To the people of Cuba, both on the island and outside, there is no greater champion of freedom than Jose Martí, but the names of Maceo and Gómez aren’t far behind.

Both being older than Martí, Maceo and Gomez already had a long history of struggle against Spanish colonization. Indeed, they were both already leaders in the battle for independence when the future hero was only a child.

Martí knew that, without Maceo and Gómez, he could not unite the island citizens in the final war of independence. In addition, their acceptance of his leadership was one of the cornerstones of Martí’s influence. He never forgot it and, even though there were disagreements, was extremely grateful.

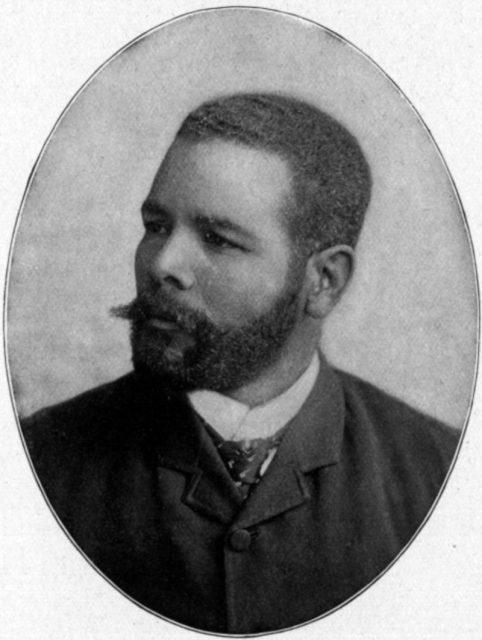

Antonio Maceo

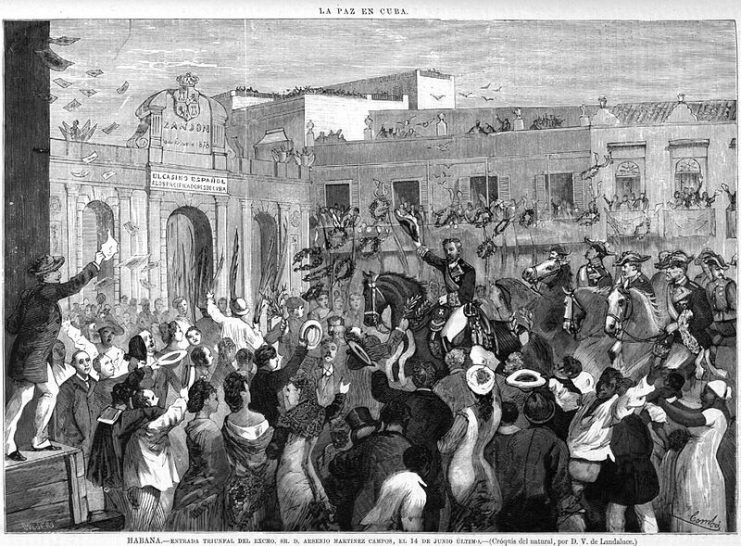

Antonio Maceo is best known for two notable events: refusing to accept the agreement offered by Spanish Governor, Arsenio Martínez, to end the Ten Year War and, almost two decades later, leading the offensive toward the western part of Cuba during the War of Independence.

Known as the “Bronze Titan” because of his skin color, courage, and military shrewdness, Antonio Maceo y Grajales was born on June 14, 1845, in San Luis, a small town near Santiago de Cuba. He was the son of a Venezuelan father and a Cuban mother.

He found success as a businessman and farmer. However, his interest in Freemasonry and the ideals of equality espoused by the organization led to political activism. Eventually, he became obsessed with Cuban independence from Spain, freedom for the slaves, and racial equality.

Once the Ten Years’ War broke out, Antonio Maceo enlisted in the revolutionary army as a private. Through his leadership skills, valor, and character, he was rapidly promoted through the ranks and became a general.

When the other leaders accepted Spanish reforms and terms to end the conflict, he refused to surrender his weapons in the famous Protesta de Baraguá (Baragua Protest), Baraguá being the venue of his meeting with Governor Martínez. Instead, he marched into exile.

Although not always agreeing with Martí, Maceo would eventually accept the younger man’s leadership for a new fight for independence. Maceo was appointed second-in-command of the insurrection. Only Gómez outranked him. Martí was the political leader.

When Martí was killed early in the War of Independence, Maceo and Máximo Gómez would assume total control of the revolution.

Maceo fought in close to 1,000 battles and skirmishes. He was wounded 26 times and lost his father and various brothers in the war. He was killed in combat in Punta Brava, near Havana, on December 7, 1895. Maceo was only 51 years old. His aide, Lieutenant Francisco Gómez Toro, son of Máximo Gómez, was also killed while protecting the body of his fallen general.

