Acting Sergeant Dipprasad Pun of the Royal Gurkha Rifles was the lone guard on duty, patrolling a small two-story outpost on the edge of Helmand province in Afghanistan; it was in September of 2010 on a cold, lonely night. The 31-year-old NCO was one in a long line of dedicated Gurkha militia who had served with the British forces since 1815.

In the beginning, he thought it might be a donkey or a cow, but when he went to reconnoiter, he saw two Taliban insurgents digging a trench for an improvised explosive device (IED) at the front gate of the outpost.

All of sudden a cow or a donkey or something honks out some noise outside the checkpoint where the Sergeant is sitting down quietly with his buddies; seriously, that’s how this story starts. Sgt. Pun automatically moved his head to look toward the noise and no sooner did he look out the window when his eyes instantly fell onto to two men kneeling in the middle of the road handling some kind of device. Pun’s head immediately started spinning, and alarm bells started ringing, and this combat-savvy Gurkha quickly sprang to his feet and hurried up the ladder to the top of the stockade to get a better look. Pun hollered at them to identify themselves. They sure did. The next thing you know, bullets are flying everywhere.

And now, suddenly, the peaceful silence of the Afghan landscape was filled with 7.62 mm bullets, epic vulgarity, and the familiar white streaked contrails of rocket-fired grenades. Before Pun could hardly blink an eye between 15 and 30 Taliban warriors initiated an attack on the outpost. Gunfire was zipping in from every direction; rocks and smoke were getting stirred up everywhere.

‘I tried to kill as many as I could because I thought I was going to die.’

But then, after a brief, frozen moment in time, the infuriated Sgt. Pun quickly and instinctively kicked into ‘Gurkha Mode’. In a moment of uncontrollable Berserker precision, Pun grabbed the powerful machine gun that was located on the roof, and said to himself that if he was going to die he was going to make goddamned sure that he wasn’t going to die alone – ‘I’m taking as many as possible of those Taliban -explicit- with me.’ With a mighty yell, the 5′ 7″ Sergeant yelled “I WILL KILL YOU ALL” in his native tongue. He grabbed the machine gun from its support and started firing chaotically at everything in sight.

Suddenly, he realized that he was totally surrounded and that the insurgents were about to launch a carefully planned attempt to overrun the complex. The Taliban opened fire from all sides, demolishing the patrol position where Sergeant Pun had been on duty only a few minutes previously. Using the roof as his defensive position to protect the base, the Gurkha remained under continuous fire from AK 47s and grenade launchers for more than a quarter of an hour. During this firefight, most of the insurgents were around 50 feet away. But at one point, he turned to see a ‘gigantic’ Taliban fighter looming over him. The Gurkha soldier grabbed his machine gun and fired …. and kept firing at the militant until he fell off the roof.

When another insurgent tried to climb to his position, the Gurkha tried to shoot him with his SA 80 rifle, but it didn’t fire, either because it had jammed or because the rifle was out of ammunition. He was going to throw a sandbag, but it had not been tied, and the sand fell to the floor. Then he grabbed the tripod that supported his machine gun and threw it at the advancing insurgent while shouting in Nepali ‘Marchu talai’ (‘I will kill you’) and knocked him from his position. When the heroic Gurkha had used up all his ammunition, there were still two insurgents attacking his position, but he exploded a Claymore mine to fend off the attack.

At this point, his company commander, Major Shaun Chandler, with reinforcements, arrived at the checkpoint, praised him with a slap on the back and asked how he was. In total, he fired 250 machine gun rounds, 180 SA 80 rifle rounds, six normal grenades, six phosphorous grenades, five grenades from the rocket launcher and one Claymore explosive device.

The only weapon he did not use was the traditional Kukri knife; carried by Gurkhas because he didn’t have his with him. Sgt. Pun, who is married, is originally from Western Nepal; the village of Bima, and now lives in Ashford, Kent. His father and grandfather were also Gurkhas. His medal citation mentioned that his gallantry saved the lives of his fellow soldiers at the outpost at the time and prevented the checkpoint from being overrun.

