The ship was named the Temeraire from the French téméraire which means bold, reckless, or rash. The actions of the ship’s crew might indeed have been reckless – but against the French in one of the greatest naval battles in history.

Construction

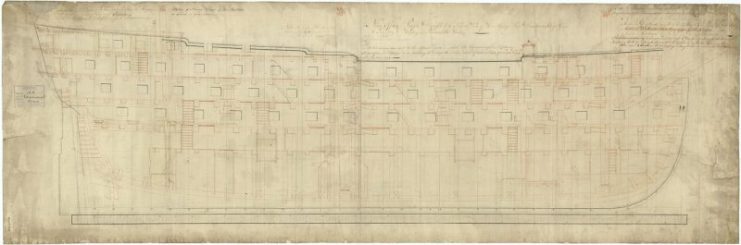

Laid down at the Chatham Dockyard in July 1793, it took the Royal Navy five years to build the 98-gun second-rater. When Temeraire was launched on September 11, 1798, the ship was a thing of beauty.

At 185 feet in length and 51 feet abeam, the full-rigged ship of the line was just over 2,100 tons and one of only three ships of the Neptune class. It was armed with cannons and also carronades — artillery that could wreak such havoc at short range that they were nicknamed “smashers.”

Its hull was made from over 288,000 cubic feet of oak, mostly from the Hainault forest of Essex. That hull was clad with 3,900 sheets of copper to extend the service life of the ship.

Temeraire’s first commissioning came on March 21, 1799, to join the Channel Fleet. With the war against Napoleon Bonaparte raging, the ship took part in tedious blockade duties.

By late 1800, the ship had seen little action, having switched commanders on several occasions. It was assigned dull work, and many of the crew had been in the service for several years.

Mutiny

The only notable action that the Temeraire had at this time was a mutiny. In 1801, the Second Coalition against Napoleon had collapsed. Peace was in the air and would be realized, albeit temporarily, when the Treaty of Amiens was signed in March 1802.

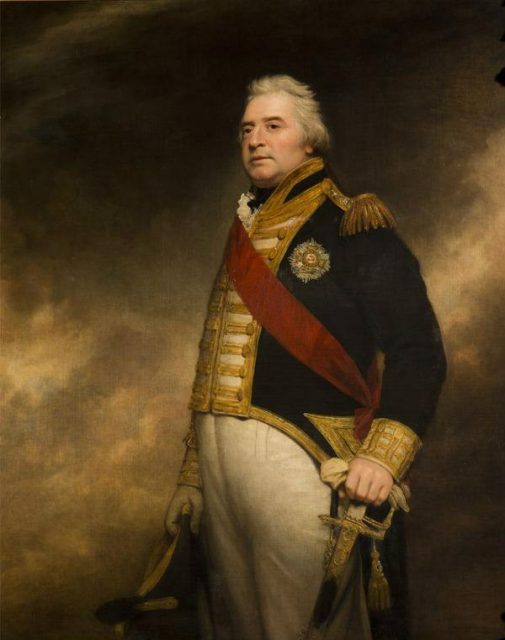

However, in December 1801, Temeraire was acting as the flagship for Rear Admiral George Campbell and was standing in Bantry Bay off the southwest coast of Ireland.

The crew wanted to go home, but they had heard a rumor (which was correct) that the ship was to be sent to the West Indies to consolidate British holdings. The crew resented this and, on December 3, demanded to know where the ship was going.

Admiral Campbell refused to disclose any details, instead informing the men that in the past officers had never told the crew where a ship was going. The crew then stated they would not raise anchor unless they were to sail for England.

Campbell was adamant and sent the crew below decks. The mutiny seemed to have been quashed, but the dozen or so ringleaders began working behind the scenes and organized a group of up to twenty men who then recruited more men, including marines.

Soon enough, the mutineers closed the gun ports, jeered at the officers, and refused to obey unless their demands were met.

A standoff occurred over the fate of a marine named McEvoy who was to be punished for insolence. The officers seized McEvoy and put him in irons. The mutineers called out to the crew to rise up but found that the marines were standing with the officers.

After a few tense minutes, the ringleaders were arrested and hanged, and peace returned to Temeraire.

Trafalgar

If nothing but mutiny had occurred aboard Temeraire, then the ship would have been an obscure footnote in history. However, the Battle of Trafalgar changed all that and indelibly placed the ship and its crew into the annals of naval history.

