In the days of the Mexican-American war, U.S. forces marched 2000 miles, from New Mexico to California—the longest march in the history of the U.S. army. They marched under command of Colonel Stephen Watts Kearny, intending to bring California under complete U.S. control. On arrival, the second day of December 1846, they planned to launch a surprise attack. But when they came, the Californios were already waiting.

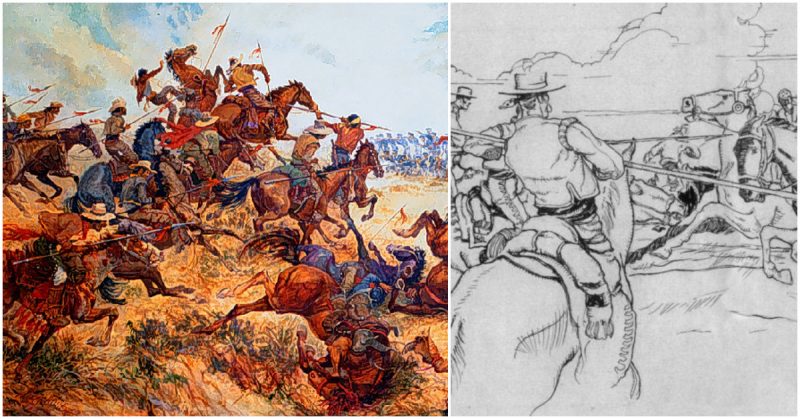

Memories of December 6-7, 1846 were etched in the soils of California, following the hostilities that rocked San Pasqual Valley in the bloodiest battles ever fought there.

California was a Mexican province in 1846. But due to Americans’ renewed vigor surrounding the west-bound Manifest Destiny movement, it would soon bid farewell to its relative peace and quiet.

Following a skirmish along the Rio Grande River in the spring of 1846, the U.S. Congress declared war on Mexico. President James K. Polk, being an ardent believer in Manifest Destiny—a philosophy that the U.S. was meant to expand across North America—ordered that all Mexican regions within what was then known as Upper California be acquired for the United States.

Col. Kearny was called upon to lead the Army to Upper California, thanks to his accomplishments with the First Dragoons at Fort Leavenworth, Missouri. Promoted to the rank of Brigadier General, he embarked on an expedition to acquire both New Mexico and California. He was assigned an initial force consisting of 300 regular soldiers, the Mormon Battalion, and 1,000 volunteers from Missouri. They were designated The Army of the West.

Without violence, New Mexico yielded to the U.S. Next stop would be California.

After the rather easy acquisition and garrisoning of New Mexico, Kearny set up a civilian government there, and after four weeks of success, he marched his Army of the West toward California. Speed was essential in this quest because President Polk wanted America to have sufficient military presence in California so as to lay claim to it after peace was declared with Mexico.

Meanwhile, a little storm was rising in California as some American settlers in California begun revolts, attacking indigent Californians in several regions in the North. The American annexation of California was a rising debate within the province. Several Californians supported the annexation, while others raged against it and launched revolts of their own in their small unorganized groups. There was also a group of Californians who paid no mind to whoever ruled them.

Adding to the rising storm in the summer of 1846, elements of the U.S Navy Pacific Fleet seized coastal settlements in the north of California.

While Kearny and his army moved through the desert country, they met the famous frontiersman Kit Carson, who told Kearny about the events going on in California. California seemed to have capitulated to Commodore Robert F. Stockton. This meant that Kearny’s Army of the West was no longer needed. Thus, he sent the bulk of his force to Santa Fe, retaining only about 100 men.

Kearny’s remaining force would proceed to California, sending word ahead that he had annexed New Mexico and was on his way to California. He also requested that escorts be sent to him.

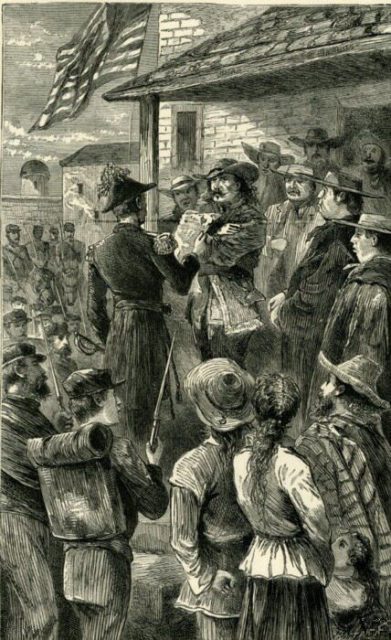

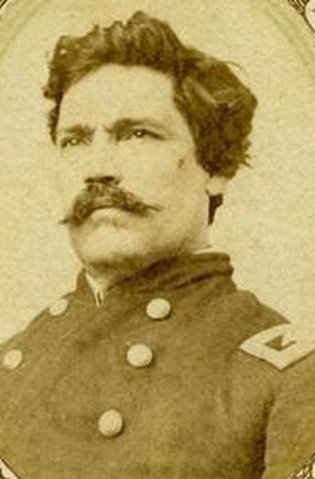

This request was promptly granted by Stockton, who sent Lieutenant Archibald Gillespie with about 37 riflemen and a field gun out to meet Kearney. Upon meeting, Gillespie told Kearny about hostile Californios led by Andrea Pico, who were less than 6 miles away in San Pasqual.

On December 2, 1846, after traveling a distance of 2,000 miles on ill-conditioned horses, Kearny’s troops were at Warner’s Ranch, California.

