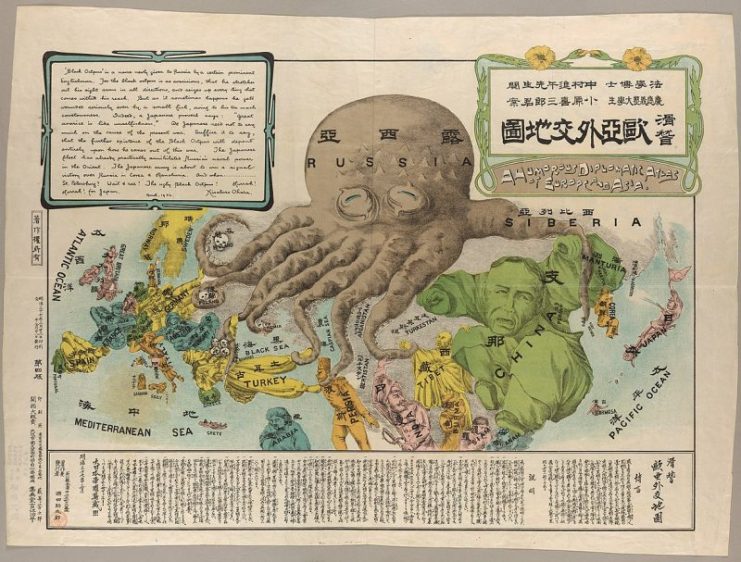

In the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905, the burgeoning Empire of Japan went to war against the massive Russian Empire. Endeavoring to expand its influence in the Pacific Ocean, Manchuria, and potentially Korea, the two nations, at odds since the Edo Period over island rights in the north, the small island nation of Japan went to war against the Euro-Asian colossus. The war would surprise many across the world, with ramifications that would stretch from the Sea of Japan to the Balkans.

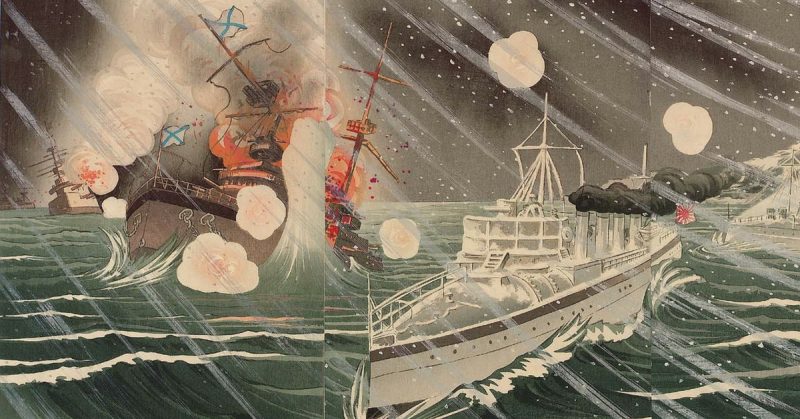

As Russia held few possessions in the Pacific, a major component of the war incorporated naval maneuvering. Russia’s Pacific fleet almost immediately found itself bottled up in Port Arthur, unable to leave to harass Japanese troop movements in Manchuria.

In desperation, another fleet was called to aid the Pacific Fleet. By treaty, the Black Sea Fleet could not sail past Constantinople, so the Russians ordered the Baltic Fleet, renamed the Second Pacific Squadron, to sail halfway across the world, bolster the Russian naval presence, break out the actual Pacific fleet, and save Port Arthur.

