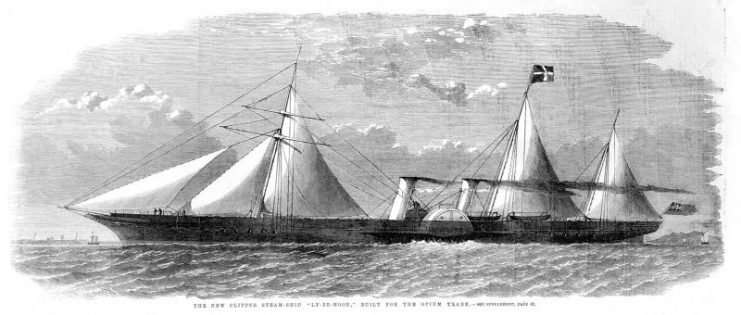

Following the First Opium War, the British Empire and Qing Dynasty of China entered an uneasy peace. Commerce continued, including the controversial opium trade, and with Hong Kong in hand and new ports open for commerce, the British influence in the Asian nation increased.

Also, the presence of other foreign powers, notably the French with their eyes on Southeast Asia, and the Americans who looked to Japan as their China.

However, as nationalism grew, both in Britain and China, and with the disdained opium trade still a sticking point, China’s chafing under the foreign Empire’s earlier victory would sooner or later boil over into fresh conflict.

The incident precipitating the Second Opium War took place in Canton. Though not as prominent as during the First Opium War, the port remained an important for trade. On October 8, 1856, the merchant vessel Arrow docked into port.

Though captained by a Britisher and registered under Great Britain, the vessel was in fact manned by a Chinese crew, utilizing legal technicalities to take advantage of the beneficial trade agreements towards Britain.

While the captain dined with a fellow captain aboard another vessel, they witnessed two Imperial junks approach the Arrow. The Chinese proceeded to apprehend the native crew, stating that it contained pirates.

A complex history of varied registrations and owners gave the vessel a shady history, and three of the crew’s vessel were, in fact, known pirates. Despite this, the captain protested loudly, both to the Chinese and British, about the apprehension of a technically British crew and ship.

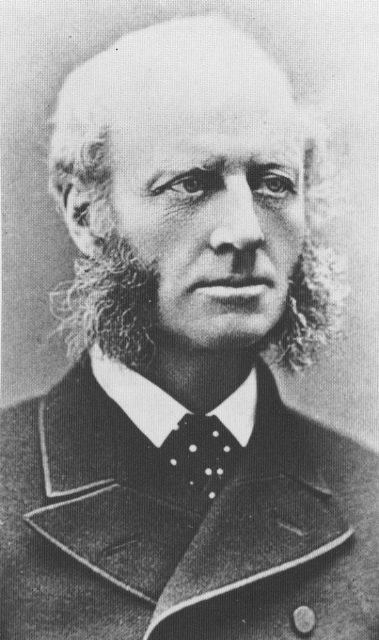

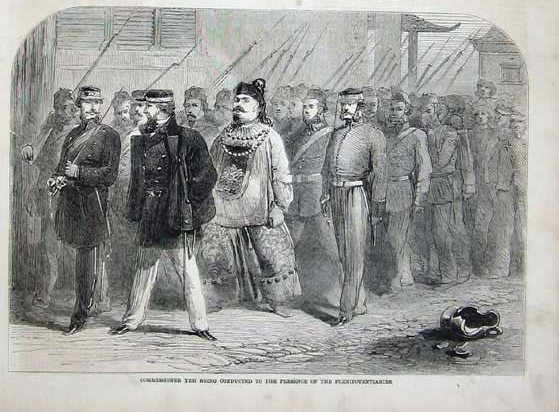

The Acting British Consul, Harry Parkes, went to the Chinese and demanded the return of the prisoners. The Chinese replied that the crew were known witnesses to the locations of pirates, and were thus needed to testify about the accused’s guilt or innocence. Having been given the runaround, Parkes wrote to Ye Mingchen, the Imperial Commissioner in charge of international relations and Viceroy of two provinces.

In a carefully worded, highly flattering letter, Parkes requested the return of the captured crew, with assurances that they would be investigated for any crimes by the British, in conjunction with the Chinese authorities.

The letter sent, Parkes complained, with much less careful wording, to his British superior, the governor of Hong Kong. Parkes argued that, Chinese or not, the Arrow’s crew and the ship were registered under the British flag, and thus granted all the protection to those flying the Union Jack.

