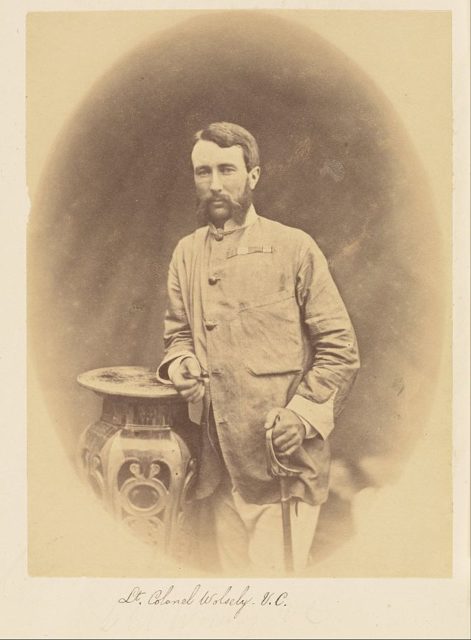

Sir Garnet Joseph Wolseley was one of the most important military thinkers in the Victorian British army. Rising to a position of prominence in the last 19th century, his fine military service, and reforming zeal eventually earned him the title of Viscount Wolseley. But it was a career marred by controversy, and whose results were limited by others.

1. Promotion by Merit

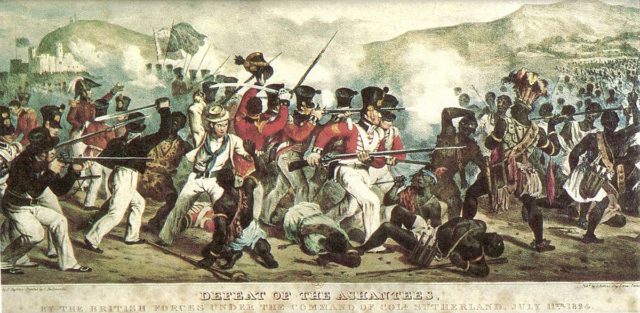

Wolseley was a rare creature in the Victorian military establishment – a man promoted thanks to merit, not money or credentials earned at the Staff College. His early career saw him serving all over the Empire, from Burma to China to the Crimea. Twice injured in battle, he lost the sight in one eye and was repeatedly mentioned in dispatches for his courage and competence. He led successful expeditions to Red River in Canada (1870) and in the Ashanti War in east Africa (1873-4). He also commanded troops in the Zulu War and annexed Egypt for Britain following the defeat of nationalist forces at Tel-el-Kebir in 1882.

As well as earning praise as a field commander, Wolseley served in administrative positions in South Africa and Cyprus. His was a well-rounded and largely successful career which earned him the nickname “Our Only General” and made the phrase “all Sir Garnett” a symbol of efficiency.

Despite his various successes, Wolseley’s field career ended with tragedy. Leading the relief forces marching on Khartoum in 1884-5, he was too late to save the city from Mahdists, leading to the death of the British commander there, Major-General Gordon, and his troops.

2. Reforming Ideas

Wolseley was a student of war, who wrote up his reflections in The Soldier’s Pocket-Book, published in 1869. This emphasized the need in times of peace to prepare for war.

Gaining his first position at the War Office in 1871, Wolseley pushed a reforming agenda, trying to modernize the British army. He wanted to bring in shorter periods of service, reforms in the relationship between regular and auxiliary forces, and other fundamental changes. In preparing his own expeditions he relied upon elite units, well prepared and equipped.

The Victorian army was built around an ideology of superior moral character, the idea that strong spirit and esprit de corps were the keys to victory. Wolseley did not deny the importance of this, but he believed that short service need not undermine fighting spirit and that other factors were at least as important in achieving victory. This brought him into conflict with others in the establishment.

3. The Wolseley Ring

To support his reforming agenda and ensure that he was working with the best of the best, Wolseley built up a group of like-minded and talented officers, referred to as the Wolseley ring. Made up primarily of fellow Red River officers, other distinguished veterans and promising Staff College graduates, the ring was a talented group.

By repeatedly using the same men, Wolseley was able to reinforce and develop his ways of working, and ensure command continuity in his operations.

The ring provoked controversy within the army. By favoring a particular group of officers, Wolseley largely excluded others from service under him, and therefore from significant expeditions such as his campaign in Egypt and the ill-fated attempt to relieve Khartoum.

4. At the War Office

Wolseley first served in the War Office, the institution that oversaw the running of the army, in 1871. Following the failure of the Khartoum expedition in 1885, his only service in the field was a brief stint commanding the army in Ireland. Other than this, he now served as a guiding hand for the British military.

He was Adjutant-General from 1882 to 1890, during which time he pushed for improvements in the diet and clothing of ordinary soldiers, including a move away from brightly colored uniforms. He modernized the infantry drill book, supported the expansion of the military intelligence service, and was among those calling for more military resources and better preparation for home defense.

In 1895 he became Commander-in-Chief. He continued to push for modernisation, professionalism and greater resources for the army. But his efforts were limited by ill health and his poor relations with key politicians. He stepped down at the start of 1901.

5. Relationship with the Duke of Cambridge

Wolseley’s reforming efforts were often undermined by Prince George, the Duke of Cambridge, who was commander-in-chief from 1856 until 1895. A cousin of Queen Victoria, the Duke’s position in command of the army was virtually unassailable, despite growing signs that he was a poor choice for the job. Serving under him was a defining feature of Wolseley’s career.

Cambridge was a staunch conservative who repeatedly opposed military reforms. He believed that Britain’s successes proved the army’s efficiency, and there was no need for change. He and Wolseley represented opposing viewpoints within the army, one the stick-in-the-mud aristocrat representing the establishment, the other the up-and-coming reformer. Many of Wolseley’s ideas were blocked or limited by Cambridge’s influence, and the two men are widely remembered as bitter opponents.

Yet Cambridge and Wolseley also found common ground. Together, they called for more resources to be funneled into the army so that it would be better prepared for a European war. They saw themselves as servants of the Crown and resented the way politicians interfered in their work, while never challenging the legitimacy of those politicians’ authority. They both worked to gain control of the military supply chain from civilians.

6. Anti-climax or Groundwork?

Wolseley never achieved the great possibilities he saw in the British army. The efficient despatched of troops to South Africa in the late 1890s seemed to vindicate his work, but was undermined by the appalling performance of commanders in the field. His reforms, so long thwarted by Cambridge, never reached their full potential.

By laying the groundwork for military reform, Wolseley counteracted some of the conservatism inherent in an army run by the aristocracy. He died in 1913, so never saw the ultimate test of his reforms and the ultimate demonstration of their limits – the First World War.