Massed professional armies do not always win wars. Irregular troops sometimes win; whether volunteer forces or specialists trained in unconventional ways of war. They are fought with deceit, outwitting their opponents.

These are eight wars where irregular forces brought trained armies to grief.

Spain and the Birth of Guerrillas

The term “guerrilla warfare” comes from the Peninsular War (1807-1814).

Napoleon used a combination of political and military maneuvering to take control of Spain and place his brother on the throne. It was unpopular with many Spaniards, who attacked the occupying forces and supported the British as they arrived to fight Napoleon. Attacks by irregulars were often brutal, as were the reprisals against them, which included massacres by French soldiers.

The word “guerrilla,” meaning “little war,” entered the English language through the troops who heard it in the Peninsula.

The Haitian Revolution

The Haitian Revolution (1791-1804) was unique in being a revolution which was both successful and not driven by the desires of the middle class.

This massive slave uprising saw the inhabitants of Saint-Domingue throw out the colonial French and cast off white slave-owners. In a reversal of the usual pattern, the irregulars were massive armies of freed slaves, rather than small bands fighting a guerrilla war. The bitterness caused by slavery resulted in brutality and destruction on both sides. The death toll was immense.

After throwing out their colonial masters, the rebels founded the nation of Haiti. It shocked the established powers of Europe.

The Thousand in Italy

Giuseppe Garibaldi’s campaigns to unite Italy were always fought using irregular forces. He was a nationalist relying on volunteer patriots to form the armies with which he turned the country upside down.

The expedition of the Thousand to Sicily (1860) was the most remarkable of these campaigns. Outnumbered 25 to one, Garibaldi’s redshirts beat the professional armies of the Kingdom of Naples in a series of small battles. Always on the offensive, Garibaldi created fear in the Neapolitans out of all proportion to his might. When they called for a truce, they still outnumbered him five to one, despite the Sicilians who had flocked to his side.

With Sicily taken, Garibaldi crossed to the mainland. He captured the Kingdom of Naples, riding into the city on a train with a small band of his soldiers. He had united most of Italy.

The Second Boer War

The Second Boer War (1899-1902) was not a victory for irregular troops, yet it is still remembered as a triumph for irregular tactics.

The war began with Boer successes that shocked the British Empire. The British responded by bringing in professional armies. They marched across the Republic of Transvaal and the Orange Free State, forcing the Boers into retreat.

The Boers then took to guerrilla fighting. Sharpshooters and careful use of the country caused considerable damage to the British, even when the Boers were forced to withdraw. Incompetent leadership added to British woes. Ongoing guerrilla fighting forced the British to set up block houses and run vast stretches of wire fencing across the wilderness to limit Boer movement.

Although the British ultimately won, it was a painful victory and one from which they learned many lessons about how not to fight.

East Africa in the First World War

The British faced a similar situation in East Africa during the First World War. Here, the German Colonel Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck realized he would be vastly outnumbered. Rather than stand and fight, he reorganized his army into one using ambushes and raids. He then set up supply chains and retreated into the bush.

The British pursued him with their superior numbers, including South African troops that had previously fought against them. The British General Jan Smuts, a Boer veteran, led the most successful campaign against him, using maneuver rather than brute force. For the whole four years of the war, the British were never able to capture Lettow-Vorbeck. His raids and supply thefts were a constant thorn in their side.

Burma in the Second World War

The roles were reversed for the British in Burma during World War Two. Here, driven back by Japanese offensives, they adopted the tactics of guerrilla warfare.

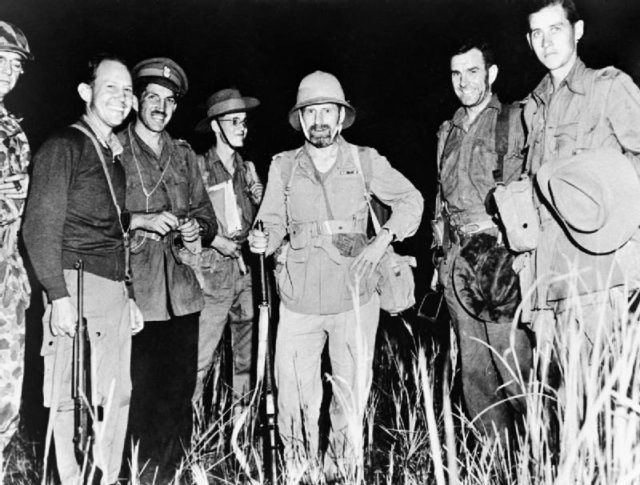

Some of this was done by raising trouble locally. Hugh Seagrim and others like him recruited networks of guerrilla fighters from the Burmese opposed to Japan.

The British also trained some of their own troops for guerrilla warfare. Successfully led by Orde Wingate, these forces parachuted behind Japanese lines to attack their supplies and communications. Wingate developed a strategy of setting up strongholds in the Japanese-held jungle, from which commando raids could be launched.

Vietnam

Vietnam was shaped by two wars in which irregular forces defeated expensively equipped foreign armies.

First came the Indo-China War (1950-1954), in which the Vietnamese defeated the colonial French. It climaxed in the Battle of Dien Bien Phu, where the Vietnamese used bicycles to move supplies and artillery up hillsides, surrounding the French. Unable to effectively use their tanks in the dense terrain, cut off from supplies, the French were defeated.

Then came the Vietnam War (1955-1975). Again, the North Vietnamese relied on guerrilla tactics, ambushing the South Vietnamese and their American allies. Traps, deception, and tunnel networks all played a part. Although America flung its industrial might and immense firepower into the war, it could not defeat the guerrilla tactics and strategic maneuvering of General Giap.

Sources:

Gordon Brown (2008), Wartime Courage.

Mike Duncan (2013 onwards), Revolutions Podcast.

Philip Haythornthwaite (2004), The Peninsular War: The Complete Companion to the Iberian Campaigns 1807-14.

Richard Holmes, ed. (2001), The Oxford Companion to Military History.

Geoffrey Regan (1991), The Guinness Book of Military Blunders.

David Rooney (1999), Military Mavericks: Extraordinary Men of Battle.