The citation reads, in part: “Sgt. Pun couldn’t know how many enemy militants were attempting to overcome his position, but he searched for them from all positions in the compound, despite the danger, steadfastly moving forward to reach the best position to repel their assault.” Major General Nicholas Carter was commander-in-chief of the combined forces in southern Afghanistan, including the British forces, during Cpl. Pun’s deployment. He praised the soldier and the Gurkhas fighting in the Mercian Regiment, for their heroism in receiving these awards today.

The senior officer, who has received a commendation from the Queen for his leadership role in the Middle East said, ‘Their efforts have been outstanding. It has been my privilege to have members of the Royal Gurkha Rifles Battalion and the Mercian Regiment under my command. The ‘Conspicuous Gallantry Cross’ is not bestowed casually, it was a most noteworthy achievement by that particular young Gurkha.’

“Better to die than be a coward” is the world-famous motto of Nepalese Gurkha soldiers, who have been an integral component of the British Military.

Kukri

The Kukri, an 18-inch long curved knife, which is the Gurkha’s traditional weapon is still carried into battle today. For centuries, it has been said that once a Kukri is drawn into battle, it had to “taste the enemy’s blood” – if not, its owner had to cut himself to draw blood before returning it to its sheath. Now, the Gurkhas say, cooking is the Kukri’s main use.

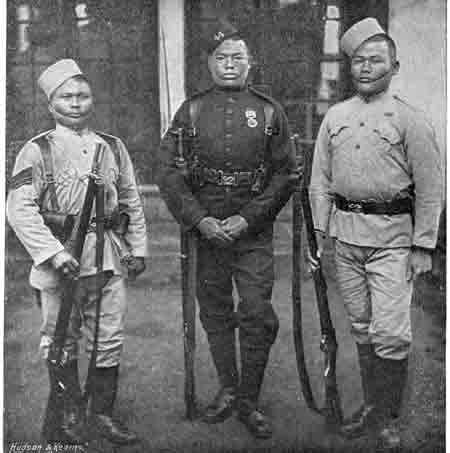

The potential of these fierce, brave warriors was first realized by the British during the height of their empire in the last century. After enduring substantial casualties during the invasion of Nepal, the British East India Company signed a peace treaty, quickly put together in 1815, which also allowed the British to recruit soldiers from the forces of the former enemy.

Following the independence of India in 1947, an agreement between Nepal, India, and Britain meant that four Gurkha troop regiments of the Indian Army were transferred to the British Army, ultimately becoming the Gurkha Brigade. Since then, the loyal Gurkhas have fought all over the world for the British, receiving 13 Victoria Crosses among them.

More than 200,000 Gurkhas fought in World War I and II and in the past 50 years they have served in Kosovo, Cyprus, Malaysia, Hong Kong, Borneo, the Falklands, and now in Afghanistan and Iraq. The Gurkhas serve in a variety of roles, mainly in the infantry, but there are also significant numbers of signal specialists, engineers, and logisticians.

Gurkha

The name “Gurkha” is attributed to the town of Gorkha from which the Nepalese realm had developed.

The Gurkha troops have always prevailed with four indigenous groups, the Rais and Limbus from eastern Nepal, who live in villages on impoverished hillside farms and the Gurungs and Magars from central Nepal.

They retain their Nepalese customs and beliefs, and the brigade participates in religious festivals such as Dashain, in which – in Nepal, not the UK – goats and buffaloes are sacrificed. The Gurkha Brigade numbers have been in a sharp decline from the World War II peak of 112,000 men and now stand at only 3,500.

During the two World Wars, 43,000 men met their death. The Gurkha Brigade is now based at Shorncliffe near Folkestone, Kent – but they cannot become British citizens. The troops are selected from the young men living in the hills of Nepal. Each year, approximately 28,000 Nepalese youths challenge the selection process for a little over 200 positions. The selection procedure has been depicted as one of the most difficult in the world and is fiercely contested. The_gurkha_hat_49 Young hopefuls have to run for 40 minutes uphill carrying a wicker basket filled with rocks weighing 70lbs on their back.

Prince Harry stayed with a Gurkha battalion during his 10-week assignment in Afghanistan. There is said to be a cultural kinship between the Gurkhas and the Afghan people, which is quite valuable to the British Army’s effort there. Historian Tony Gould said Gurkhas have, from a military point of view, brought an outstanding combination of qualities. He said: “They are tough, they are brave, they are durable, and they are amenable to discipline.”