Usually when we think of battles that are turning points of war, we think of close contests, hard-fought by dedicated and honorable men who take it upon themselves to perform the most difficult service to their country, that are won after long struggle by the eventual winning side.

The Battle of Carillon was none of those things.

In America in 1758, the British Army was split over tactics. The old guard was still devoted to the traditional way of fighting in continental Europe, lining up and advancing toward the enemy.

The new school had learned new ways of fighting in the north American woods, and saw the effectiveness of light infantry, skirmishers, and Native auxiliaries. This new way of thinking also had a powerful ally: the new Prime minister, William Pitt.

But despite Pitt’s preferences, the old school still held sway within the army, and one of its proponents was the new Commander in Chief in North America, James Abercrombie. The British had begun the Seven Years’ War with a string of losses that had eventually caused the recall of Lord Loudoun, and General Abercrombie was expected to reverse the trend.

Abercrombie was known more as a logistics specialist than a tactical general, and Pitt sent a handpicked member of the more aggressive new school to be his second-in-command, Brigadier General George Howe. Their first task was to take a key point on the route to Montreal, a small French fort at the head of Lake Champlain.

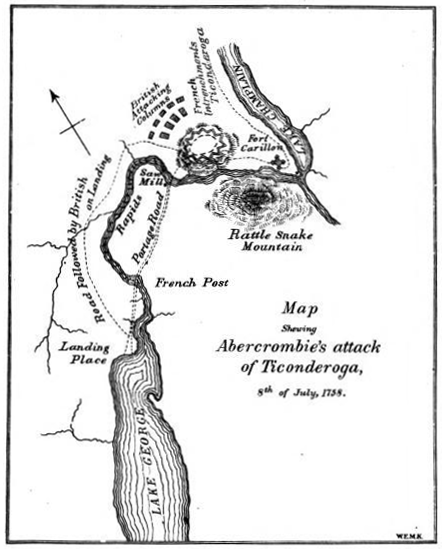

The route from New York to Montreal involved a long sail up the Hudson River, and then two portages to large lakes, Lake George and Lake Champlain.

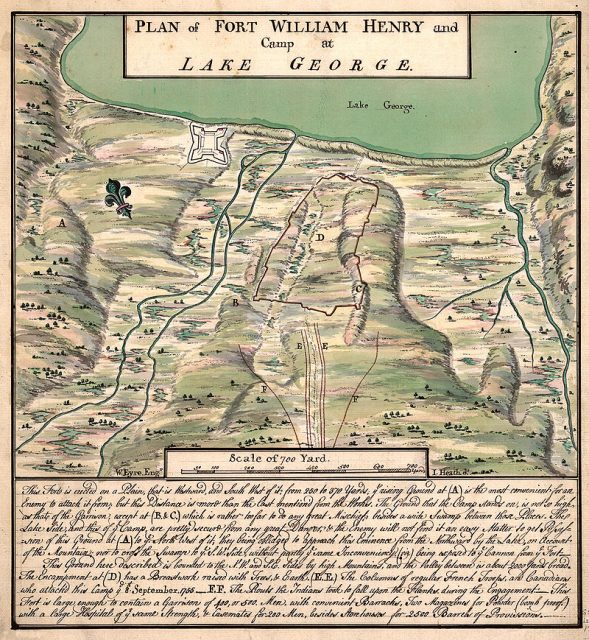

The British had held the portage between the river and Lake George with Fort William Henry until Loudoun lost it in 1757, but after his victory the French General Montcalm destroyed the fort and retreated, leaving the portage open.

The portage between the two lakes was commanded by a peninsula called Ticonderoga, and on it the French built Fort Carillon, which Montcalm held with four thousand men.

To attack Fort Carillon, the logistics specialist built the largest army yet seen in North America, 16,000 strong. They assembled at the ruins of Fort William Henry, took boats up Lake George, and disembarked unopposed less than two hours’ march from the fort.

But then disaster struck. The French advance guard had abandoned their camp at the sight of the British force, but Lord Howe, in charge of the British skirmishers, pursued them, and in the fighting was killed by a musket ball.

