In the modern world, it is unusual for a general to become the leader of an important nation. Political and military leadership have become two different career paths, requiring different skills and experience. At other times, for example in Sengoku Jidai Japan or feudal Europe, military and political leadership have been tied together – to rule in peace required that a leader also commands during the war.

Between these periods exist a different sort of leaders – ones who turned their fame as generals into political power.

Julius Caesar

First-century Rome was in a state of transition. A republic governed by its senatorial class, it controlled an increasingly large empire. As its territory expanded, it became harder for bickering politicians with no single leader to successfully govern.

At the same time, success was fuelling the ambition of generals, men drawn from the senatorial class. Three of them – Crassus, Pompey and Caesar – combined their efforts to dominate politics from 60 BC to 53 BC, when Crassus died and Pompey allied himself with the more conservative senate.

Successes in Gaul and Germany made Caesar popular with the people and the army. The senate, seeking to curb his power, ordered him to disband his troops. Instead, he broke Roman law by marching them into Italy, across the barrier of the Rubicon River, in 49 BC. Civil war followed, ending with a victorious Caesar effectively ruling Rome.

Romans had long feared the dictatorial influence of kings, and so Caesar never took on the title of king or emperor. His political reforms, together with the unresolved conflicts of his rise to power, led to his assassination in 44 BC.

Oliver Cromwell

A member of England’s 16th-century gentry, Oliver Cromwell would have lived a life of obscurity if not for the English Civil Wars. A Puritan and political reformer, he sided with Parliament against King Charles I. When war broke out in 1642, Cromwell raised a cavalry troop. Despite his only previous experience being in local militias, Cromwell proved an excellent commander, leading the cavalry in successful campaigns across East Anglia and rising in rank through the Parliamentary army.

Such was Cromwell’s success that he was the only commander not forced to choose between political and military rank during parliamentary reforms. He was one of the men responsible for rebuilding Parliament’s forces as the New Model Army and for Charles I’s defeat and eventual execution.

Following Charles’s execution in 1649, the country struggled to form a stable government, as Parliament, the army and rabble-rousing radicals grappled for power. After a succession of failed governments, Cromwell was made the new head of state as Lord Protector in 1653.

Cromwell ruled for five years in an increasingly monarchical style. Unlike Caesar, his dynasty would not long outlive him. His son Richard became Lord Protector, but was too weak to retain control of the country, and the monarchy was soon restored.

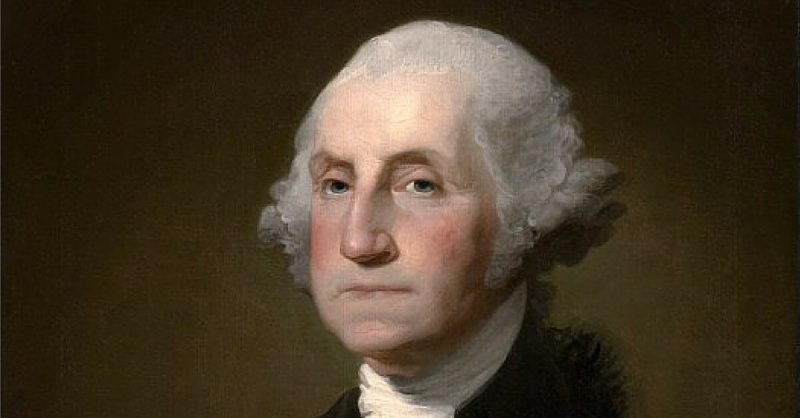

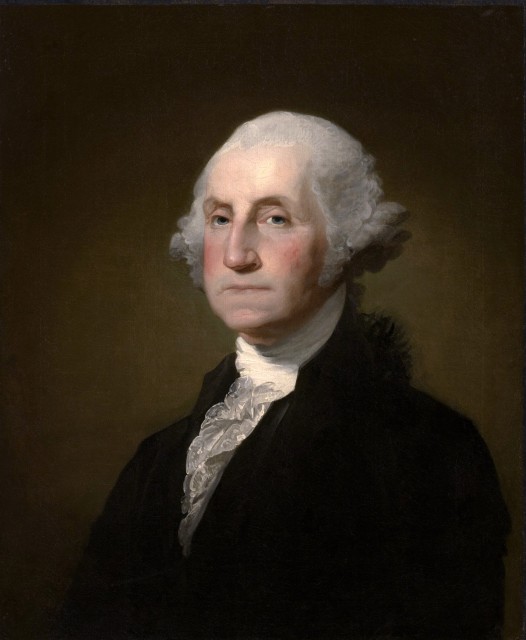

George Washington

The son of a family of wealthy planters, from early in his life George Washington showed a gift for command. During the French and Indian War, he fought for the colonial militia, becoming a senior officer in what were then the British colonies in America.

When the American Revolution came, Washington was among the leading politicians calling for independence. Thanks to this experience, prestige, charisma and patriotism, he was made commander-in-chief of the Continental Army in 1775. As well as commanding in the field, Washington was responsible for organising and training the army of the new nation. He became the poster boy for the revolutionary cause and a symbol of its success.

Given his status, it was no surprise when Washington was unanimously elected the first President of the United States of America in 1789. Over eight years, he helped to unify the new nation, easing tensions within it. He retired from politics in 1797 and died in 1799, still America’s greatest hero.

Napoleon Bonaparte

A minor French noble from Corsica, like Cromwell, Napoleon might have lingered in obscurity if not for his nation’s revolution. Unlike Cromwell, he was a trained military officer and one who proved flexible in his political ideals.

Napoleon rose to prominence as an artillery officer during the wars that followed the French Revolution, as the newly republican government sought to spread its ideals across Europe, and other nations sought to crush these dangerous ideas. He played a leading part in the siege of royalist Toulon in 1793, and in 1795 saved the government from destruction when he turned cannons on a Parisian mob. Successful campaigns in Italy made him a national hero.

Republican French politics was a mess of coups and plots. It was through such a coup that Napoleon made himself First Consul, the head of the nation, in 1799, with the backing of the army and key politicians. He conquered half of Europe in a string of famous campaigns and made himself Emperor of the French in 1804.

Against the combined power of the other European nations, Napoleon was finally defeated and overthrown in 1814. He returned in 1815, was defeated one final time at the Battle of Waterloo, and spent the rest of his life in exile, dying in 1821. Despite his eventual failure, his rule would always be remembered as a period of great glory for France.

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington

Napoleon’s most famous adversary, the Duke of Wellington started out as Arthur Wellesley, a career soldier from Protestant Ireland. A great defensive commander, he served with distinction in the British colonies, rising to the rank of general. Returning to Europe, he led British forces in the Peninsula Campaign, during which he drove the Napoleonic French out of Portugal and Spain. For this success, he was made Duke of Wellington in 1814, and in 1815 he led the British to victory against the returned Napoleon at Waterloo.

Now a member of the House of Lords, Wellington became active in politics. He was Prime Minister from 1828-1830, and again briefly in 1834. By this time the British monarch was essentially a figurehead, with the Prime Minister running the country.

Wellington was not a popular leader. His extreme conservatism offended reformers while his support of Catholic emancipation alienated many conservatives. Though he held other political posts prior to his death in 1852, he did not get to spend long in charge of the country he had fought to protect.

Sources:

- Charles River Editors (2014), Oliver Cromwell.

- Ellis, Geoffrey (1991), The Napoleonic Empire.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian (2003), In the Name of Rome.

- Keegan, John (1987), The Mask of Command.