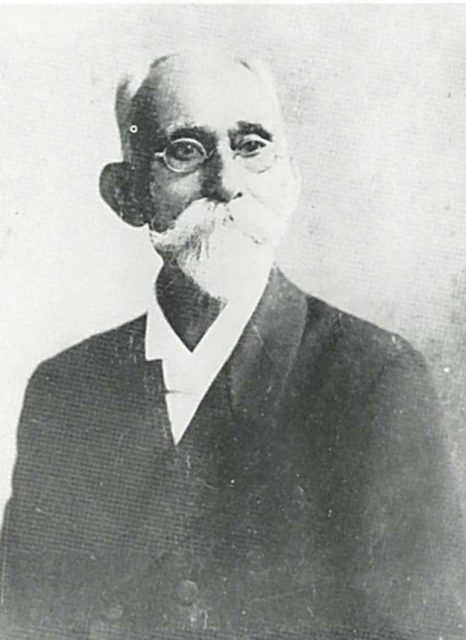

Máximo Gómez

If it had not been because he detested politics and distrusted the American occupying forces, Dominican-born Máximo Gómez Báez would have been the first president of an independent Cuba.

Gómez was born on November 18, 1836, in the small town of Baní, Peravia province, Dominican Republic.

As a young man, he was an ardent supporter of Spanish colonialism. He fought against a Haitian invasion in the 1850s and later joined the Spanish Army. He received cavalry training at the Zaragoza Military Academy in northeastern Spain.

Back in his country in 1861, he fought in the Dominican Annexation War which reestablished Spanish rule over the Dominican Republic. He fought on the side of the Spaniards and when the war ended in 1865, he settled in Cuba.

Even though he was not pleased with the way the Madrid government treated those born of Spanish parents in the New World, he accepted a commission as cavalry colonel in the colonial army.

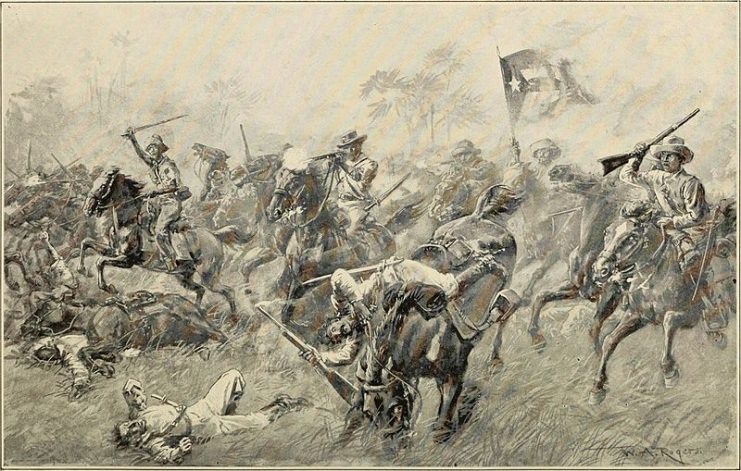

But within three years, disgusted with the ill-treatment the Cubans suffered, Gómez had changed his mind. He joined the rebel army in 1868 and was responsible for the development of the machete charge, a military manoeuvre which terrified the Spanish troops.

At the end of the Ten Years’ War, he retired to the Dominican Republic. It would not be long, however, before a young Martí approached him to fight for Cuba’s independence one more time.

Like Maceo, Gómez wanted military leadership for the rebellion. But, unlike Maceo, he was an early convert to Martí’s view that only a civilian-led rebellion which promised democracy and equality would be successful.

Due to his somewhat slanted eyes and yellowish skin, Martí affectionately, and privately, always called Gómez el Chino Viejo (the Old Chinaman).

Gómez was appointed “Generalísimo,” General of the Army, and rapidly introduced guerilla tactics. Gómez introduced a policy of scorched earth to deny the Spanish army its food supplies and to hinder the flow of goods to the authorities. He did this with great sorrow, as he had great respect for the land and its workers,

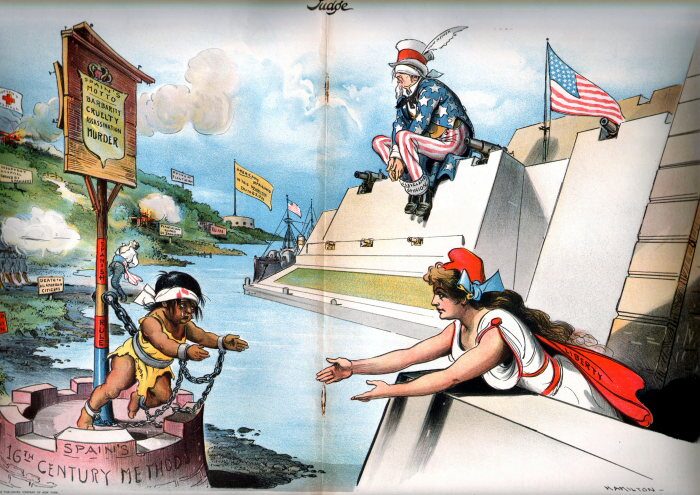

By the time the Spanish American War broke out in 1898, Gómez had the Spanish forces on the ropes. He rejected an appeal by the Spanish governor to join him in fighting the Americans, but by the same token, resented American intervention.

Read another story from us: The Cuban Confederate Colonel

He was the only one of the “Big Three” Cuban founding fathers who survived the War of Independence.

On May 20, 1902, he had the honor of raising the Cuban flag for the first time over the fortress of El Morro in Havana.

Maximo Gómez died in the Cuban capital Havana on June 17, 1905.