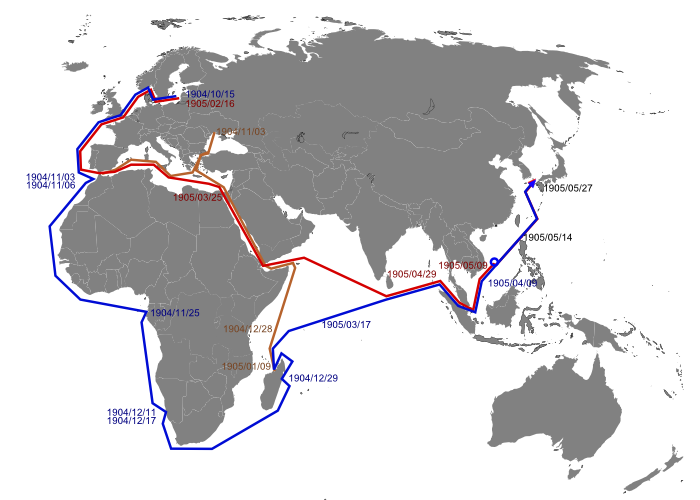

Admiral Zinovi Petrovich Rozhdestvenski undertook the monumental task of steaming an early twentieth-century fleet –and one badly in need of updating at that- past four continents, into hostile waters, and into battle, as the British refused access to the Suez Canal.

In total, the Squadron faced a journey of over 18,000 miles. Compounding matters, the Squadron faced scant chance of refueling, as international law forbade the harboring of a fleet at war. If the Admiral was going to re-supply and re-coal his vessels, he needed to think outside the box to do it.

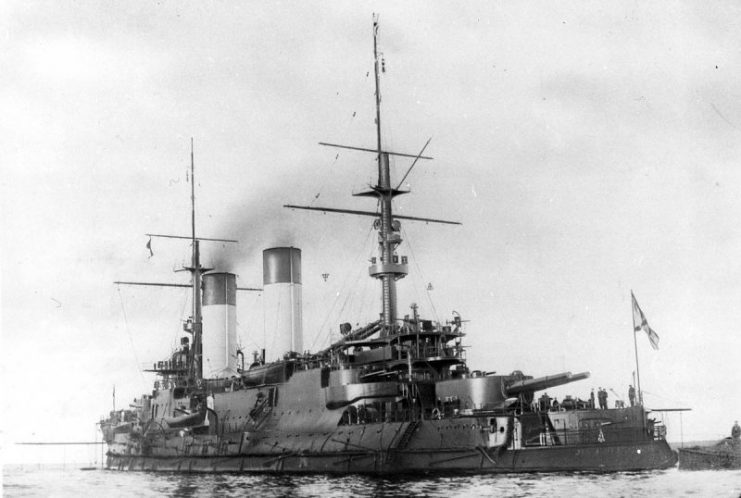

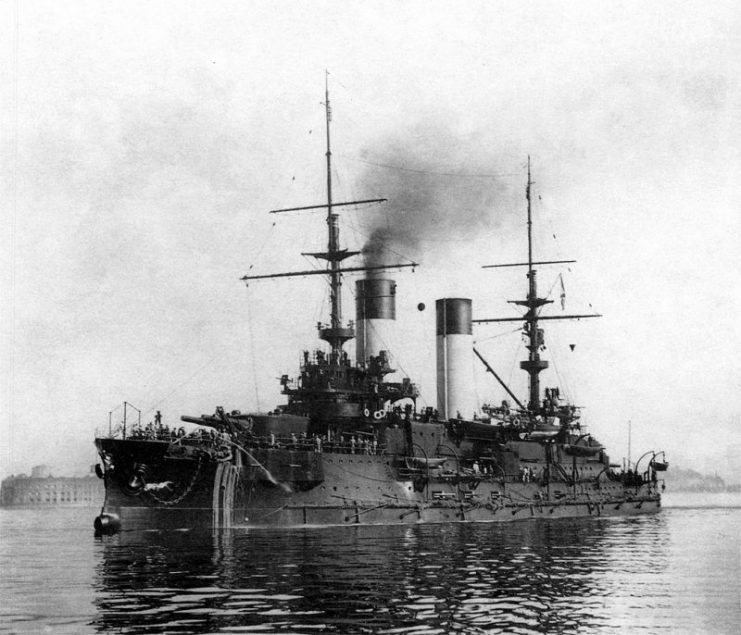

The Squadron was comprised of a hodge-podge of the modern and archaic. The Admiral’s flagship was a modern battleship, Kniaz Suvarov. Three overloaded battleships, Orel, Alexander III, and Borodino, formed the First Battleship Division of the Squadron.

