The defeat of a Spanish invasion force in 1588 was a moment of great patriotic pride for Elizabethan England. The nation’s sailors had driven off the vast menace of their Catholic enemy. In reality, the Armada was doomed for a whole host of reasons, only some of them the work of the English.

Unrealistic Expectations

King Philip II of Spain had a poor understanding of the limitations his scheme faced. Believing that God was on his side, he originally planned to send his fleet out in winter without worrying about the weather. A previous incident when English ships fled a fight led him to consider the English sailors spineless when in fact these had been English supply vessels whose contract with the French was to transport goods, not make war.

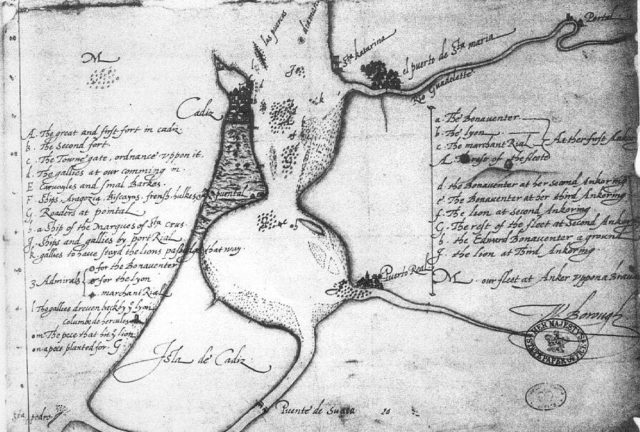

Drake’s Raid on Cadiz

As the Armada was being prepared, the English admiral Sir Francis Drake launched a daring raid on the Spanish port of Cadiz. Blockading traffic up and down the coast, he disrupted the preparations so severely that the invasion had to be postponed. Originally due to set sail in the winter of 1587, it was put off until 1588. When it did, a shortage of seasoned wood for barrel staves – again caused by Drakes’ raiding – meant that supplies of food and water went off.

The Death of Santa Cruz

The Marquis of Santa Cruz was Spain’s greatest admiral and one of the key figures in planning the Armada. His death in the winter of 1587-8 left the Armada without one of its most skilled leaders. Some even said that he died because of the Armada, his heart breaking from the certainty that it would fail.

Medina Sidonia

Santa Cruz was replaced by the Duke of Medina Sidonia. While not the worst of commanders, Medina Sidonia had not been selected for his skills as an admiral, but because his noble birth gave him the authority to command the Spaniards serving under him.

Recruitment Problems

The Prince of Parma, assembling the army of invasion in the Low Countries, struggled to gather the soldiers he needed. Lack of funds limited the troops he could recruit locally. Many among the forces coming from Spain died on the long march to Holland. Bad weather and poor nutrition took more men out of the equation. On top of this, the rush to recruit in time for the Armada meant that many men had not served in the colonies, the method Spain used to harden its fighting men. Even if they had landed in England, they would have been a weakened and weary fighting force.

Technological Obsolescence

The power of the Spanish navy lay with her galleys, which famously defeated the Turks at Lepanto in 1571. These oar-powered vessels each had a ram at the prow. They would smash into enemy ships, and if that did not sink them, then they would launch a boarding action, turning a naval battle into a land fight at sea. The ranks of rowers prevented canons from being mounted along the sides, so instead a limited number were fitted at the front.

By the 1580s, these vessels were becoming obsolete. Powerful sailing galleons could have rows of cannons mounted along their sides, giving them more firepower. It was ships such as these that smashed the Spanish at Cadiz, in conditions theoretically favorable to the oared galleys.

And so, with less than a year until their invasion, the Spanish found that four out of every five of their ships was obsolete. Though they found alternatives, much of their naval might had been lost.

John Hawkins’ Ships

Under the guidance of John Hawkins, the English spent the decade from 1578 rebuilding their fleet. Hawkins saw ways to build a far superior galleon. Fore and aft castles were lowered for stability. Hulls became longer and narrower, increasing speed, maneuverability, and firepower. By 1588, half the Royal Navy consisted of ships to this new design, and most of the rest had been rebuilt to Hawkins’s specifications.

Fewer Gunners

The Spanish lacked experienced gunners on their ships. In the English fleet, on the other hand, roughly one man in ten was a gunnery specialist, meaning that every gun crew was supervised by someone with the relevant skills and experience. As a result, when the battle came, the English fired two or three times faster.

Inferior Ammunition

The Spanish carried more ammunition for their cannons than the English, but it was not as good. Spanish iron ore was inferior in quality to that found in England. The situation was made worse by the rush to produce ammunition for the expedition. To speed up production, canon balls had been cooled in water, weakening their structure.

For some of the large bore guns, money had been saved by using stone ammunition. This often disintegrated when fired, making it deadly at short range but nearly useless for long-range inter-ship shooting.

Inferior Guns

Better metallurgy also allowed the English to produce shorter cannons while retaining their range and power. Combined with specially designed naval gun carriages, this allowed the guns to be pulled in and reloaded more quickly.

The Weather

Even before they reached their destination, the ships of the Armada were twice scattered by storms. Some were damaged, others lost, and there were long delays while they regrouped. It was an omen of what was to come, with storms smashing the fleet as it fled the English and limped home around the British Isles.

Howard Used the Wind

The obvious move for the English fleet would have been to block the Spanish by standing in their way across the Channel. But with the wind coming out of the west, this would have allowed the Spanish to close with the English, taking advantage of Spain’s tightly packed formations and experience in boarding actions.

Instead, Admiral Lord Howard led the English around the Spanish so that they were sailing behind them. From this position, they could fire at the Spanish ships, making use of their superior gunnery, with little risk of close quarters action.

Fire Ships

The English use of fire ships against the Spanish fleet moored at Calais did not sink any enemy ships. However, it forced the Spanish to scatter, ships becoming damaged as they collided with each other, giving the English an advantage in the days that followed.

Source:

John Tincey (1988), The Armada Campaign 1588.