The Japanese battleship Musashi–named in honor of the ancient Japanese province of Musashi, today the Tokyo Metropolis–was the second battleship of the Yamato-class, and was the last warship built for the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) at the Mitsubishi Heavy shipyard in Nagasaki.

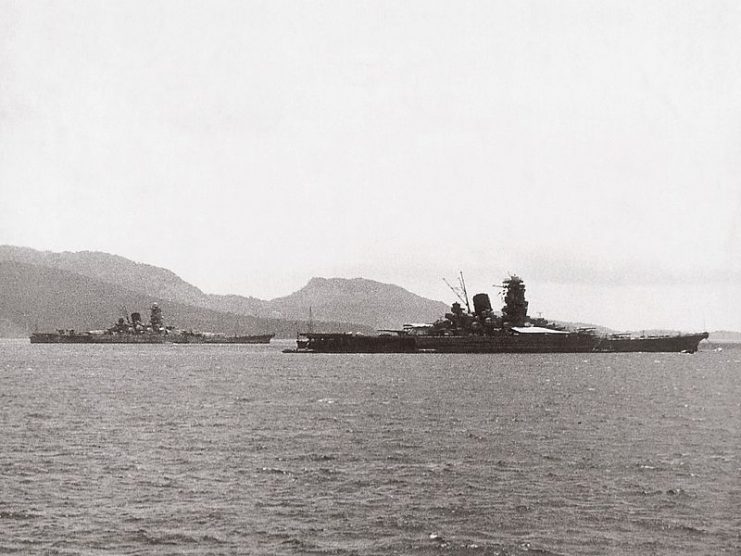

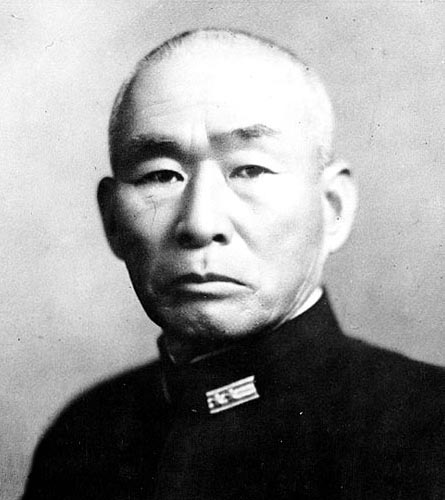

Construction commenced on March 29, 1938 and was completed on August 5, 1942, when Musashi was put in service with Arima Kaoru as captain. That same day she joined her twin, Yamato, along with Nagato and Mutsu in the 1st Division of Battleships.

The Imperial Hope

Like Yamato, Musashi was designed to fight against several ships simultaneously. The IJN’s intention was to create a fleet of “impregnable and unsinkable castles” in the sea to counter the almost infinite production capacity of the United States Navy (USN).

Musashi was constructed completely in secret, and the facilities where it was assembled were camouflaged. At the time of her launch, a mock air attack was carried out against the city to keep all the people inside their homes.

The United States government never discovered Musashi while it was being constructed.