Three older, less heavily armed battleships composed the Second Battleship Division, and seven cruisers, including an aging frigate rigged for sail, were also part of the Squadron, some as part of the First Cruiser Division under Rear Admiral Enquist. Nine destroyers and a smattering of support ships completed the fleet, for a total of forty-two vessels. Of course, the number of ships remained moot if they could not get to Japan.

Thanks to German aide, the Squadron successfully reached the Pacific. However, the journey was a harrowing one, including lagging, outdated ships bogged down with barnacles and seaweed, and, perhaps worst of all, insufficient ammunition for target practice along the way. Along with all the previous problems, the Admiral also nearly started a war with Great Britain.

The seemingly formidable fleet, lacking engineers, ammunition, and modern naval tactics, heaved-to toward Japan on October 11, 1904. As they sailed through the Baltic, a mantra reeking of paranoia seeped through officer’s orders, stating, “We shall all sleep in our clothes and all guns will be loaded. We shall pass through a narrow strait. We are afraid of striking on Japanese mines in these waters.”

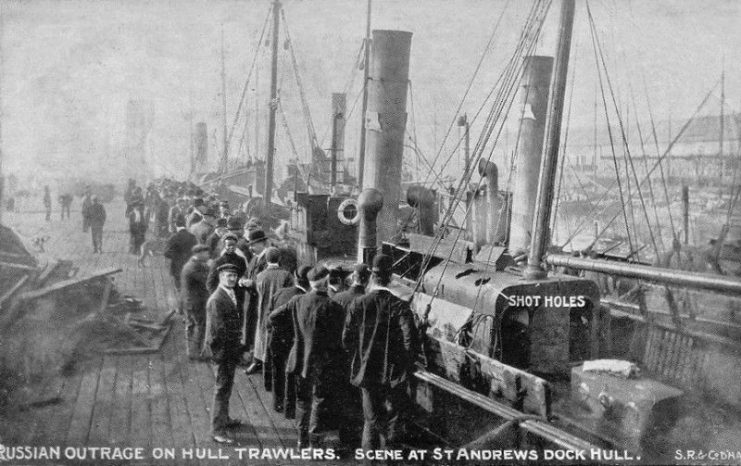

Thanks to well paid spies across the coasts and the devastating strikes of torpedo boats in the Pacific, the Russian Navy feared Japanese mines and torpedoes even within the waters of northern Europe. On the night of October 22, bugles sounded throughout the fleet as someone sighted the fishing trawler, Crane.

Terrified of Japanese torpedo boats, the Russians opened fire, killing two of the crew and wounding almost everyone else aboard. As other fishing vessels came into view, the Russians proceeded to spend twenty minutes firing on the defenseless civilians, until finally order was restored.

The vessels belonged to a British company, and the Empire’s vocal response led many to believe the might of Britannia would go to war over the incident. As the Russians coaled near the cliffs of Dover, they continued to believe they had fended off a Japanese attack, even as the best of the Royal Navy readied to punish the Czar’s forces for the affront to their dignity as rulers of the waves. As the Russian fleet continued its journey, passions cooled, and war avoided.

Coaling in Spain proved problematic at first, as the Spanish initially refused to allow the Russians to take advantage of German coalers from the America-Hamburg line in harbor. Citing international treaties on supplying warships, it was at this point that the Admiral learned of the Dogger Bank Incident, as his assault on “Japanese torpedo boats” came to be known.

Once he’d learned the truth of the incident, Admiral Rozhdestvenski appealed to the Spanish port’s commandant and officially apologized for the incident. With cooler heads prevailing, the fleet managed to coal and avoid war with the Czar’s cousin.

