No one expected Joseph Coulon de Villiers (1718-1754) to be the cause of a worldwide conflict. A minor French noble, Sieur de Jumonville became an officer in the French army serving in America in 1733 at the age of fifteen, through the patronage of his lieutenant father. The elder Villiers died that same year, and Ensign Jumonville’s career was unremarkable until 1754 when he was assigned to Fort Duquesne (current-day Pittsburgh, PA).

As a minor officer who had not managed to distinguish himself by his mid-thirties, Jumonville could hardly have expected choice assignments, but even so, the task he took on in late May was unappealing. He was to lead a force of 35 men to confront a much larger company of Virginia colonial troops who were encroaching into what the French felt was their territory.

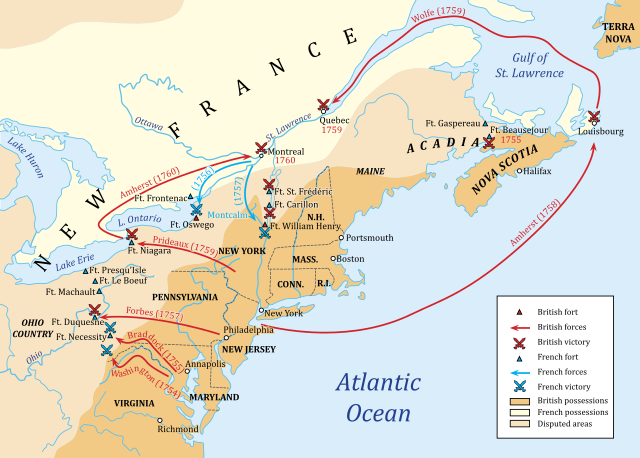

Both the French and British colonial governments claimed the Ohio River Valley as their own, recognizing it as key to westward expansion on the North American continent. Nor was European international competition the only conflict: the British colonies of Virginia, Pennsylvania, and New York all had competing claims, and the Iroquois Confederacy, the Western and Eastern Delawares, the Shawnees, and the Mingos were all in a complicated political dance for control of the region’s native population.

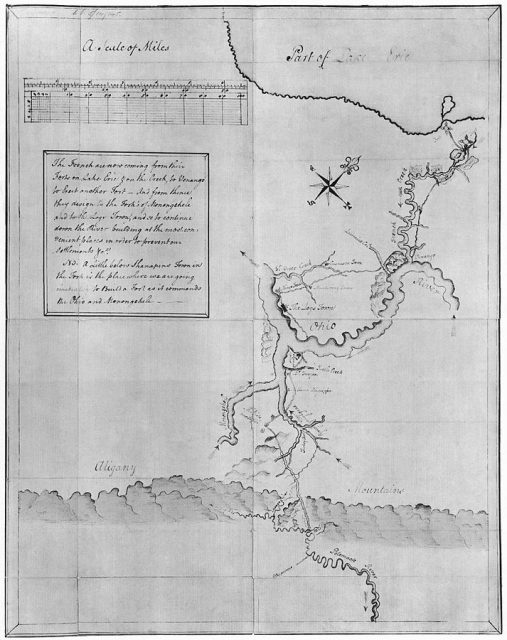

The French had come from their northern strongholds on the Great Lakes and built several forts in the Ohio Valley, which alarmed both the Native populations and the British colonial governments. Virginia raised a company of two hundred militiamen, led by a newly-minted lieutenant colonel named George Washington, who at 22 was about to engage in his first military conflict. It was Washington’s force that Jumonville was sent to intercept.

French records indicate that Jumonville’s mission was simply to meet the Virginia force, inform them that they were encroaching on French territory and ask them to leave the Ohio Valley. Washington himself had performed a similar mission for the British in the previous year and had been rebuffed by the French regional commander, but allowed to return to Virginia in safety. Ensign Jumonville likely expected to get the same reception.

But Washington had split his force twice before encountering Jumonville’s, and they met on terms which were much closer to equal. To face Jumonville’s 35, Washington had only 40, plus twelve Mingo warriors who had directed him to Jumonville’s camp and represented themselves as allies but were not under Washington’s command.

It’s unclear who initiated the action, but within minutes the French and the Virginians had exchanged three volleys of fire, after which the French surrendered and were taken prisoner in what must compete for the title of the least interesting, albeit important, battle of all time.

The battle itself, if it had been all that happened, might not have been important; while British and French troops firing on each other was a big deal politically, this type of skirmish might have been glossed over by the regional commanders or their political superiors. Only one Virginian was killed, and while it’s unclear how many French soldiers died in the fighting the number was also small.

The reason we don’t know how many French soldiers died in the fighting is the same reason the battle became important: Tanaghrisson, the chief of the Mingos. Tanaghrisson had been a diplomatic leader for the Iroquois in the Ohio Country and had strongly supported an alliance with the British.

As French influence in the region grew, Tanaghrisson’s influence waned, to the point where in 1754 he was the leader of only a small, homeless band of Mingos. His only chance at regaining power was a war between the European powers, and he set out to provoke one.

While Washington’s Virginia soldiers were re-organizing themselves, believing the battle was over, Tanaghrisson’s Mingos moved into the French camp and killed the French prisoners. Tanaghrisson himself went for Jumonville. After speaking to the Ensign for a moment, Tanaghrisson put his hatchet through Jumonville’s skull and washed his hands in his brains.

Tanaghrisson’s words to Jumonville: “Thou are not yet dead, my father.” The French had established a paternal metaphor in their relations with American natives, in which the ultimate father was the King of France. Tanaghrisson was expressing that his actions were not merely the killing of prisoners but a symbolic repudiation of French rule. Through Jumonville, he killed Louis XV in effigy.

French authorities could not stand such behavior from a British ally, one supposedly under Washington’s command, and the tension quickly blossomed into war. A conflict which began in the American backcountry would not limit itself to just to the American colonies but spread to Europe, the Caribbean, India, West Africa, Uruguay, and the Philippines. The Seven Years’ War would remake the map and redefine the politics of five continents, all from a disgraced chief’s hands in the brains of an undistinguished minor officer.