“We had targets set up and fired two separate test rockets while we were there to measure the amount of damage they could inflict on enemy forces.”

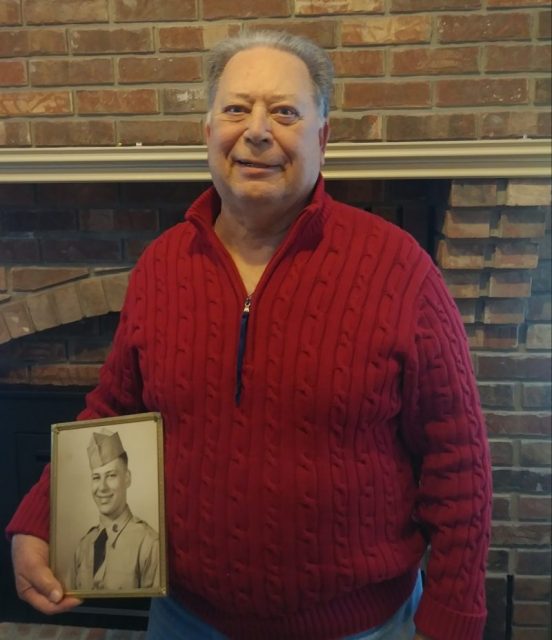

As a first generation citizen of the United States, Dennis Oppenheim learned at an early age that opportunities might present themselves in the most unexpected fashion. Raised by Danish immigrants in the bustling city of Chicago, he soon discovered the valuable lessons provided to him through service in the Cold War-era armed forces.

“I started high school in Chicago in 1953 but decided to quit school in 1955 and went to work for a year,” Oppenheim recalled. “On my eighteenth birthday [March 1956], I was required to sign up for the draft but decided to enlist in the U.S. Army the following month,” he added.

As the veteran explained, the Army offered a three-year enlistment period whereas the Navy and Air Force required a new recruit to commit to a term of four years.

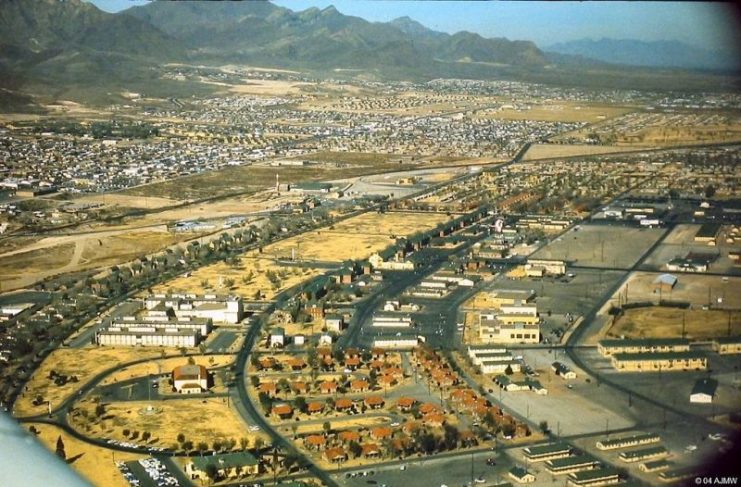

Shortly after signing his enlistment papers in April 1956, he boarded a bus for Fort Leonard Wood to complete eight weeks of basic training. Upon graduation, he was granted twelve days of leave to return home before reporting to his next duty assignment at Fort Bliss, Texas.

“They placed me in the 550th Field Artillery Battalion and I started out training as a launcher crewman with the ‘Honest John’ rocket,” Oppenheim said. The MGR-1 Honest John was a nuclear-armed surface-to-surface rocket developed in the early 1950s and later adapted to use conventional and chemical warheads. It is considered the first tactical nuclear weapon of the U.S.

Following Oppenheim’s arrival at the Texas base, the decision was made to convert his military occupational specialty to that of atomic warhead specialist and he was sent to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, to learn the skills associated with his newly appointed duty assignment.

“It was supposed to be a four-week course that they crammed into two weeks,” he said. “In order to launch the rocket, you have to complete a sequence of steps using boxes with switches and lights. During the training, we had to demonstrate that we were able to complete the entire launch sequence in five minutes.”