At a laborious pace of 9 knots, the Russian fleet steamed on to Tangier on November 1, a British cruiser squadron sticking close to observe their efforts. On November 3 the British withdrew, and the Russians, aware that the eyes of the world were upon them, sailed onward.

Admiral Rozhdestvenski was aware of those eyes, for his fleet would be one of the first to engage in a modern naval battle, battleships against battleships in the first naval warfare of the new century. All he had to do was get his various floating buckets across the world and into battle against the most rapidly modernizing Asian nation.

Concerned the older vessels in his fleet could not make the extensive journey, Admiral Rozhdestvenski split his fleet, transferred his flag, and continued sailing, re-coaling wherever he could, with several support ships joining the lumbering fleet in Madagascar. At the port of Dakar, the fleet started the arduous task of re-coaling in tropical temperatures.

A French Admiral insisted Admiral Rozhdestvenski cease coaling, but the Russian Admiral, his mood not helped by temperatures in excess of a hundred degrees Fahrenheit and humidity hovering near 100 percent, insisted that coaling resume. Shouting at the French Admiral, he declared “I intend to take on coal unless your shore batteries prevent me.”

As the city lacked shore batteries to fire with, the French backed down, allowing the Russians to load their coal in peace. Over the course of 29 hours, the sailors worked in grueling conditions, making sure to overload on coal while they still had the chance, as the next ports along the way were unlikely to provide the fleet with much-needed supplies.

Along the way, Admiral Rozhdestvenski prepared a training voyage at Gabon. Unfortunately, the fleet overshot the port, in a foreboding foreshadowing of the battle awaiting the fleet in the Pacific. Along with training, the fleet once again took on coal, staying in international waters to avoid any diplomatic faux-pas.

Through sensitive geopolitical landscapes, tropical storms, and miles upon miles of endless ocean, the Pacific Squadron chugged towards their destiny. By December 17 the fleet left the west coast of Africa, sailing towards southern Asia.

Shortly after celebrating Christmas by the old calendar, on January 7, Admiral Rozhdestvenski received the devastating news of the fall of Port Arthur. Sent to relieve the port and open up the Pacific Squadron for combat operations, the old Baltic Fleet would now serve as the primary naval force in the Pacific.

In a desperate bid to reinforce him, the Russian naval command ordered the formation of a Third Pacific Squadron. With the Black Sea Fleet trapped by international treaty, the Russians formed a third squadron from the ships rejected by Admiral Rozhdestvenski for the long voyage. The dispirited Admiral now had no choice but to wait for the vessels he’d already turned away from the taxing voyage.

As the fleets moved forward in February, Admiral Rozhdestvenski faced a threat within his own fleet: revolutionaries were inciting discontent, and the Admiral quickly quelled the intrepid insurrection, rounding up the ringleaders and arranging a vessel loaded with the sick and the increasing number of rabble-rousers back to Russia.

With discontent wracking the fleet, and paranoia of Japanese torpedo boats increasing by the day, tensions remained high on the lumbering relief force turned main battle fleet. On March 15 he received word that the Third Pacific Squadron, which he often referred to as “self sinkers” was coaling in Crete.

Unwilling to wait for the supposed reinforcements, Admiral Rozhdestvenski continued to sail for the Pacific, word of Russian defeats reaching him as he struggled to coax his ragtag force to the battlefield.

On April 8 the Second Pacific Squadron arrived off the coast of Singapore. Having sailed nearly five thousand miles and taken on coal five times in international waters, the Russian fleet’s skill at speed coaling reached record-breaking levels.

If nothing else, the voyage demonstrated an impressive logistical feat, one noted by foreign correspondents waiting for the squadron’s arrival in Singapore. Once the fleet took refuge in safe waters, Admiral Rozhdestvenski reluctantly awaited the Third Squadron, which arrived May 9. On May 14, with fifty-two ships all told, the combined Second and Third Squadrons steamed on to face the Japanese.