To resolve the matter of foreigners entering Canton –a sticking point since the First Opium War- Governor Bowring was willing and ready to send sixteen men-of-war and three steamships to Canton; a show of force unprecedented by the British since the end of the first war.

Two days later, Ye replied to Parke’s letter. He stated he could release all of the crewmembers except the three pirates, and that the vessel, despite its registration, was Chinese built and owned. Thus, neither the vessel, nor its crew, were British or subject to the rights of the Treaty of Nanking that ended the First Opium War.

Outraged, Parkes wrote another letter to the Hong Kong Governor, stating that in retaliation for the crew’s apprehension the British should do the same to one of the responsible junks.

Governor Bowring agreed, and, on October 14, the British gunboat Coramandel bloodlessly apprehended a Chinese junk and towed it to Whampoa. As the vessel was privately owned, it failed to evoke the outrage Parkes hoped it would. Compounding the issue, Bowring investigated the Arrow’s records and discovered that the vessel’s British registry expired September 27.

Ignoring the technicality that the ship was not in fact British at the time of its apprehension, as well as the presence of pirates serving as crew, Bowring continued to work to provoke the Viceroy. On October 21 he had Parkes deliver an ultimatum: He had twenty-four hours to free the entire crew, provide a public apology, and promise to respect all British shipping, regardless of in whose name the ship was registered. If Ye refused, the Royal Navy would force him to their “complete satisfaction.”

Ye, stuck between a rock and a hard place, like other Chinese officials before him, tried to meet the British halfway; he returned the entire crew, refused to apologize, and pledged in the future to consult with the foreigners regarding potential pirate crewmembers.

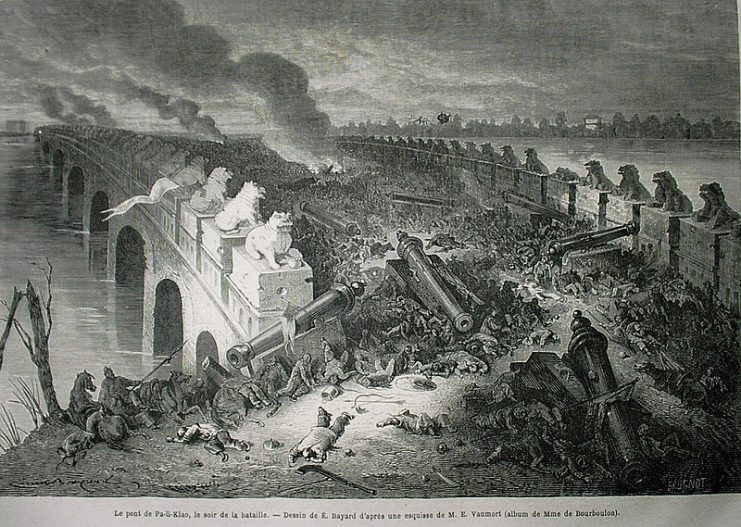

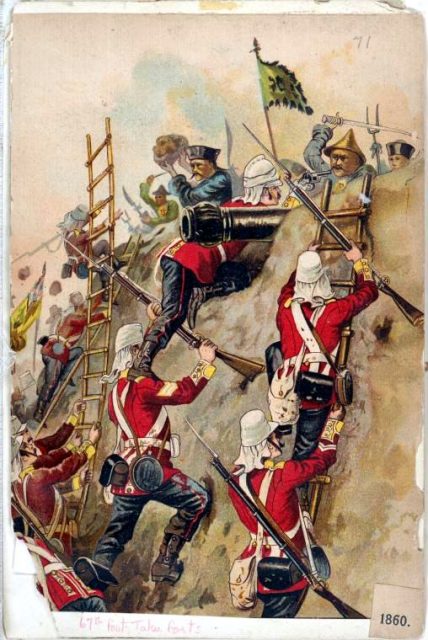

Ye and Parkes wrote back and forth, Ye desperate to save face –and his head- while also well aware what the British were trying to do. Pouncing on the wording of his replies, Parkes ordered, on October 23, for the local Rear-Admiral to seize and destroy the four forts five miles south of Canton.

Two of the Chinese forts returned fire before surrendering, and in the firefight five Chinese died. The first shots and deaths of the Second Opium War had been fired and lost. The local British contingent mobilized for further action, while Ye readied the city militia. Bringing the war home for the Viceroy, the British shelled his residence, though they failed to kill the man.

The war that would follow would further humiliate the Chinese, boost British nationalism and commerce, and open China to other foreign inroads and abuses. Despite their best efforts, the might of the Qing Dynasty was once again powerless against the British Empire.