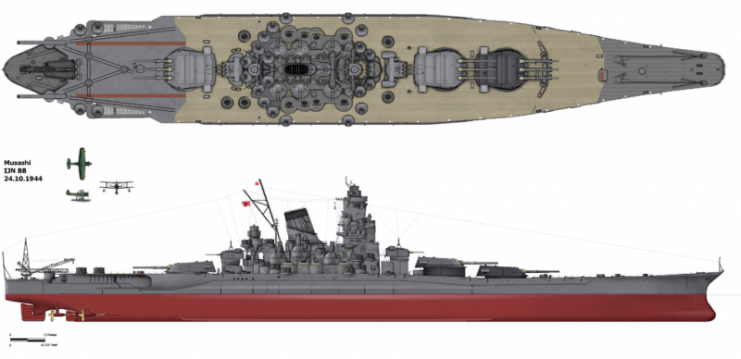

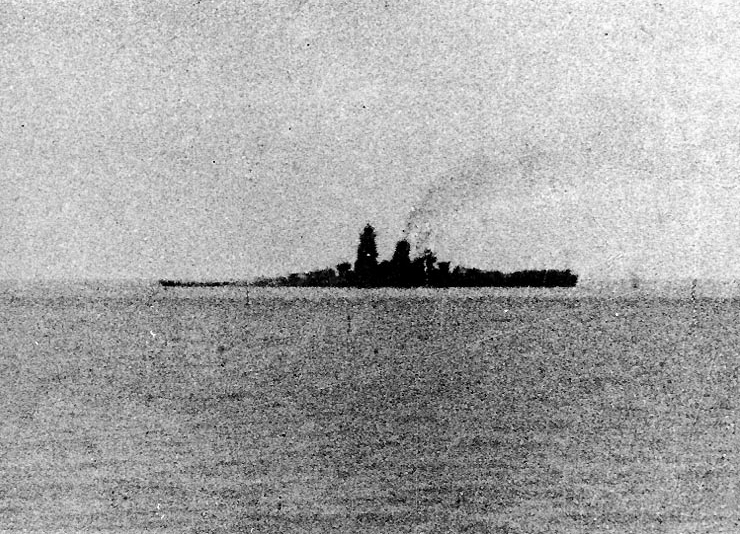

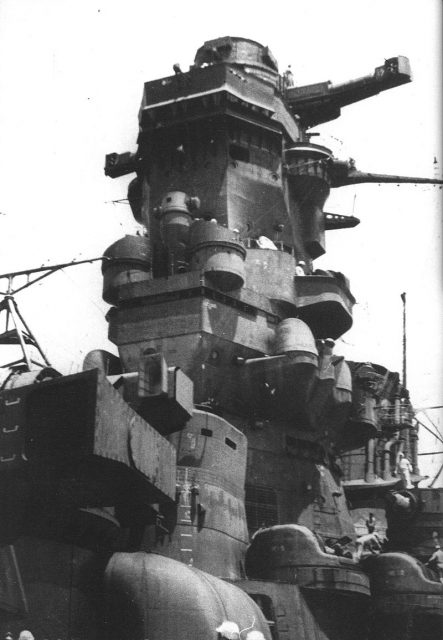

The battleship was equipped with nine 460mm guns, the highest firepower ever available on a warship. Its length was 862 feet, about 260 meters, and it weighed 71,659 tons. Its maximum speed was 28 knots. Musashi could transport 2,399 sailors.

Musashi was remodeled in 1944. The configuration of the secondary battery changed to six 155mm guns, twenty-four 127mm guns, and 130 25mm anti-aircraft guns.

Never Faced Another Battleship

The military history of Musashi is practically non-existent. She reached full operational status in January 1943 after leaving Kure to join her division at the Japanese naval base located in Truk, but Musashi then spent her short life transporting troops and supplies, or discharging her antiaircraft artillery against Truk, an atoll of the Caroline Islands.

On May 17, in response to U.S. attacks on Attu Island, Musashi was deployed in the North Pacific along with two light aircraft carriers, nine destroyers and two cruisers. However, the island fell before the Japanese force could intervene, so the counterattack was canceled and Musashi returned to Japan.

On September 18, 1943, Musashi left Truk accompanied by three other battleships to respond to U.S. incursions into the Eniwetok and Brown Islands, part of the Marshall Islands. Seven days later the fleet returned to Truk without having contacted enemy units.

In October, as a result of suspecting a U.S. attack on Wake Island, Musashi led a large fleet under the command of Admiral Mineichi Koga, formed by three aircraft carriers, six battleships, and eleven cruisers that attempted to intercept American aircraft carriers. As there was no contact, the fleet returned to Truk on October 26, where Musashi remained until the New Year.

On March 29, 1944, Musashi sailed from the island of Palau. Almost immediately after departure, Musashi and her escorts were attacked by the American submarine USS Tunny, which fired six torpedoes against the battleship. One torpedo struck near Musashi‘s bow, causing a flood.

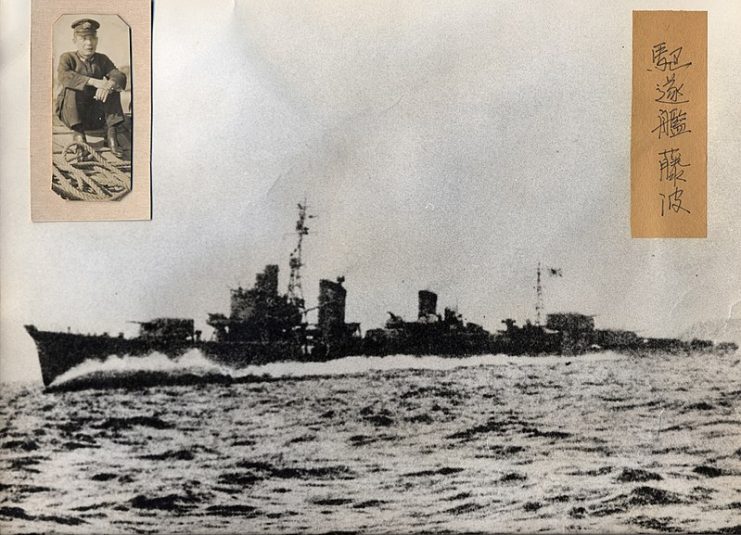

At nightfall, Musashi left to Kure to be repaired, escorted by the destroyers Michishio, Shiratsuyu and Fujinami. Despite its thick armor, Musashi had proven to have weaknesses near the prow.