Knowing about the Californios’ presence in San Pasqual made Kearny and his troops thirsty for battle. They were eager to fight, after six long months of no action.

Kearny set up a war committee, planning a reconnaissance operation ahead of an attack that was to be launched the next morning. A captain named Moore disapproved of the plan, stressing the fact that although the soldiers were eager to fight, they and their horses were too worn out and not a match for the Californios.

He said that Kearny was underestimating the enemy, and that the Californios were masters of the terrain who also boasted of highly skilled horsemen. So, he suggested that Kearny launch a surprise attack on the Californios’ camp, and take them on while they were not mounted on their horses.

His suggestion was overruled.

Kearny sent Lieutenant Thomas Hammond with six dragoons, along with a deserter named Machado, to reconnoiter the enemy camp. This proved to be a costly mistake.

When the reconnaissance team, guided by Machado, came close to an Indian camp in San Pasqual Valley, Machado went into the camp to make inquiries, leaving Hammond and the dragoons behind. Machado learned that Pico and about 100 men were resting nearby, completely unaware of the U.S. presence. This was a perfect scenario for a surprise attack.

However, half a mile away, Hammond was growing increasingly impatient and possibly suspected that Machado was setting him up. So he charged into the camp with his dragoons, causing a commotion in the camp, and alerting the nearby Californios to the American Presence. They rallied around yelling “Viva California, Abajo Los Americanos.”

With the element of surprise now lost, Kearny opted for an immediate attack. He rallied his men for battle, even though they were still travel weary, and their horses were in no better condition.

Their weapons and equipment were wet and cold. What they had intact was their taste for action. So, contrary to Captain Moore’s advice, Kearny led his virtually unarmed troops against a vicious yet underrated enemy.

Early on December 6, 1846, the troops went past the ridge between Santa Maria and San Pasqual. In the meantime, Kearny ordered his troops to keep casualties at a minimum. They were to surround the Californio camp and capture fresh mounts while subduing the Californios with their sabers.

While descending the rocky path, they were engulfed by the early morning fog. Confusion began to have its way with them. This became evident when Captain Johnston suddenly yelled “charge!” at 40 of his best-mounted men, who drew their sabers and sped with him far off the main body of the force, charging towards the Californio camp over a thousand yards away.

Kearny was crestfallen: he had issued an order to Johnston, but he had not said “charge”, he had said “trot”. Apparently, his words were misinterpreted, and it cost them.

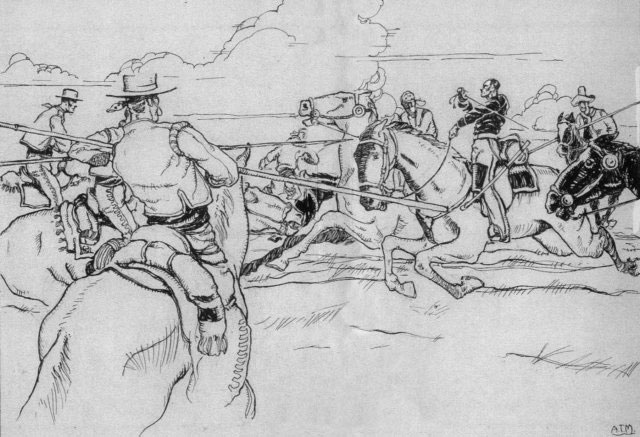

Seeing the charging troops far ahead, Pico and his forces took off and headed towards Kumeeyay village. They were armed with long lances and reatas (lariats), which they used effectively against the U.S forces, whose weapons which had been reduced by wetness to sabers and rifle butts.

At Kumeeyay, the Californios fired their few firearms. Captain Johnston got hit by a bullet and he died on the spot.

Captain Moore’s force continued to give chase. The Californios were masters of the San Pasqual terrain, so they kept eluding the U.S. forces. When they got to higher ground, they counter-attacked, charging at Moore’s force with their long lances. During the fight, Moore was killed, having been stabbed several times with lances.

By the time Kearny caught up with the action, chaos already reigned. Every man was on his own. Kearny’s orders were no longer relevant. He eventually was wounded by a stabbing thrust in the back.

Gillespie and his men got special attention from the Californios, who hated him for his actions in Los Angeles. He received a lance thrust just over his heart. But he successfully fought off the vicious attack with his saber, until he joined the artillery pieces which had just arrived.

He brought a howitzer into action with the help of James Duncan, a naval midshipman. A blast from the howitzer caused the Californios to scatter down the valley, abandoning the battlefield to the Americans, who then fortified a camp on a hill north of the valley.

Having fought under very dreadful conditions, with poor mounts and damp weapons which refused to work, the U.S forces were said to have fought with bravery against towering odds.

50 Americans were directly engaged in the battle, and of these, 17 were dead and 13 injured. Six officers died, including Captain Johnston, Captain Moore, Lieutenant Hammond, two sergeants, and one corporal. General Kearny and Captains Gillespie, Warner and Gibson were seriously injured.

The battle of San Pasqual is among the very few military battles in the U.S. that involved the participation of elements from the Army, Navy, Marines, and civilian volunteers, all in one skirmish.

Read another story from us: Between Two Rivers: Opening Shots of the Mexican-American War

Having eventually succeeded at getting the Californios to retreat from the valley, the U.S. forces, according to some historians, were said to have earned the victory, albeit a pyrrhic victory. This opinion is countered by other historians who believe that the Californios equally deserve to be counted as victorious, owing to their sheer bravery and masterful actions in the battle of San Pasqual.