While Japan is today known as a leading nation in terms of technology, this was not the case in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. After a long period of international isolation, Japan finally opened itself up to the world and realized that they were behind the times, still using as they were a large amount of outdated technology.

The Japanese now had the opportunity to start fresh, by opening up to the world.

They took full advantage of the various western nations to shop around for the best technologies and especially the best military hardware. The Japanese also sent advisors to learn army tactics and training methods from the Prussians and other European powers. Perhaps the most important result of this policy was the wholesale imitation of the British navy. The new emphasis on training was taken to heart by the new and growing Japanese navy and crews drilled constantly on their newly constructed modern naval fleet.

Battleships were built with the latest technologies including better reinforcements for the hulls and more accurate targeting systems. Though it may sound trivial, many of the larger Japanese guns had omnidirectional reloading meaning they could continue to point in any direction and continue firing. Many other ships built just prior to this point had to face their guns a particular direction meaning an attack had to halt while the turret turned and after reloading would have to reacquire a target.

Russia was an established world power by the early 1900s and was confident when tensions with Japan broke into an all-out war over ownership of the Korean Peninsula. Japan had been seen as an odd and backward country, and though they might have some new technology they were assumed to have little ability fighting modern wars.

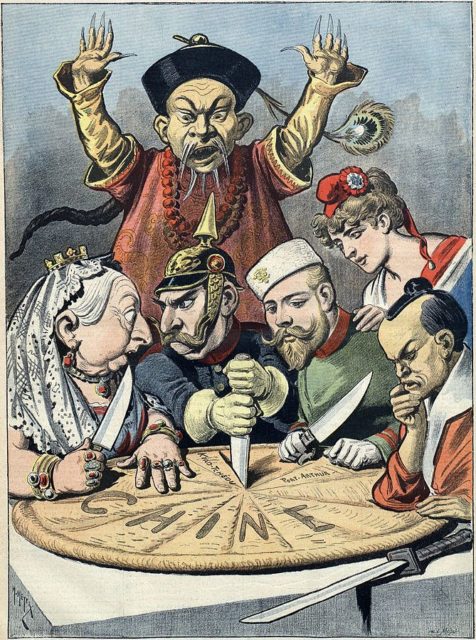

The Russians had control of Port Arthur to the West of the Korean Peninsula as well as the port at Vladivostok to the northeast. The Japanese targeted the more isolated Port Arthur by land and sea. One of the first engagements of the war was a surprise Japanese torpedo attack against the Russian ships in the harbor, causing minor damage, but greatly lowering Russian morale. Russian pride was further damaged on land as the Japanese army quickly swarmed through Korea, overwhelming Russian forces.

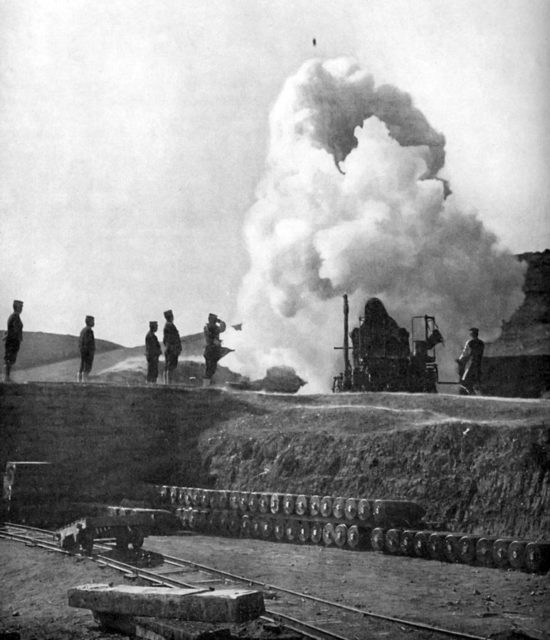

The Russian navy tried and failed to break the naval blockade, actually losing a battleship and their commander Stepan Makarov, to a mine. Too demoralized to go on the offensive, the ships sat as the Japanese army pushed to an elevated position just outside of Port Arthur. From here the Japanese were able to land artillery that had a longer range than the Russian battleships and shells soon poured into the port.

Three Russian battleships were destroyed within a week as they could not retaliate, nor did they have the confidence to try to break out. In an act of defiance and resolve, the Russian battleship Sevastopol sustained five hits from the heavy land artillery and survived some 100 torpedo attacks over three weeks. It was only just before Port Arthur surrendered when the crew finally scuttled the ship to keep it out of Japanese hands, sinking it at an angle to keep the Japanese from being able to recover it.