The Peace of Amiens ended in May 1803, and hostilities between the French and the British renewed. Napoleon was determined to invade the British Isles. The British continued their blockades of French ports to deny Napoleon the opportunity to do this.

Temeraire, this time under the command of Captain Eliab Harvey, joined the Channel Fleet in December 1804 to carry on the arduous duty.

However, Spain had allied with France and declared war on Britain. Napoleon now had at his disposal a combined fleet of 102 ships of the line compared to Britain’s eighty-three.

This set the stage for a showdown which took place on October 21, 1805, when the French and Spanish attempted to break the British blockade off Cadiz, Spain at Cape Trafalgar.

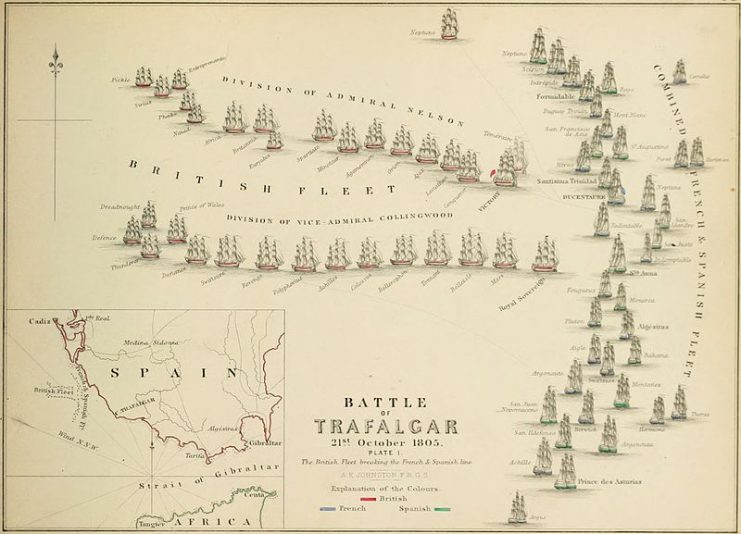

The Order of Battle

Typical strategy of the day was to form the line of battle parallel to one’s opponent. However, against strategic orthodoxy, British Admiral Lord Horatio Nelson developed a plan to cut the enemy’s line of battle by sailing into it head-on in a two-column formation.

The British were outgunned and outmanned at Trafalgar. Nelson had 27 ships of the line under his command ranged against 33 under the command of the French Vice-Admiral Pierre-Charles Villeneuve. But the British sailors had more experience since the French fleet had been trapped in port, idle.

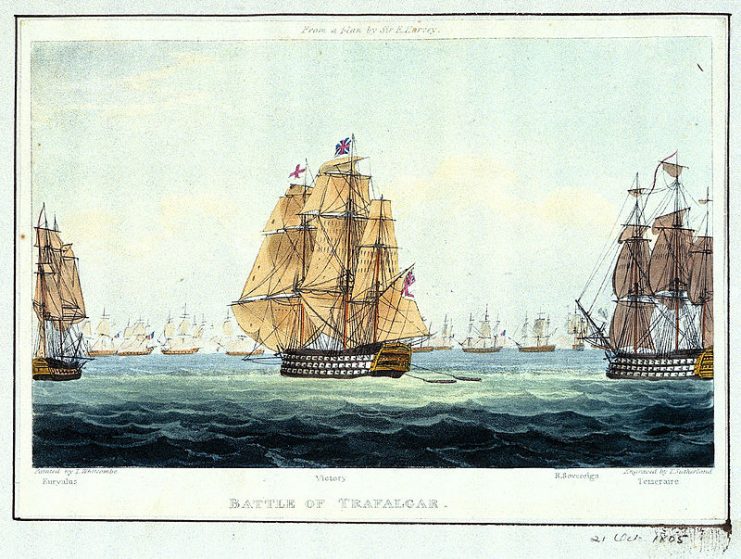

Nelson in his flagship, Victory, led the attack against the enemy line. It was a slow charge since the winds were light, which allowed ample opportunity for the French and Spanish to fire raking shots against the British ships.

Behind Victory came Captain Harvey’s Temeraire with some 720 men. It was slightly undermanned since the ship’s full complement was 738.

Temeraire, like the rest of the British fleet, was under full sail. This, too, was against orthodoxy since sails were likely to be damaged by fire, and it was thought best not to have them at full sail. Temeraire raced ahead and started to overtake Victory.

When Lord Nelson’s friend Henry Blackwood saw Temeraire coming up, he suggested to Nelson that he should let Temeraire take the lead to reduce the personal danger to his lordship. Nelson had become a symbol of British naval power and patriotism, and he was a talisman.

