The Duke of Marlborough was one of the greatest military commanders in British history. His stunning success at the Battle of Ramillies on 23 May 1706 was one of the battles which made his reputation, and which proved the decisive effect a single clever manoeuvre could have in the right hands.

The Man and the War

John Churchill, the First Duke of Marlborough, earned his noble title by being the leading British general of the late 17th and early 18th century. An ambitious and effective commander, he rose to the position of general through a combination of skill and patronage, before leading the British to a string of successes in the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-14).

This war was the first that could be considered global. A network of alliances drew the nation states of Europe into a continent-wide conflict using professional armies and then exported the war around the globe via colonial holdings. As the powers grappled to decide who would inherit Spain, Marlborough became the leading light of the Grand Alliance.

Equally Matched Armies

In 1706, Marlborough was in the Netherlands with an army of British, Dutch and Danish troops. His initial plan to march from there to Italy was thwarted by an offensive into Germany by the opposing French, and so he found himself stuck in the Netherlands, trying to lure the French out to fight.

Fortunately for the Alliance, King Louis XIV of France was determined to gain vengeance for earlier defeats and pushed Marshal Villeroi into advancing to face Marlborough.

Both armies consisted of around 60,000 men, and both were familiar with the landscape in which they were fighting. And so, when a British reconnaissance force headed for the village of Ramillies before dawn on 23 May, they found Villeroi’s army already occupying this prime camping spot.

Gathering his army into four columns, Marlborough marched on Ramillies and battle commenced.

Left and Right Flanks

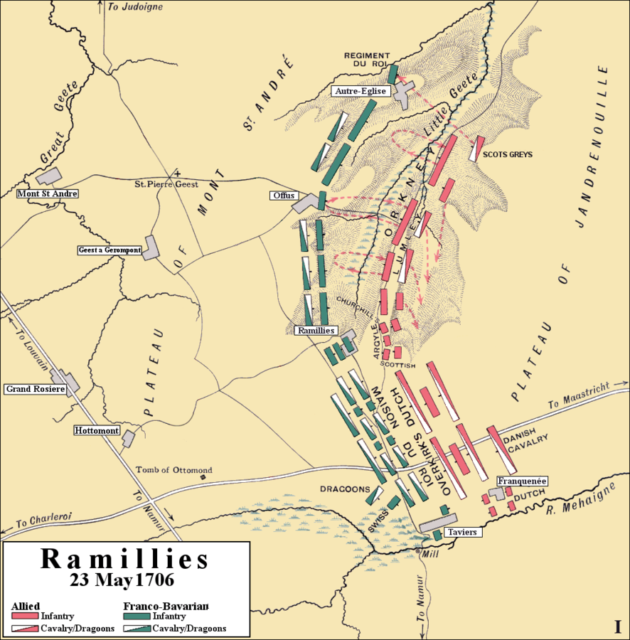

Villeroi assembled his forces in a concave formation, with the right and left flanks further forward than the centre. Both French flanks used rivers and marshes to their advantage, preventing the Allies from outflanking them.

Just after 1pm, Marlborough began the attack. He advanced his troops strongly toward both the left and right flanks of his enemy. He pushed the French back on the left but made less progress on the right, where his forces had to advance across marshy ground. Still, this advance on the right was strong enough for Villeroi to divert troops there from the centre.

A Strong Centre

Villeroi’s position in the centre appeared strong. His troops were lined up along a ridge. Their concave formation meant that any Allied advance in the centre would be bombarded with fire from multiple directions and risk being surrounded.

But this hid two weaknesses which would prove fatal in combination.

Firstly, the French were thinly spread to cover their extended position along the ridge and both flanks.

Secondly, they could not easily move troops from one flank to the other, as this would involve manoeuvring them around the outside of the army’s curve.

As a result, the French line was weak in many places, and could not easily be reinforced if it began to collapse. The Allies, on the other hand, could easily move troops from one flank to the other of their convex formation. Theirs was the strong centre.

Thousands of Men Sneaking

From the middle of the afternoon, fierce fighting developing on the Marlborough’s left. French cavalry was committed there and was gaining an advantage. Marlborough was able to divert troops from his opposite flank, and together with Danish troops on the left they enveloped and defeated the French cavalry.

The French flank was pushed back at a right angle to the rest of the army.

Now came Marlborough’s master stroke. Many of his troops on the right were hidden from French view behind a ridge. Leaving their banners in place to create the illusion that they were still there, he marched half these troops across the back of his own army, hidden from enemy view. Thousands of men snuck from the right to the centre, where they faced Ramillies itself, the hinge point of the folded French line.

Taking Ramillies

Marlborough began a devastating bombardment against the defenses of Ramillies, followed by an advance by his superior numbers in the center. Villeroi could not divert troops to defend the position – his right flank had collapsed while his left was still holding off the imagined threat from the banners of the British right.

The fighting for Ramillies was fierce. Marlborough committed his men to the risk of a full-on assault. The risk paid off. By 7pm, the Allies were storming Ramillies, and Villeroi himself came close to being captured as his army was swept away.

The Failed Second Line

Villeroi made one last attempt to halt Marlborough, forming a second line behind his original positions. But the French army had been shattered, its morale and formations left in ruins. Allied cavalry swept away this attempt at a last stand, pursuing the French into the night.

By dawn on 24 May, Villeroi had lost a huge portion of his army, leaving the field in Allied hands. He left behind 13,000 casualties and 6,000 men taken captive. The Allies, by contrast, lost just over 1,000 men dead and 2,600 wounded. Marlborough’s army was still intact.

Onward into the Low Countries

Ramillies was a huge strategic as well as a tactical success. With Marlborough now largely unopposed, the Spanish Netherlands lay open to him. Ath, Louvain, Brussels, Antwerp, Ghent, Bruges, Ostend and Menin all surrendered to the Allies. These wealthy lands on the French border now lay in Allied hands.