Battle of the Philippine Sea

On June 19, 1944, Musashi was assigned to Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita’s 2nd Fleet in the Battle of the Philippine Sea, in which Musashi did not play a significant role due to not making contact with the U.S. fleet. This battle marked the fate of the Imperial fleet.

The Americans called the battle the “Great Marianas Turkey Shoot” because of the immense losses suffered by the IJN. The naval aviation arm of the IJN ceased to be an “oceanic” force–after that, their remaining aircraft would take off mostly from mainland air bases, resulting in a very short range to protect the fleet at sea. Soon, Musashi would fall prey to this new scenario in the war.

The Americans, now with air bases closer to the Philippine Islands as well as air superiority, continuously harassed the Japanese air bases in the Philippines. This had decisive consequences toward the achievement of American air superiority during the great Battle of Leyte Gulf four months later.

Operation SHO-GO (Victory) – The Battle of Leyte Gulf

The Japanese high command designed Operation “SHO-GO” as a counterattack to the U.S. landing on the island of Leyte. The Japanese plan involved the sacrifice of an aircraft carrier decoy fleet, commanded by Jisaburō Ozawa, to attract the U.S. Third Fleet away from the San Bernardino Strait, while the main Japanese fleet would attack at Leyte Gulf.

There, the plan proposed, the Central Force of Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita would penetrate Leyte and destroy the forces that had been landed by the enemy. With this objective, five battleships, among which was Musashi, and ten heavy cruisers departed Brunei in the direction of the Philippines on October 20, 1944.

The Japanese fleet was divided into three squads that would attack from different directions. From Borneo would come Force A, commanded by Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita; from Nagasaki Force B would attack, under Vice Admiral Kiyohide Shimay; and finally, from Singapore, Force C would sail under Vice Admiral Shoji Nishimura.

The separate Ozawa decoy fleet, meanwhile, was designed to be sunk by the enemy–it was composed of the last 4 aircraft carriers that were left to Japan, which had few aircraft to fill them. Some training ships, 2 old battleships, 4 cruisers and 8 destroyers were also part of the decoy fleet.