During the siege, the Russian Baltic fleet was ordered to sail on a round-the-world journey, all the way down the Atlantic, through the South China Sea and then to relieve the siege of Port Arthur. The 18,000 nautical mile and the eight-month journey were insanely expensive and fraught with logistical difficulties due to the amount of coal required to power the fleet. Coal was often simply piled on the decks of the ships as it was frequently bought at sea from merchant ships while on the way to Korea.

The Russian Navy suffered a huge amount of damage in an unprecedented fashion, under fire from land-based guns. Meanwhile, the Japanese had developed a system of tunneling under the land fortifications and setting off massive bombs to collapse the Russian positions. These explosions were massive and demoralizing as they almost always led to a successful Japanese offensive. The Russian garrison would soon surrender. The Japanese had paid a high price for the victory as the constant pushing for elevated positions proved costly in terms of casualties, but their strategic gain was worth it as now only Vladivostok remained for Russia.

The land armies had now grown in size as Russian reinforcements brought their core force up to 340,000 troops and 800 pieces of artillery while the now consolidated Japanese forces numbered 280,000 troops and 500 pieces of artillery. The two met outside the Chinese town of Mukden.

The Russians had a larger army, but the Japanese had the now veteran 3rd army, who were now finished with the attack and siege of Port Arthur. Japanese general Oyama’s plan was to attack in a crescent formation with emphasis on the flanks while sending the 3rd army in a wide flanking attack. His plan worked as the battle unfolded in late February the two sides clashed in the largest land battle since the Battle of Leipzig.

The wide flanking of the 3rd army made the Russian commander, Alexei Kuropatkin, respond by taking several divisions of troops to head off the attack. This only scattered and confused the Russian army and it slowly collapsed over weeks of fighting while the Japanese forces surrounded them more completely each day. By the 9th of March 1905, the Russian commander realized all hope was lost and attempted a retreat. Seeing this the Japanese were given orders to pursue and destroy. The Russians fled so quickly that nearly all of their 800 artillery pieces, were left behind along with many of their wounded and supplies.

The battle of Mukden was a complete Japanese victory, but it was won at a high cost. 75,000 casualties were sustained by the Japanese with 85,000 casualties for the Russians. The Russians were defeated, even though they had a slightly larger army, but they had fewer artillery pieces and was low on supplies. The outcome of the battle was an overwhelming strategic victory for the Japanese.

The Russian Baltic Fleet – now referred to as the Second Pacific Squadron – were quickly approaching the Tsushima Straits just south of Korea. They had learned of the fall of Port Arthur while around Madagascar and the men were increasingly demoralized. It was decided that the only real move was to head to Vladivostok. The Japanese admiral Togo knew this and had his navy prepared to intercept them in the straits.

On May 27th, the two forces met. The Russians had eight full battleships, some relatively new and some slightly dated. They had a moderate number of coastal battleships, cruisers, and other support ships. The Japanese had only four battleships, but many more cruisers and a several dozen light torpedo boats. Togo achieved an early, though imperfect, “crossing the T” action, cutting across the path of the Russian ship column.

As Togo’s ships crossed in front of Zinovy Rozhestvensky’s ships, Togo made the bold decision to abruptly turn his column around to directly engage his ships. This turning maneuver placed almost every one of Togo’s ships in a vulnerable position during the turn, but the Russian crews were not efficient enough to make the most of the opportunity. Once the turns were complete the Japanese engaged with a ferocity that overwhelmed the Russians.

A combination of Japanese training and their earlier experiences against the other Russian navy proved invaluable during the battle. The Russian ships were torn apart and some caught fire quite easily as the Japanese used explosive shells and several Russian ships had coal or remnants of the coal piles on their decks. One sailor remarked that he saw metal plates catch fire all of their own.

The Russian admiral was severely wounded and the navy quickly fragmented into several groups, relentlessly pursued by the Japanese. After nightfall, the Japanese organized a three-hour long attack by their torpedo boats. The ferocity and zeal of the attack were so great that some of the torpedo boats collided with larger Russian vessels during the night as they tried to get into the fight. This and some Russian retaliation resulted in the only Japanese losses of the battle.

Most of the war up to this point was a series of Japanese strategic victories gained at a high cost. The battle of Tsushima cost relatively little for the Japanese as they sustained roughly 500 dead and wounded, compared to 10,000 Russian killed or captured. Nearly all of the Russian ships were sunk or captured. It was a victory on the scale of Trafalgar and was a humiliating defeat for the Russians, who were soon forced to a peace treaty.

Japan gained recognition on the world stage and would eventually gain enough naval strength to challenge the U.S. for control of the Pacific during WWII. In fact, a young officer wounded at Tsushima would later become Admiral Yamamoto, who led the attack at Pearl Harbor.

By William McLaughlin for War History Online