The Cádiz Expedition of 1625 involved a king’s boyfriend and an invasion of Spain. It had disastrous consequences for Britain and left the Spaniards extremely confused.

Introducing George Villiers – the son of minor aristocrats. He was so hot that Bishop Godfrey Goodman (Queen Anne’s chaplain) described him as “the handsomest-bodied man in all of England.”

Enter King James I of England and Ireland. Everyone knew he liked men. They did not have a problem with that. They did have an issue with his boyfriend, though – Robert Carr, 1st Earl of Somerset.

So they initiated a meeting between Villiers and the King in August 1614 and… voilà! The 48-year-old King broke up with Carr and hooked up with the 21-year-old hunk of burning love.

As the 2nd Baronet, Sir Edward Peyton, put it, “”the King sold his affections to Sir George Villiers, whom he would tumble and kiss as a mistress.”

Unsurprisingly, Villiers rose through the ranks and became the Duke of Buckingham – an extinct title revived just for him. In that position, he began negotiating the King’s foreign affairs. The countdown to the destruction of the English monarchy had begun.

In 1623, Villiers went to Spain. With him was James’ son and heir – Charles I, Prince of Wales. The latter was to wed a Spanish princess to seal the peace with Spain.

Unfortunately, Villiers so annoyed the Spaniards they asked the British government to execute him. Fortunately, Parliament was not amenable – since when did Protestants obey Catholics?

When Villiers returned to Britain, he made up for the mess by declaring war on Spain. That made him popular, but Parliament was not having any of that, either – too expensive.

In 1624, Villiers was again allowed to negotiate Charles’ marriage – this time to Henrietta Maria of France. Fortunately, it went smoothly. Unfortunately, she was a Catholic. Parliament and the public were furious!

Things got worse. James I wanted to take back the Palatinate (a series of German states) for his son-in-law – Frederick V. Elector Palatine. Ernst von Mansfeld, a German mercenary general, was hired but failed. They blamed Villiers for that, too.

By then, James was weak and mostly bed-ridden, so power lay with his son and boyfriend. To protect his beloved, before dying on March 27, 1625, James replaced his entire Parliament with one more amenable to war with Spain.

To save himself, Villiers came up with a brilliant plan. During the Elizabethan Era (1558-1603), Britain had pulled itself out of an economic recession by plundering Spanish ships. Why not do it again?

Spain was rich because it had the Americas. Treasure ships brought back gold and silver – enriching not just Spain, but ensuring Catholic power, as well. Britain would surely recoup whatever it spent on a war with Spain and ensure Protestant dominance!

Parliament approved. Villiers claimed his expedition would be the likes of which had “never went out of England,” and was to be given “victuals as will last a whole year.” He was half right.

Sir John Ogle, a war veteran, was put in charge. Ogle took stock of what the Duke had prepared and wrote that the men were completely unfit “by reason of age, impotency, sickness and other infirmities.”

He could not say as much to the second most powerful man in Britain. Claiming to be sick, Ogle resigned, left London, and retired to his estate.

Villiers then appointed Edward Cecil, 1st Viscount Wimbledon, to the task. Cecil was another war veteran, but no navigator. Still, he could not resist the promotion.

By October 1625, Britain had about 100 ships and 15,000 men – but there was a problem. With so many ships away the country was vulnerable. A deal was made with the Dutch who sent over 15 warships. Some would guard the English Channel, while others would join the raids in exchange for a share of the spoils.

The fleet set off on October 6 only to encounter storms. Though none sank, a number had to sail back to Britain. The rest continued toward Spanish waters only then realizing they did not have enough food and water.

No problem – the Spanish galleons would provide! Except the Spaniards knew about the storms and had avoided them, leaving Cecil with nothing. He turned then to the coastal cities believing the treasure had to reach them first.

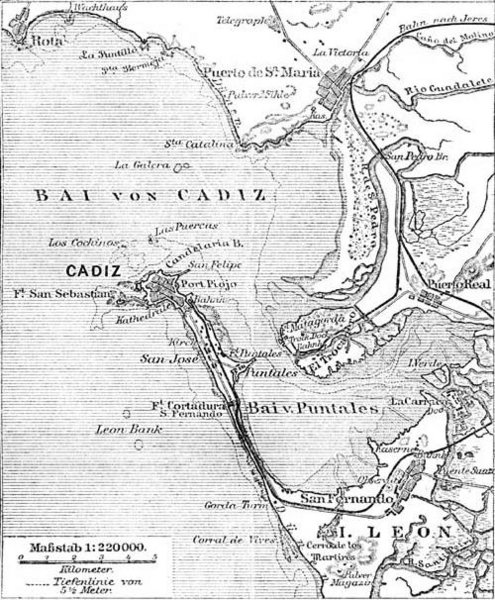

He sailed to Cádiz, but the residents had been through this before. The British had burned the harbor in 1587, but could not breach the city’s defensive walls. They made up for it in 1596 when they occupied Cádiz for a month, looted it, then burned it down.

Cádiz had not only been rebuilt, but it had also improved its defenses, which was why Cecil could not make a repeat of 1596. As to Cádiz’s ships, they had sailed off when they saw him coming.

Desperate, Cecil ordered the capture of Fort Puntel outside the city. It had been part of Cádiz’s old defense network and now lay abandoned.

The Fort was surrounded by equally abandoned houses. The men plundered what they could, but there was not a lot. First rule of a siege? Take food with you.

There was a warehouse filled with barrels of wine – it was too much. Cecil lost control of his men. Those still sober were whipped and bullied back onto the ships. The rest were still drinking or too far gone when the Spanish troops arrived.

The soldiers did not even bother with guns. They used their swords, instead. Over a thousand British died, probably unconscious at the time.

Cecil tried chasing those galleons again, but they were better navigators than him. With no more food, he returned to Britain in shame.

Some survivors were dropped off in Ireland, where they quickly died. At Galway, their emaciated bodies so terrified locals the mayor ordered the town’s gates closed against them. Off Plymouth, they started dumping corpses into the sea.

Villiers’ plan had cost Britain £250,000 and thousands dead with nothing to show for it. He was executed on August 23, 1628.

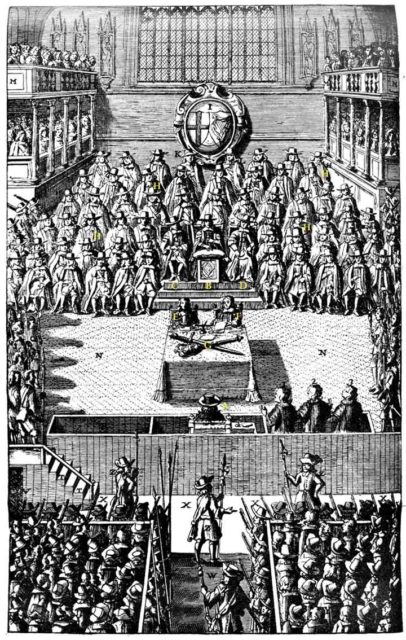

Charles, now King, was disgraced. He had twice dismissed Parliament to save his father’s ex-boyfriend for nothing. The English Civil War broke out in 1642, and Charles was executed for high treason in 1649.

Britain abolished the monarchy and remained a republic until 1660.