Manning a remote island fort, seemingly without any imminent danger on the horizon, must have made for a fairly comfortable post. That was the situation on Guam until June of 1898, during the outbreak of the Spanish and American War.

Guam had been held by Spain since the 1660s. Spain had communicated with officials on the island on April 14, 1898, but the war was yet to be declared. When it was, authorities forgot to communicate the news to their forces on Guam.

The United States was quick to take action and decided that seizing several Pacific islands would give it leverage in years to come. Guam, in particular, would be a great coal replenishing pit-stop for U.S. naval ships.

Henry Glass, the captain of the USS Charleston, was anchored at Honolulu when he received orders to take his ship and a few transporters into the Pacific. When they were underway, he received new orders, which told him to head to Guam, seize the port, destroy all fortifications, and take soldiers and government officials into custody as prisoners of war. His superiors told him that the mission wouldn’t take him “more than one or two days.” That estimation proved to be correct.

While en route, Captain Glass performed drills with one of the transporters, the SS City of Peking, because he had heard a rumor in Honolulu that there was a Spanish gunboat in the Guam harbor. However, when they reached the island on June 20, they were surprised to find that there wasn’t a whole lot going on. The only boat anchored there was a Japanese merchant ship.

They toured around the island until they found Fort Santa Cruz, which didn’t seem to be lively either. Partly because he couldn’t tell exactly what was going on at the fort and whether or not it was occupied, Glass fired 13 rounds with 3 pounder guns.

When after a time he received no retaliation or response, the captain dropped anchor ‘taking control’ of the desolate and seemingly unused harbor. The apparent lack of any activity at all from the island spurred Captain Glass to send an officer to the Japanese vessel to find out what it knew about Guam and its inhabitants and governmental status.

As he was sending this officer out, he must have been surprised to see a boat flying the Spanish flag on its way toward his own ship. Four men, including Lt. Garcia Gutierrez, Spanish Navy port commander, and Dr. Romero, Spanish Army Port Health Officer, boarded the Charleston with the intent of showing friendship and welcome to their visitors.

According to the July 5, 1898 edition of the San Francisco chronicle, the men apologized to Captain Glass for not returning his “salute” – the thirteen shots fired – and told him if they could just borrow a little gunpowder, they would return to shore and respectfully reciprocate. They were even nice enough to ask after the crew’s health and to try and engage in friendly conversation.

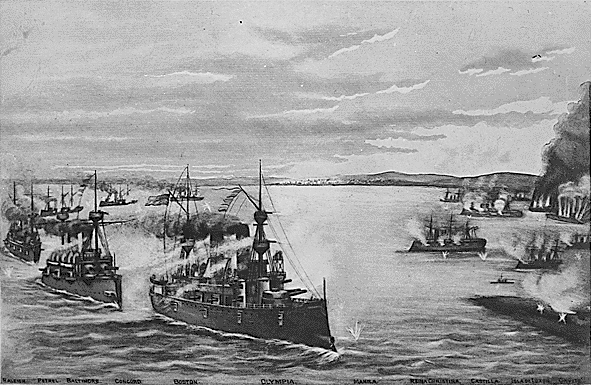

How sad it must have been when Captain Glass informed them of Spain’s defeat at Manila, his intention of taking Guam, and that when they had boarded the ship they had become prisoners of war.

Glass, in turn, learned that the island was not greatly fortified and the Spanish military presence was merely 54 Spanish soldiers and 54 Chamorros (indigenous peoples of Guam) armed with Mausers and Remingtons 45-90s. The four cannons peering out from the port were nearly unusable, and besides, didn’t have that gunpowder.

At the end of the exchange, the now beleaguered Spanish officers were allowed to return to the island with the mission of informing the governor that the U.S. was at war with Spain and that he must come aboard the Charleston immediately to discuss terms with Captain Glass.

The governor, Juan Marina, responded that under Spanish military law he would be unable to come aboard the Charleston, but that he would welcome Captain Glass on the island with the assurance of the captain’s safety.

The governor was a bit insulted when it was not the captain who came ashore, but an officer who then informed him that he had 30 minutes to submit surrender. The governor took exactly 29 minutes and addressed his reply to Captain Glass. He was further miffed when the lieutenant, LT. William Braunersreuther, opened the letter himself despite the governor’s warning not to.

The letter read that Governor Marina was reluctant, but had no choice.

“Being without defenses of any kind and without means to meet the present situation, I am under the sad necessity of being unable to resist such superior forces and regretfully to accede to your demands, at the same time protesting against this act of violence, when I have received no information from my government to the effect that Spain is in war with your nations.”

The forlorn but brave Governor Marina wrote a letter to his wife before he and other officials and soldiers became prisoners of war aboard one of the transport ships.

Captain Glass contemplated his options, but ultimately decided that it wasn’t worth trying to destroy anything that was a ruin in the first place. The fort was so neglected that it would be of no use to anyone. Instead, they spent their remaining day there getting coal to the ships.

One wonders what Marina and the Spanish soldiers felt when they finally did hear Captain Glass fire a salute to the U.S. flag he had just raised at Fort Santa Cruz to the music of the Star Spangled Banner just before leaving Guam.