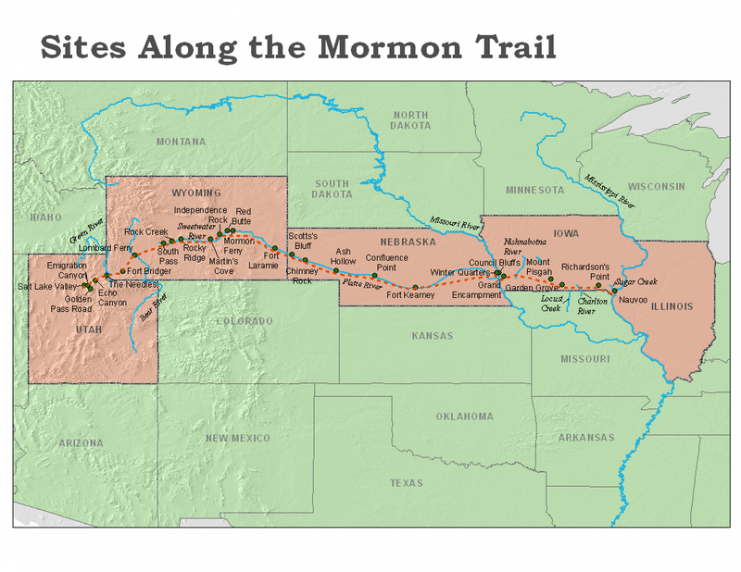

Throughout the nineteenth century the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, more commonly known as Mormons, struggled to find a home for themselves. Eventually, their journey led them to the sands of Utah, which at the time was controlled by the young Mexican republic.

The remote location suited the Mormons, who often faced persecution and violence from their fellow Americans wherever they traveled. Unfortunately, in 1848, the Mormon’s so-called Deseret ceased to be Mexican. Once again, they found themselves in the United States.

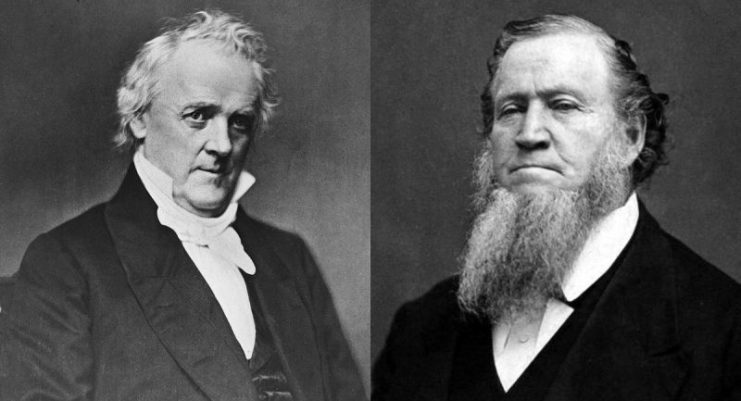

The Mormons hoped they would be left in peace, and that their time of persecution was at an end. For a time it seemed this would be the case, but things changed in 1857. President James Buchanan, fearful of territorial governor Brigham Young’s power, replaced him and several key territorial officials with Gentiles.

Expecting the Mormons to resist the change, President Buchanan sent 2,500 soldiers to ensure a peaceful transition of government. The Mormons, fearing annihilation at the hands of the Utah Expedition, rallied themselves for a possible campaign, readying what weapons they had while hoping to avoid bloodshed at all costs.

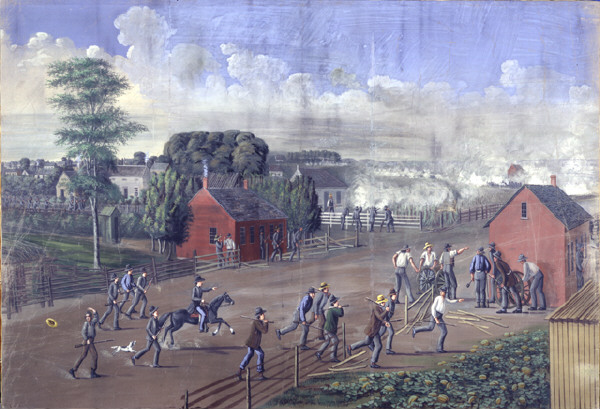

Daniel H. Wells, having led Mormon forces in the defense of Nauvoo, Illinois, advised the leaders of the Utah forces to “annoy them in every possible way. Use every exertion to stampede their animals and set fire to their trains. Burn the whole country before them and on their flanks. Keep them from sleeping, by night surprises; blockade the road by felling trees or destroying the river fords where you can.”

The Mormons prepared for a guerrilla campaign in which they hoped no lives would be lost, lest they exacerbate their tenuous place in the country, one they struggled for years to settle. Their first act was to seal off entry into the Salt Lake Valley, stymieing the Utah Expedition in hopes of wearing them out.

Once the locals started destroying army supplies and stampeding livestock, the situation escalated, and the President called for more troops. Young, meanwhile, asked for more men to take up arms in the local militia.

As 1857 wore on, both sides started working for a peaceful solution to the conflict. The ever indecisive President Buchanan was starting to receive political pressure to settle the situation before it escalated into full-on rebellion. Young, meanwhile, readied his people to travel south and prepared them to burn down their homes if necessary.

At the same time, in August, a friend of the Mormons in Pennsylvania named Thomas Kane started negotiating with the federal government for a resolution that didn’t involve bloodshed or arson.

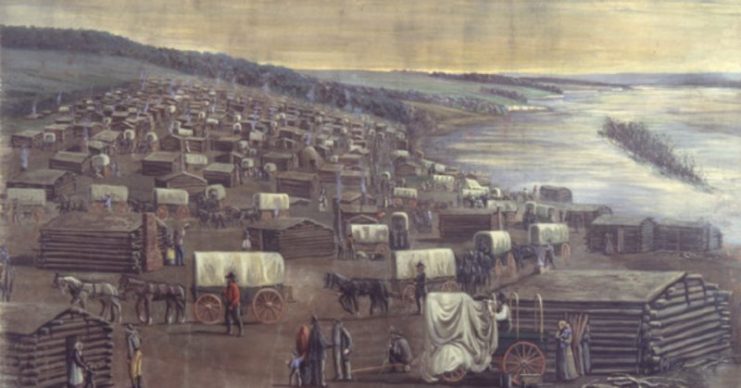

Despite such efforts, peace seemed elusive. Over 30,000 Mormons fled southward, while the militia continued to harass the supply trains and livestock of the federal troops.

Eventually, Kane reached an agreement with the U.S. government, and he and Alfred Cumming, who was designated to replace Young as governor, arrived in Utah without incident. Though Young agreed to turn over the government, tension in the summer of 1858 remained high as more federal troops entered the territory.

Facing increasing congressional pressure, President Buchanan, after talks with the Mormons through a peace commission sent in the summer, formed a resolution to the so-called war. The government was peacefully changed to one with more Gentiles, and in exchange the Mormons were pardoned for the rebellion.

Read another story from us: Between Two Rivers: Opening Shots of the Mexican-American War

American troops, many of them bitter at their inability to properly fight the Mormon militia, marched unimpeded through the streets of Salt Lake City and established a fort at Camp Floyd. From there they would keep an eye on the Mormons until a much larger, more organized, and far deadlier group of rebels forced them out of Utah and onto the field of battle.