Many consider bitter house to house fighting to be a 20th-century invention, and a 21st-century norm. But in 1809 one Spanish city, Zaragoza, resisted French occupation for two months.

By the end, Spanish and French forces were firing at one another from between houses, across streets, and even from either end of a church, leading to terrible destruction across the city.

The leadup to the battle began over a year earlier, when Zaragoza was first attacked. French forces under Charles Lefebvre-Desnouettes were repulsed by a garrison of irregulars with a few trained troops.

This embarrassing defeat brought Napoleon to the Spanish peninsula, where his troops quickly achieved a series of victories. But the north eastern corner, including Zaragoza, still eluded the French.

On the 23rd of November, 1808, the Spanish were defeated at Tudela, only 85 kilometers from Zaragoza. While the Spanish were defeated in the field, their armies were able to flee east. 17,000 Spanish troops arrived in Zaragoza to supplement General Palafox’s force already stationed there. While they had escaped death once, their current situation was still tenuous.

But shortly after the battle of Tudela the French made a costly mistake. Rather than attack Zaragoza as soon as possible, Marshall Ney’s troops were pulled back to protect the road to Madrid, which was threatened by the Spanish general Castaños. Thanks to Ney’s removal, the siege had to be postponed until the French could muster enough troops to attack.

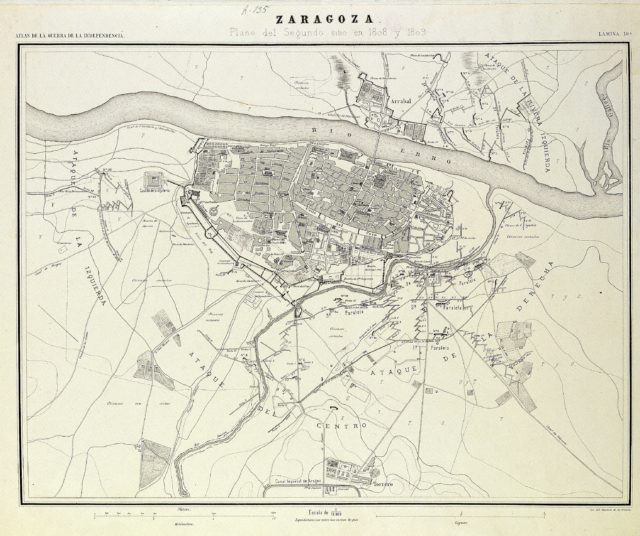

This gave the Spanish the precious time they needed to prepare, and they immediately set about establishing stronger defenses. Palafox, understanding the city’s landscape, knew that even if the walls fell, they could stall French invaders in the streets. Additionally, the city was surrounded by convents, which were turned into small fortresses.

The Rio Huerva, which runs on the eastern side of Zaragoza, was turned into a moat, with two more convents protecting it.

Within the city itself, each block of houses was made into a fortress. Made of fireproof adobe, the houses had tunnels and passages dug through their walls, allowing troops to move from one end of the block to the other without being seen. The churches within the city’s walls were fortified with 160 cannons, many of which were saved from the battle of Tudela. These were used to fire grapeshot down the major streets and passageways around the city.

To man this sprawling fortress town, Palafox had the 17,000 survivors of Tudela, to which he added around 12,000 new recruits from the city itself. In addition to this infantry force he had 2,000 cavalry, and around 10,000 armed civilian volunteers. These men were fighting on their own soil, many knew the city well, and they were all willing to fight to the death to defend Spain.

Palafox’s future adversary, Marshal Moncey, only had 15,000 troops. But on the 15th of December, a new force had arrived from Germany, adding 23,000 infantry, 3,500 cavalry, 3,000 engineers and 60 heavy siege cannons. This new French force, marched towards Zaragoza, arriving there on the 20th.

The first wave of combat commenced the next day, with a thunderous French bombardment and infantry assault. By the end of the day, they had captured Monte Terrero, a high point south of the city. This gave them an even better vantage point, and they began bombarding the southern Spanish wall as preparations were made for their push into the city itself.

Despite a failed assault on the western side of the city, they were able to take the Pillar Redoubt, to the south, on January 15th. This put them only meters away from the city walls, separated only by the river Huerva. But the Spanish had blown the bridges as they retreated.

Zaragoza awoke the next morning to find nearly all of their outer defenses either destroyed or in French hands. During the first siege, the walls had failed almost immediately, and Palafox knew not to trust in them. Instead, he used them to buy his men enough time to finalize their defenses within the city itself.

He pulled his infantry out of the redoubts and defenses and stationed them in the small fortress blocks erected throughout Zaragoza.

The French crossed the river Huerva on January 24th, establishing three beachheads just outside the Spanish walls. After three days of preparations they made three breaches into the century-old fortifications and poured infantry into the city. While this would have been the end for most sieges, in Zaragoza it merely marked the beginning of the worst fighting.

While Palafox was certainly ingenious for his street fighting strategy, he hadn’t expected the French to predict it. Marshal Lannes, who had replaced Moncey, chose to treat each individual city block as a standalone siege. While this certainly saved French troops from higher casualties, it prolonged the conflict.

This meant that the disease and sickness which had already taken root in both armies had free range to reap as many lives as it could. Each army found itself fighting two battles, one on the battle and one in the hospital bed. The Spanish were certainly losing both, being slowly pushed back throughout the city, and with nearly their entire fighting force suffering from disease. Of their original garrison of 32,000 men, only 8,495 were able to fight by February; the rest were either dead or ill. But they still put up an incredibly tough defense, leading to some of the most horrific street fighting of the 19th century.

This hard fought defense had a strong effect on the morale of the French troops, who only saw a steady stream of Spaniards shooting at them. It would take days to take each fortified block, and the soldiers were growing weary. To ease their discontent, Lannes launched an attack on the north of the city on the 18th of February. They captured San Lazaro, which gave them a suitable position for artillery.

They began bombarding the city from the north while pushing forward from the south. This finally broke the Spanish will to fight, and Palafox sued for surrender on the 19th. The initial request was refused, and Palafox resigned his control of both the city and his troops. A civil council sued for peace on the 20th of February, 1809, this time, it was accepted.

The city was surrendered, with the 8,000 remaining troops being offered a choice: imprisonment, or service for Napoleon. Nearly all chose imprisonment. After the massive destruction and sickness which swept the city, it was agreed that personal property would be respected, and the city was not sacked.

This allowed what was left of the civilian population to begin to recuperate from the horrors of the last two months. In all, 54,000 Spanish troops and civilians were killed, either by French attacks, or disease. The French lost only 4,000 to battle, and 6,000 to disease.

Zaragoza was almost a foreshadowing of future wars. While the intensity of fighting in the city would later be overshadowed by battles like Leningrad and Stalingrad, it shouldn’t be overlooked. The tactics employed by both sides were surprisingly advanced, and the high civilian death toll has become all too familiar to anyone studying 20th and 21st-century wars. It should, perhaps, go down in history as one of the first modern sieges.