Initially, Nelson agreed, but when Admiral Collingwood, who led the second column against the French and Spanish, would not drop to the second position in his line, Nelson changed his mind. Meanwhile, Temeraire had gained on Victory.

Nelson promptly signaled to Captain Harvey, “I’ll thank you, Captain Harvey, to keep in your proper station, which is astern of Victory.” Harvey stayed close behind Victory as they entered into battle.

Temeraire’s Finest Hour

Harvey’s first move was to sail for Nuestra Señora de la Santísima Trinidad, the flagship of Rear Admiral Baltasar Hidalgo de Cisneros, which was second in the line to the Villeneuve’s Bucentaur which Victory was engaging.

Santísima Trinidad was the largest ship in the world at that time, being a four-deck monster of almost 5,000 tons and 130 guns. It lumbered in the water, its great bulk making it slow in the light winds.

Temeraire fired at Santísima Trinidad as well as any other ship that drew near for the next 20 minutes. The smoke grew so thick that Captain Harvey thought that he might be firing on Nelson’s Victory which he could not see.

When the smoke started to lift, Harvey saw Victory in close combat with the French 74-gun Redoutable, one of the best ships in the French fleet. Victory was taking heavy fire, and a musket ball had pierced Lord Nelson’s spine.

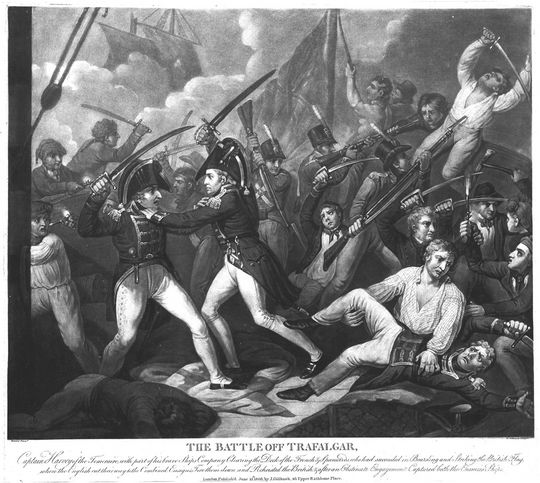

The captain of Redoutable, Captain Jean-Jacques Lucas (who was cut from the same cloth as Nelson), attempted to board the larger ship. However, he was having difficulty maneuvering into position to move his men en masse. Nevertheless, grapnels were being attached to Victory.

Harvey then brought Temeraire about and crossed the stern of Redoutable, blasting it with shot. Captain Lucas would later write, “It would be difficult to describe the horrible carnage caused by the murderous broadside of this ship; More than 200 of our brave lads were killed or wounded.”

Lucas himself was wounded by the shot.

Then Harvey rammed Redoutable, dismounting French guns in the process. The British lashed their ships together and close fighting began. The crew of Temeraire surged across.

In the mayhem, grenades were lobbed from the rigging, with one coming into the powder screen and exploding. The master of arms prevented a fire from getting to the munitions which would have destroyed Redoutable, Victory, and Temeraire.

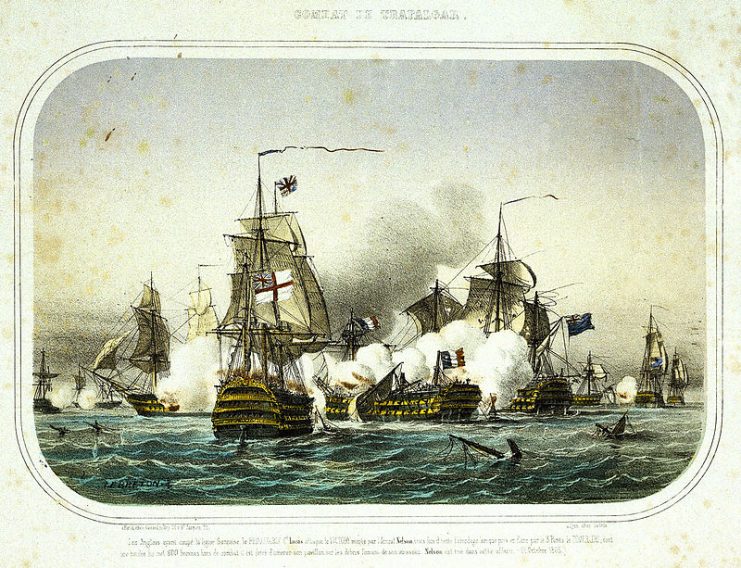

Meanwhile, the Spanish Santa Ana fired multiple broadsides into the Temeraire’s stern. To make matters more alarming, a French 74-gunner named Fougueux swept in to aid Redoutable.

