, this kindness lulled the Nez Perce into a false sense of security and they were less than prepared when the U.S. attacked in August under commander John Gibbon.

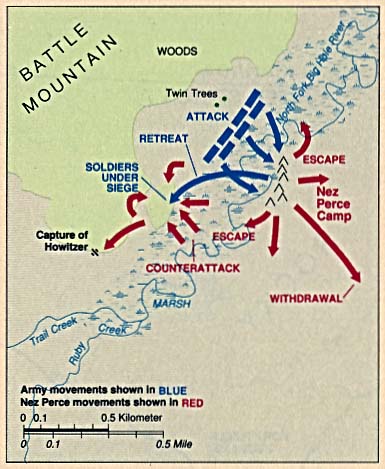

Known as the battle of Big Hole, Gibbon led 200 men into the unsecured Nez Perce position at dawn. His men shot into the tipis and set them on fire as many of the Nez Perce were still sleeping. Once they became organized the Nez Perce began sniping and targeting officers from what little fortification they could find, pushing Gibbon’s force into a nearby forest.

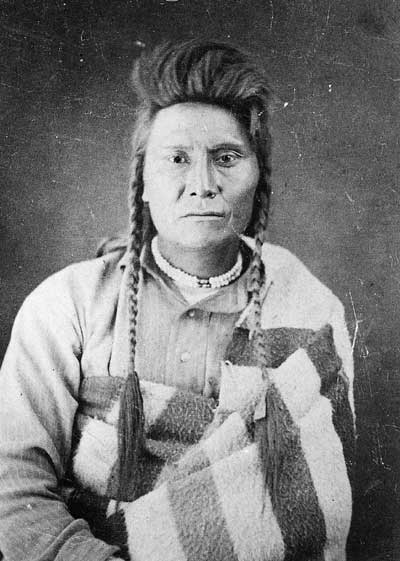

Dozens of the best warriors kept Gibbon’s army pinned down while the rest of the tribe marched away, to be joined by the warriors later. The battle resulted in many casualties for both sides and began to wear on the resolve of the Nez Perce and their Chief Joseph.

The Nez Perce realized that they still faced the U.S. military and General Howard was again on their trail. They successfully raided Howards cavalry and mules and stampeded many of them away, crippling Howard’s mobility. To prevent ambush, the Nez Perce took a longer route through Yellowstone Park before heading North through Montana again.

While in Yellowstone there were several incidents and multiple guests were killed in the park. Howard and the new arrival Col. Sturgis attempted to use their forces to trap the Nez Perce in the park, but skillful maneuvering by Chief Joseph led the Nez Perce out of the park with the two armies miles behind before they even realized what happened.

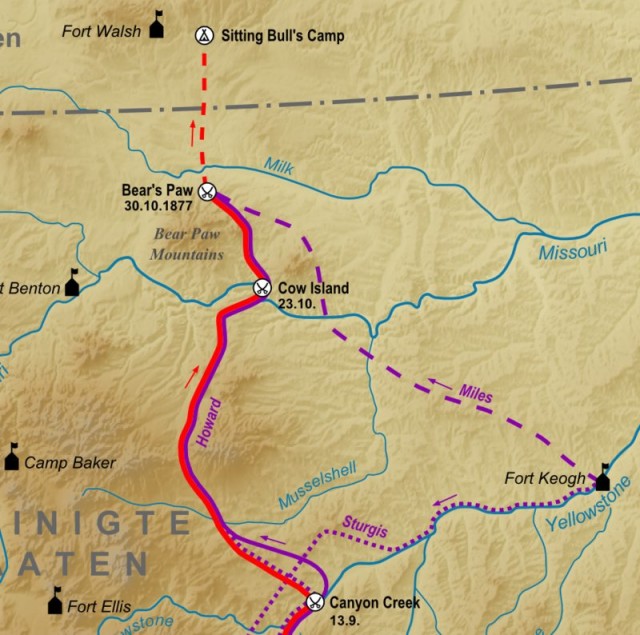

Once back in Montana, the Nez Pearce sought out their friendly Crow tribe for asylum but were met with disappointment. The Crow did not want to face the retribution of the U.S. army and so denied the Nez Perce and several Crow volunteers, even joined the U.S. forces tracking the Nez Perce. The Crow were able to steal several hundred Nez Perce horses while the Nez Perce once again fought off a U.S. attack. Disheartened and lacking spare horses, the Nez Pearce headed for Canada, hoping to join Sitting Bull’s tribe hiding out after their victory at the Little Bighorn.

The Nez Perce were hungry, tired and had many wounded when they reached the base of the Bear Paw Mountains in October. They knew that General Howard was a day behind them but had no knowledge of Col. Nelson Miles, who had gathered yet another U.S. army of around 520 men to cut the Nez Perce off.

Miles was eager to catch the Nez Perce off guard in their camp and had his cavalry charge from miles out. Once again an initial assault was successful but swift Nez Perce counterattacks pushed the cavalry back. The battle was a mess with Miles’ soldiers arriving at different times and somehow almost all of the Nez Perce’s cavalry was stolen, leaving them stranded. The battle of Bear Paw soon degraded into a siege.

The siege was a prolonged sniping affair with occasional shelling from some U.S. arterially. Only 40 miles from Canada the Nez Perce hoped Sitting Bull might send some troops down and one of the Cheifs, Looking Glass was killed by a sniper when he stood up after thinking he saw them riding on the horizon. The Nez Perce were now facing starvation and winter weather. Chief Joseph addressed his tribe and sent a message to the U.S. leaders, now joined by Howard advocating peace as follows:

“Tell General Howard I know his heart. What he told me before I have in my heart. I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed. Looking Glass is dead. Tu-hul-hul-sote is dead. The old men are all dead. It is the young men who say yes or no. He who led the young men is dead. It is cold and we have no blankets.

The little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills, and have no blankets, no food; no one knows where they are – perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children and see how many of them I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs. I am tired; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever.”

Though Howard had promised that the Nez Pearce would join the rest of their tribe in the previously established reservation, orders from higher up broke yet another promise as the Nez Perce were sent to a reservation in Kansas instead.

The Nez Perce had traveled over 1,000 miles and fought several battles and skirmishes almost always outnumbered in terms of total soldiers. They gained nation-wide popular support and even members of the military lamented the outcome but knew that they had to prevent the Nez Perce from “winning” especially so soon after the disastrous Battle of Little Bighorn.

A tragic tale, but the Nez Pearce culture does continue to this day and they will always be remembered for their bravery against overwhelming odds.