The young soldier returned to Ft. Bliss for a number of months to continue refining his skills as part of a rocket crew; however, his battalion was then sent to White Sands Proving Grounds in New Mexico, where they spent approximately nine months performing launch exercises.

While in New Mexico, he was able to finish the high school studies he had deserted a few years earlier by earning his GED. Once the battalion returned to Ft. Bliss from their training at White Sands, there was little down time to be enjoyed since Oppenheim and a small group of soldiers was sent to Fort Bragg, North Carolina, for a unique training assignment.

“They sent us to Fort Bragg to make a training film for the airborne troops to demonstrate the use of the ‘Little John,’” Oppenheim said. The MGR-3 Little John, he explained, was a smaller artillery rocket system designed for deployment in airborne assault operations.

Weeks later, he returned to Ft. Bliss but the battalion was soon on their way to the country of Panama for another unexpected opportunity—the testing of a new warhead design for the Honest John.

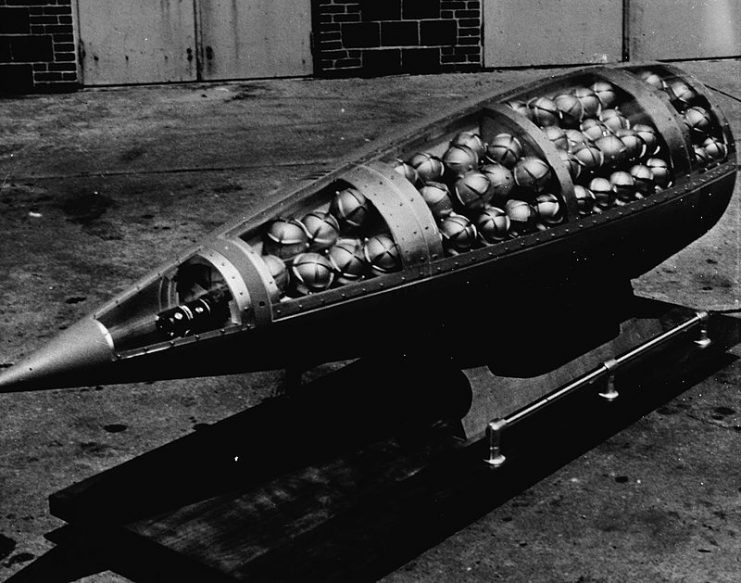

“We spent a couple weeks in the middle of the jungle,” he recalled. “The warhead we tested would come apart near the target and shoot out a bunch of smaller balls that flew in different directions and then exploded.” He added, “We had targets set up and fired two separate test rockets while we were there to measure the amount of damage they could inflict on enemy forces.”

The exercise in Panama would become his final temporary duty assignment since he returned to Ft. Bliss and finished out the remainder of his enlistment in April 1959. Despite the offer of reenlistment and travel to Turkey to teach the rocket system to Turkish soldiers, he admitted he was homesick and ready to return to Chicago.

For more than 18 years, Oppenheim was employed by the Chicago Transit Authority, and in 1976 he married his fiancée, Jan. Wishing to leave the “rat race” of Chicago life and to raise their children in a quieter environment, the couple moved to Jefferson City in the summer of 1977.

“I worked for the Department of Corrections for about 18 months and then went to work for the old Capital City Water Company, spending 22 years with them,” he said. “In 1981, I enlisted in the Missouri National Guard and became a cook until retiring from there in 1998.”

In addition to having worked part time as a cook at St. Peter Interparish School and with Jefferson City Public Schools, Oppenheim and his wife have volunteered with Operation Bugle Boy—a nonprofit organization that honors veterans, military members and first responders.

When asked about the impact of his service with the U.S. Army during a Cold War period that was sandwiched between the Korean and Vietnam Wars, the first-generation American asserts that for him it was an honor to have had the opportunity to serve the nation that was first home to his parents.

Want War History Online‘s content sent directly to your inbox? Sign up for our newsletter here!

“I just love this country and everything it represents,” Oppenheim said. “I loved being in the Army and all of the wonderful people that I came into contact with because of it.”

In mirthful reflection, he concluded, “We all came from different backgrounds and communities but learned how to work together to get the job done. To this day, I can still remember all the names of most of the people that I served with.”

Jeremy P. Ämick writes on behalf of the Silver Star Families of America.