Temeraire was withstanding heavy damage with the worst done by the mainmast of Redoutable, which fell atop Harvey’s ship. This did have a silver lining since it allowed the British to cross more easily to Redoutable to take her.

Eventually, when it was clear that Lucas’s ship would sink with a great loss of life if he did not give up, the French captain surrendered his sword.

Meanwhile, Harvey had been watching Fougueux drift closer and closer. The captain of the French ship had thought that Temeraire was too engaged in the battle with Redoutable to notice him. But Harvey had been waiting. His starboard guns had not been fired yet, and the gun crews were fresh.

With a blast of her guns accompanied by small arms fire, Temeraire hammered Fougueux with a double shot, driving her crews below decks. They soon came out with swords and axes. But Temeraire was a taller ship, and Harvey’s marines pinned down the crew of Fougueux.

The British then lashed the French ship to Temeraire. Harvey’s ship was now sandwiched between Redoutable and Fougueux. Harvey’s first lieutenant, Thomas Kennedy, led his men aboard through the ports and from the chains.

Not long after, the French captain was shot through the heart, but the French fought on, defending their ship as best as they could. But they were soon overwhelmed, and the second in command surrendered Fougueux.

Captain Harvey’s Temeraire had saved Lord Nelson’s Victory (though not Nelson) and captured two prizes of which Redoubtable was considered one of the best the French had.

Temeraire itself was terribly damaged. The sails lay in tatters. Every yard had been destroyed, and the lower masts were the only ones left standing. Forty-seven of the crew had perished, and 76 were wounded

Temeraire was helpless and was towed off the line by Sirius. But the battle wasn’t quite over as French ships that had not yet engaged opened fire upon Temeraire. The British ship opened fire in response, and the French soon slipped away.

Immortalized in Art

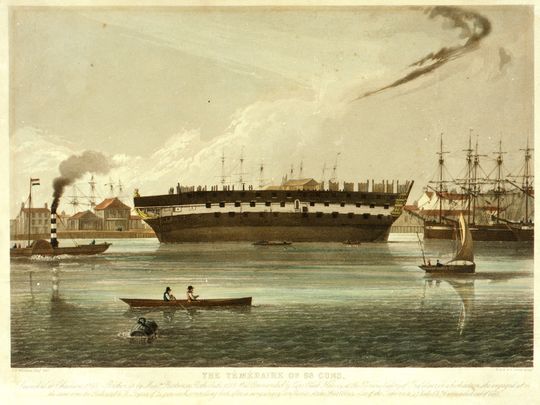

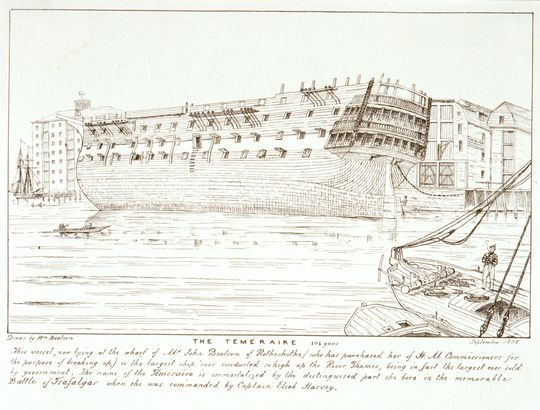

The Battle of Trafalgar was the only fleet action that Temeraire ever saw. It was subsequently repaired and served in the Baltic and Mediterranean. The ship was retired, then served as a prison hulk from 1813 to 1819. It then became a receiving ship followed by duty as a victualling depot in 1829, its fighting days long past.

Its final duty was as a training ship until it was sold in 1838 and broken up.

Read another story from us: “I See No Ships” Facts You May Not Have Known About Horatio Nelson

But the legacy of Temeraire carried on, and the ship was immortalized in J.M.W. Turner’s painting The Fighting Temeraire Tugged to Her Last Berth to Be Broken Up. The painting, which captures the warship on its last voyage, is critically acclaimed as capturing the spirit of the dying age of sail.

Interestingly, it was Turner who nicknamed the ship “Fighting Temeraire.” Before that, it was usually called “Saucy Temeraire.”

Today, the painting may be found in the National Gallery in London.