Early Armor

Throughout history, soldiers have sought new ways to protect their bodies from the weapons of war. As armament technology was developed, so to did armor. As with many early technologies, it is not known when and where armor was first implemented. It is likely many different people in many different countries found ways to clothe themselves against harm.

Non-metal armor rotted over time, leaving no physical remains. Later examples and illustrations, together with studies by anthropologists, point towards the possibilities. Leather was probably one of the earliest materials used for armor and remained popular down the millennia thanks to its durable and flexible nature.

Layers of cotton or other cloth provided padding against blunt attacks but could be vulnerable to sharper weapons which developed with the use of metalsmithing. Wood has even been used for armor in some places, for example by the Siberian Chukchi people.

Shields

The shield was also one of the earliest developments in armor. Being carried rather than worn had advantages and disadvantages. On the downside, a shield took up a hand making it useless for troops with two-handed weapons such as long spears or bows.

On the upside, if penetrated by an arrow or spear a shield might prevent it from piercing the body. It could be moved around to protect different areas, including the face.

Shields were vital to ancient Greek infantry, who were named hoplites after their shields or hoplons.

Adding Metal

Once people learned to work metal into weapons, they realized it could also be used for armor. One of the earliest images of armor, on the Royal Standard of Ur, shows Sumerian soldiers wearing copper helmets and leather cloaks covered with metal disks.

Helmets were a significant development as they offered protection to the head, a vulnerable and vital spot often hit by swinging weapons. Stitching metal onto cloth or leather did not provide reliable protection all over, but it meant there was a chance of deflecting a bladed weapon.

Warriors in partially metal armor were much less vulnerable than their opponents.

Lamellar

Metal on cloth led to scale armor, in which the metal pieces overlapped each other for better coverage. The natural next step from this was lamellar. Lamellar was armor made up entirely of pieces of metal, connected with cords or wires. It could create strong and flexible results and did not require the advanced smithing which would lead to full plate armor.

The Romans primarily wore chainmail. During their heyday, many legionaries dressed in lamellar and this is the armor with which they are most associated.

Chainmail

Chainmail, which existed alongside lamellar and scales armor, was invented by the Celts. Made up of thousands of interlocking rings, it was more flexible than lamellar.

It offered excellent protection against slashing weapons and when worn with padding underneath could spread the force of a severe blow. Chainmail, however, was less effective against stabbing weapons, which could pry through a gap in the links.

Chainmail spread across Europe, Africa, and Asia. It was sometimes combined with small plates of armor and was often worn with a helmet. In the slashing combat of medieval Europe, it was the best available armor for several centuries.

Plate Armor

Plate armor made from bronze existed in ancient times. The softness of bronze meant it was abandoned when iron weapons and armor came to the fore. For centuries, iron was more effective than bronze but could not be worked in large enough pieces to make plate armor.

By the fourteenth century, European smiths learned how to work iron and the tougher metal, steel. Able to offer greater protection against arrows and crossbow bolts that penetrated chain mail, plate armor became popular among the wealthy.

Entire suits of it were produced in the 15th and 16th centuries, with increasingly sophisticated joints.

The Decline of Armor

The growing power and popularity of guns gave ordinary soldiers a weapon capable of piercing even the toughest armor. As musketry became the mainstay of European armies, metal armor stopped being a viable piece of equipment for most troops.

In the 17th century, cavalry and pikemen continued to wear breastplates and helmets. By the end of the century, however, bayonets had replaced pikes, turning every infantryman into a musketeer. Armor fell by the wayside.

The Return of Helmets

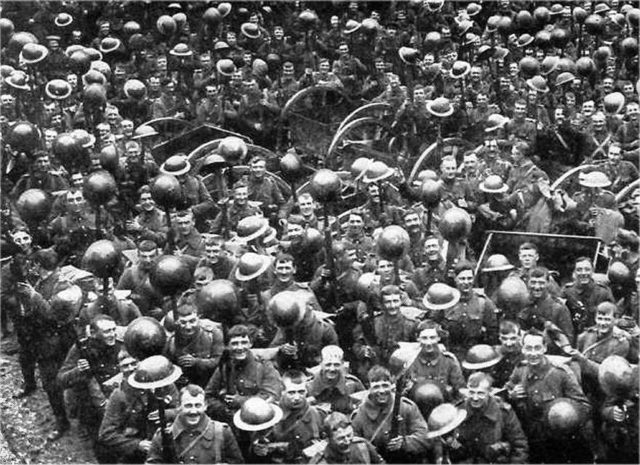

200 years later, the First World War saw a resurgence in armor. With trench warfare, soldiers’ heads were often the only part of the body exposed to enemy fire. Shrapnel from exploding shells, bombs, and grenades contributed to a huge number of fatal head wounds. Armies adopted a broad range of different styles of steel helmets. The German design gave excellent protection to the neck as well as the head.

Experiments with all-covering armor were undertaken. The Germans dressed many machine gunners and snipers in a steel corselet and helmet. Covering everything but the eyes, it gave them a disturbingly dehumanized appearance.

Flak and Modern Body Armor

In World War Two, armor came full circle, with a return to flexible non-metal materials. Bomber crews, vulnerable in their large, slow planes, were given flak jackets as protection from the flying fragments of anti-aircraft shells.

By the later stages of the Korean War, the infantry was equipped with nylon vests that could stop shell fragments and pistol bullets but not shots from rifles. These continued to be used in Vietnam. By the First Iraq War, Kevlar had come into use. A light synthetic material stronger than steel, it is often combined with hard plates to provide protection against modern weapons.

Armor is back in fashion and looks set to remain so for a long time.

Source:

- John Keegan and Richard Holmes (1985), Soldiers.

- William Weir (2006), 50 Weapons that Changed Warfare.