Without his aggressive and popular second-in-command, Abercrombie lost control of his force for the day, and was unable to push on all the way to Fort Carillon even on the next. Montcalm took advantage of his delay in constructing new fortifications.

The French used their wooded environment to their advantage, constructing a large abatis, a fortification made of toppled trees with their trunks and limbs sharpened, pulled together to provide a serious obstacle to approaching troops.

And here Abercrombie made a critical mistake: he sent a junior engineer to survey the ground of battle. That engineer didn’t recognize the threat of the abatis and reported that the fort could easily be taken by storm.

Presumably this would have been Howe’s duty had he survived, but rather than putting his own eyes on the situation, or as many as possible, Abercrombie relied on this report.

Fort Carillon was dominated by a hill on its south side, an unfortified hill the British could easily have placed artillery upon, and made the fort indefensible. But Abercrombie chose instead to make a direct infantry assault with his regular troops in the classic European line-of-battle style.

It was a disaster. While Abercrombie stayed at his headquarters a mile away taking reports, his troops made attempt after attempt to make it through the abatis against constant French fire, without success. At the end of the day, facing reports of nearly two thousand casualties, and without ever having seen the battle, General Abercrombie made the decision to retreat.

Late at night he ordered his army to march back to the landing place on Lake George, where the troops, with no solid information on why they were retreating, made a panicked dash for the boats, fleeing an imaginary enemy. By the end of the next day they were back at the ruins of Fort William Henry.

Montcalm was dumbfounded by his providential victory, but had too few troops and supplies to take the offensive. On the south end of Lake George, Abercrombie too settled into a defensive stance, in has case perhaps merely to await the consequences. By the standard of the time, they were not long in coming.

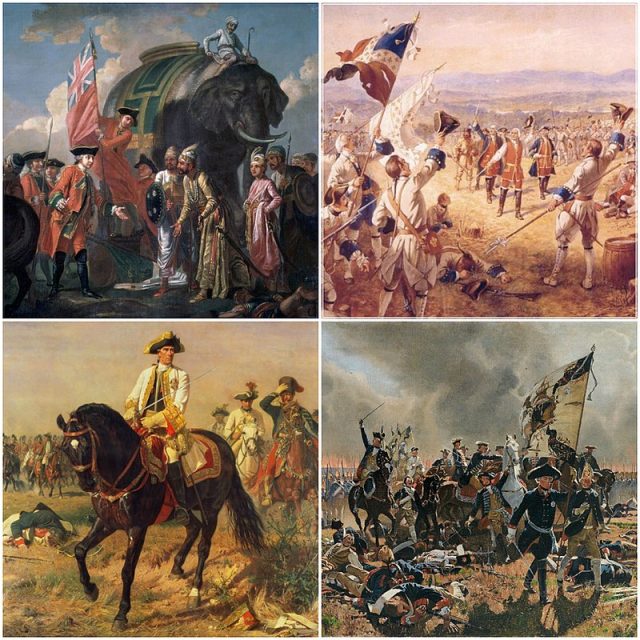

In September, Abercrombie was recalled to England and replaced as Commander-in-Chief by Jeffrey Amherst, an aggressive commander of the new school. Amherst had just shown an ability to create dramatic success by taking the French fortress at Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island at the mouth of the St. Lawrence.

In 1759 he led Abercrombie’s former army up Lake George again, and took Fort Carillon with only five killed and 31 wounded. He renamed it Fort Ticonderoga, under which name sixteen years later it would see one of the first notable battles of the Revolutionary War.

Under the capable, aggressive General Amherst, the British pursued a three-pronged attack on New France, eventually capturing both Quebec and Montreal, as well as all notable French fortifications in the west. At the end of the war the entire colony was held by the British, who preferred to use the Native-derived name of Canada.

Despite the disaster, Abercrombie was promoted on his return to England, though kept in logistical roles. Both he and Amherst held key political positions during the Revolutionary War.

Montcalm was killed in 1759 defending Quebec.