As children, we are told to eat carrots to improve our eyesight. Carrots, we are informed, will help us see at night and will be generally beneficial to our eyes.

The question is: where did this idea come from? Is there scientific evidence for this, or was it all just propaganda from the British government?

In terms of science, the evidence is pretty sound regarding the benefits that carrots provide.

They are high in beta-carotene which the body uses to make Vitamin A. This is the vitamin which helps your eyes to convert light into signals that can be transmitted to the brain. More vitamin A means you can see better in low light conditions.

In contrast, Vitamin A deficiency can cause poor vision. When you do not get enough Vitamin A for a prolonged time, your cornea could disappear.

While this is proof that carrots are good for your eyes, do they live up to their “wonder vegetable” reputation?

The truth is that it is hard to eat enough carrots to improve your night vision substantially. Our bodies don’t convert beta-carotene into vitamin A very efficiently, so even eating a lot of carrots wouldn’t be as helpful as, for example, taking a vitamin supplement.

In addition, too much vitamin A can be toxic to humans, so our bodies naturally regulate our levels to avoid this.

Carotenemia could also occur if you eat too many carrots, which is a harmless condition that turns your skin orange or yellow.

The idea that carrots are a wonder vegetable comes from WWII and the British government.

In the 1940s, the Luftwaffe would often wait for the cover of darkness to attack. To make this harder, the British government ordered citywide blackouts. At the same time, the Royal Air Force started to use radar technology.

While ground radar was known, Airborne Interception Radar was new and top secret. This radar gave the RAF the ability to pinpoint German bombers before they got to the English Channel.

In order to keep this technology secret, stories were circulated by the government about why their top fighter pilots were so effective.

One of these fighter pilots was John Cunningham. Nicknamed “Cat’s Eyes,” Cunningham was the first RAF pilot to shoot down a German bomber using the new radar technology. He would go on to make 20 kills, 19 of which were at night.

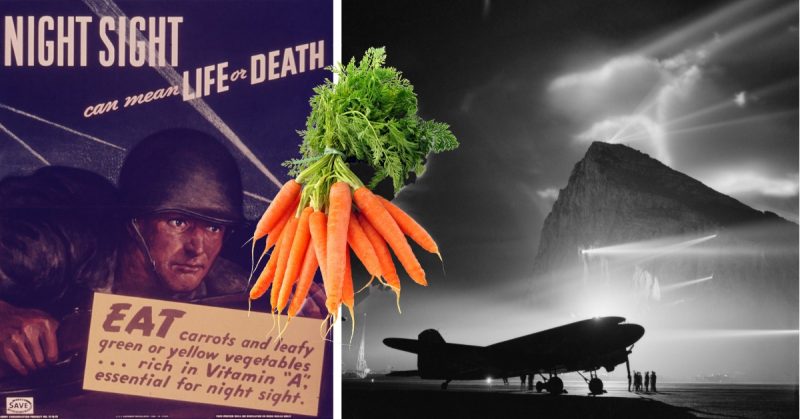

When the newspapers of the time asked how the RAF pilots were shooting down planes in the dark, they were given a rather strange answer. They were told that the pilots were so successful because they ate a lot of carrots.

It is impossible to know if the British government set out to fool the German government with this exaggeration, which is what some people claim.

However, Bryan Legate, the assistant curator of the Royal Air Force Museum in London, does not believe that this was the case. He thinks that the British Air Ministry went along with the carrot theory, but knew that the Germans wouldn’t be fooled by this.

The German government was aware of the British ground radar installations. They would not have been surprised by the placement of radar in RAF fighter planes.

Evidence does suggest that the Germans did not fully believe such propaganda as there is nothing to show that German pilots started eating carrots in an attempt to level the playing field.

However, the general public in Britain was a different story. It seems that they generally believed eating carrots would help them see better during the blackouts ordered by the government.

Advertising stating the benefits of carrots were posted across the United Kingdom. This has led to another theory behind the carrot propaganda.

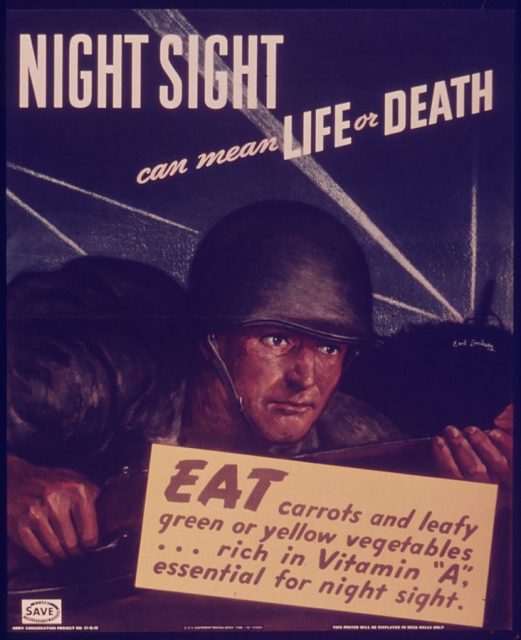

It has been suggested that the British government was pushing carrots and other vegetables on the public during the food supply blockades.

Carrots were not rationed. They could also be grown at home and often formed part of Victory Gardens. The Ministry of Food encouraged the production of carrots to the point where there was 100,000 tons of surplus.

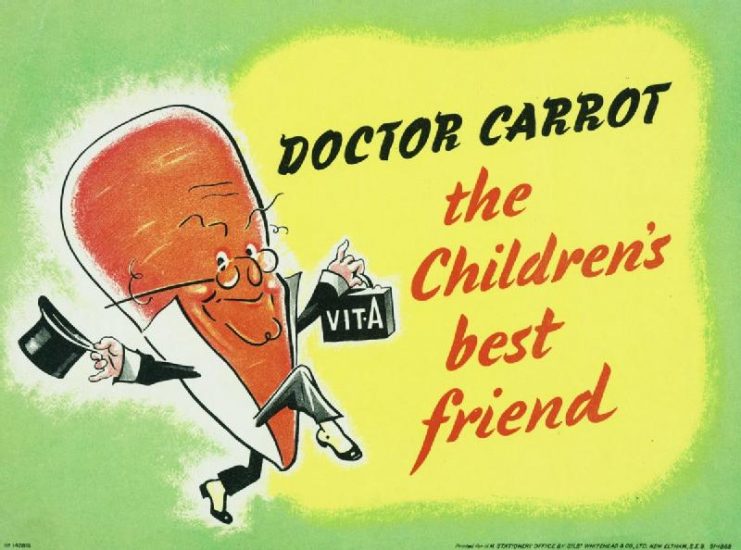

“Doctor Carrot,” the children’s best friend, started to feature more in adverts.

Cooking publications also stated that carrots could be used to sweeten desserts in the absence of sugar which was held up in the blockade.

Most of us have become used to thinking that carrots are a wonder vegetable that can help our eyesight. This is true to a certain extent, but eating a lot of carrots will not give you amazing night vision as many believe.

Instead, this idea came from propaganda during WWII to increase carrot use and production, as well as to serve as a cover for new radar technology.