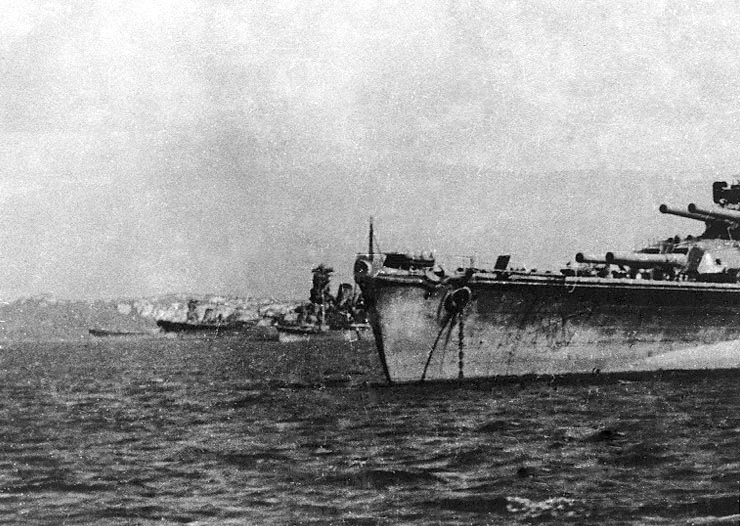

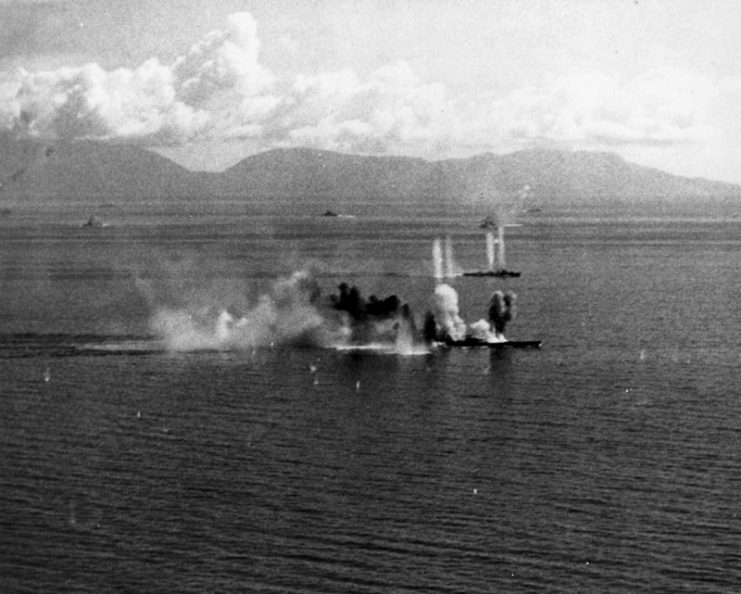

On the morning of October 24, 1944, while navigating the Sibuyan Sea to pursue the SHO-GO mission, Musashi lookouts reported the sighting of three PB4Y type reconnaissance aircraft. The air alarm was sounded. An aerial attack on the fleet was imminent, and so it happened that Kurita’s Central Force fell under a major U.S. air strike.

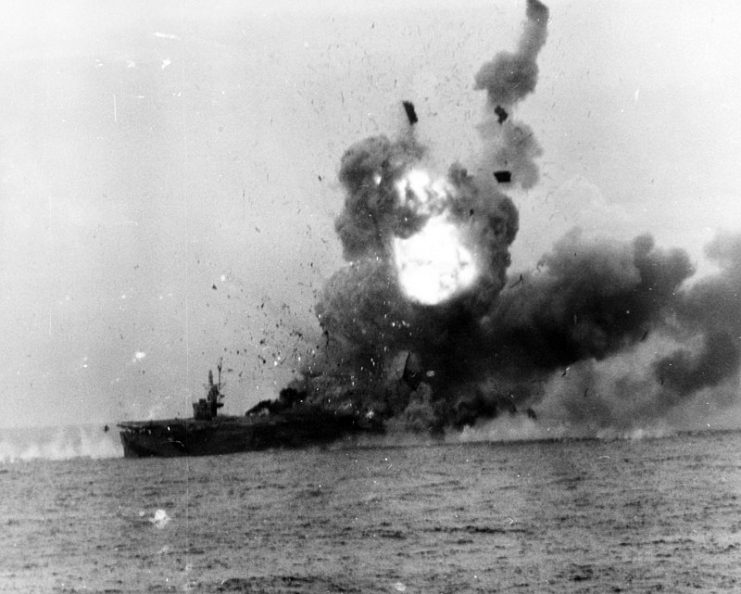

Musashi was attacked by approximately 259 aircraft launched in 6 waves from the aircraft carriers USS Intrepid, USS Essex, USS Franklin and USS Enterprise. The attacking aircraft were Curtiss SB2C “Helldiver” bombers and Grumman TBF “Avenger” torpedo bombers.

Musashi received a total of 19 torpedo hits, 10 to its port and 9 to its starboard side, 17 bomb impacts, as well as suffering from 18 near-misses on the water near its hull. After a punishment of that magnitude, Musashi was lagging behind the other ships of the fleet, leaving a trail of fuel, steaming and sunken at the bow, but still moving with three propellers.

Agony of a Giant

With the fate of Musashi sealed, Admiral Inoguchi tried to beach her on a nearby island, but the engines stopped before he could get her there. Admiral Inoguchi retired to his chamber and was never seen again. Just after 7:30 PM, Musashi sank into the Sibuyan Sea. The destroyers Kiyoshimo, Isokaze and Hamakaze rescued 1,376 survivors of the 2,399 men who composed her crew.

Musashi and the rest of the ships, especially Ozawa’s fleet of aircraft carriers, that were sunk in the battle at Leyte, were sacrificed completely in vain–Japan would not recover.

The IJN was willing to sacrifice its entire naval fleet to prevent the conquest of the Philippine Islands by the Americans. However, the Japanese Empire could not change the fate of the war, and its remaining ships were anchored in safe harbors until a new suicide attack in 1945.

A Bitter End for the Yamato Class

The battleships of the Yamato class were sunk without being able to demonstrate their amazing potential. These ships were already condemned from the day of their launching. The new kings of naval battles were the aircraft carriers.

Yamato-class ships were built to face other battleships, and without a doubt they could have resisted a naval battle very well against five or six enemy battleships, sinking them thanks to their great armor and impressive main guns. But Musashi never used its guns in combat against other ships.

Musashi and Yamato were practically castles in the sea, but like the feared Tiger tank of Germany, they were easy prey for American aviators.