The Opium Wars extended the might of the British Empire to the remote Chinese Empire, expanding its trade and national prestige. In exchange, China would find itself weakened by internal strife, its population ravaged by drug addiction.

It would not be long before a more modern, more aggressive Asian nation took advantage of China’s weakness to supplant the former Pacific power. Though the Second Opium War was a war of national pride, the First Opium War was a war for commerce.

The war started over increasing tensions regarding the opium trade, and it was the future British port of Hong Kong that would see those tensions boil over into open conflict. The catalyst was when the Chinese High Commissioner, appointed by the Emperor to curtail the opium trade, made the fateful decision to arrest a foreigner. Specifically, he arrested and detained an officer of the British ship Carnatic.

It did not take long for the officer’s crew to retaliate. On July 12, 1839, thirty British seamen went ashore at the village of Jianshazui, located on the Kowloon peninsula north of Hong Kong. Like any good riot, the sailors began by apprehending and consuming a large quantity of alcohol. Appropriating a substantial store of local rice wine, the party proceeded to riot, vandalizing the town and assaulting any locals who got in their way.

As a result of the rioter’s antics, one local died from their wounds. Both the British Superintendent of Trade and the High Commissioner blew a metaphorical gasket at the news; Superintendent Charles Elliot attempted to stall until reinforcements arrived from India. His opposite, High Commissioner Lin Zexu’s, ire needed no explanation.

Elliot attempted to bribe the problem away, but Lin was above such antics. In accordance with Chinese law, Lin demanded the persons responsible for the local’s death be presented for execution for murder.

Elliot refused to hand over the culprits, instead ordering an inquiry for five of the sailors for rioting and assault. As a show of good faith to the High Commissioner, Lin was invited to send officials to observe the proceedings.

Even more incensed at British presumptuousness, Lin refused the invitation and ordered an embargo –any local selling food or water to the foreigners would be executed. In response, the British evacuated the peninsula, taking shelter on ships offshore in the harbor.

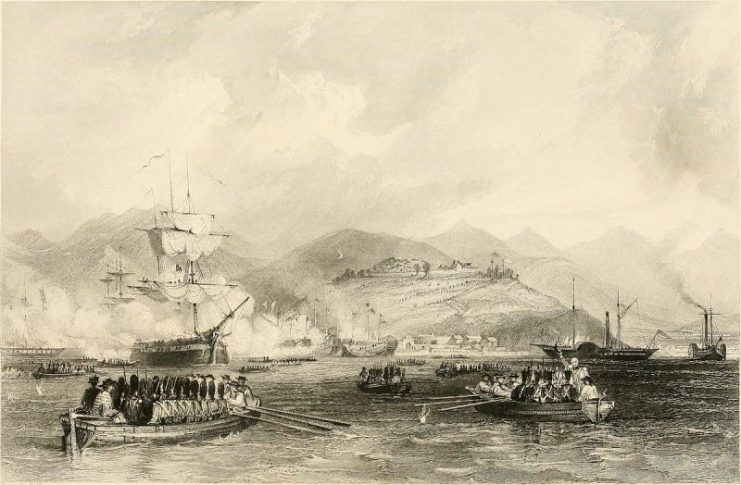

Chinese war junks entered the harbor, and by August 25th the British completed their evacuation. Elliot, meanwhile, anxiously awaited reinforcements to protect his fellow subjects and put the Chinese in their place.

Three days after the last Britisher left the island, three frigates of the Royal Navy arrived. Tensions mounted as both sides saber rattled to attempt to impress their opposite. Both sides, blinded by xenophobia and, in the British case, legitimate weaponry, remained unimpressed.

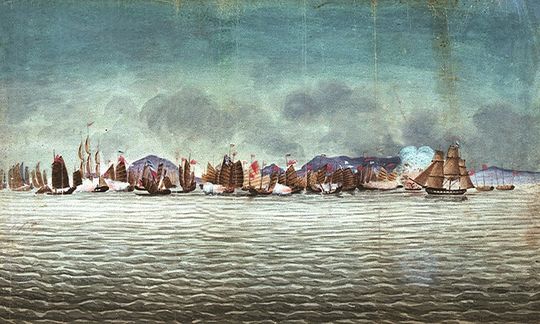

After a last stab at diplomacy failed, Elliot ordered several ships to attack the Chinese vessels suspected of poisoning local wells. Elliot gave the Chinese until 2:00 pm to resume provisioning of the British residents. The Chinese did not respond, and, diplomacy exhausted, a British vessel opened fire on the Chinese junks. The first shots of the First Opium War had been fired.

An eyewitness account of the first battle of the war reported that “the Junks then triced up their boarding nettings, and came into action with us at half pistol shot; our guns were well served with Grape and round-shot;… they opened a tremendous and well directed fire upon us, from all their Guns… the Junk’s fire Thank God! Was not enough depressed, or if otherwise, none would have lived to tell the Story.”

Having over-aimed their guns, the Chinese cannon failed to quell the British forces. Despite this, according to the account, “the battery opened fire upon the English at 3:45 pm, and their fire was steady and well-directed…at 4.30, having fired 104 rounds, the cutter had to haul off as she was out of cartridges. The junks immediately made sail for the Louisa… We… gave them three such Broadsides that it made every rope in the vessel grin again. We loaded with Grape the fourth time, and gave them Gun for Gun….”

Despite inferior Chinese gunnery, the British failed to subdue the Chinese. Elliot began to worry if his forces were insufficient. The Chinese, meanwhile, emboldened by what they quickly rewrote into a resounding victory against the foreigners, prepared their defenses against an expected invasion.

As the two sides readied for war, Lin, having written of sinking a two-masted warship and inflicting fifty British casualties when the Chinese sunk nothing and killed no one, believed the Qing Dynasty stood a chance against a modern Western power.

Their confidence would be short-lived, as would British trepidation. Despite a lackluster start, the First Opium War would herald a new era in British-Chinese relations that would leave a sour taste in both Empire’s mouths.