Since its inception, in-air refueling has turned out to be an essential aspect of air force practice. Air forces around the world have adopted this technique to save time and improve an airplane’s flight time.

Also known as aerial refueling, mid-air refueling, or tanking, in-air refueling is simply a military practice of refueling an airborne aircraft. It involves transferring aviation fuel from the tanker or donor aircraft to the receiver while both are in the air. The concept is akin to connecting a running vehicle to a mobile tanker truck.

The concept of in-air refueling gained greater significance during the Cold War. The United States required nuclear-armed bombers to remain airborne 24/7. They wanted to deter any Soviet strikes or, in the event of a strike, effect prompt and adequate retaliatory strikes. Furthermore, these heavy bombers needed to be stationed in the air to execute a first strike immediately if ordered to do so.

The first suggestion of in-air refueling came in 1917 from an erstwhile Imperial Russian Navy aviator, Alexander P. de Seversky. He would later become an engineer in the U.S. War Department. He got a patent for his concept of in-air refueling three years later.

Based on his development, the first in-air refueling happened on June 27, 1923, between two biplanes flying 500 feet (152 meters) above Rockwell Field in San Diego, California. This was conducted by four U.S. Army Air Corps officers: Lieutenants John Richter, Virgil Hine, and Frank Seifert, along with Captain Lowell Smith.

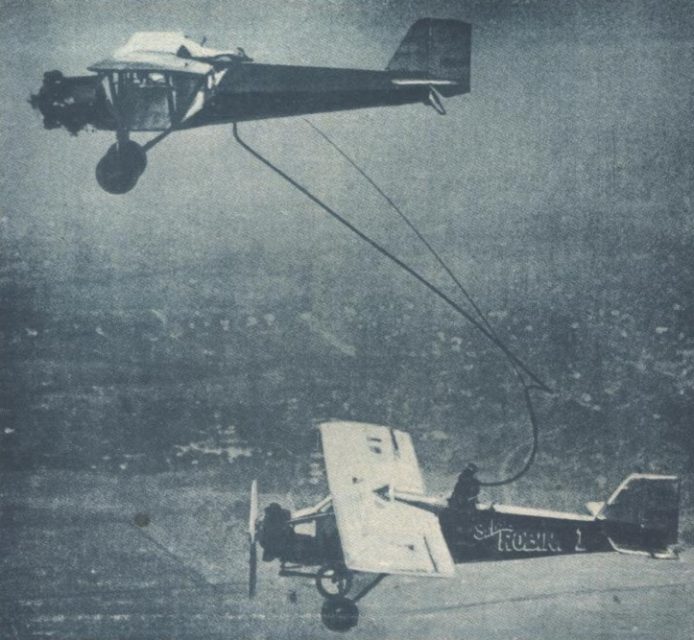

Although this was the first plane-to-plane aerial refueling, it was not strictly the first aerial refueling. The actual first mid-air refueling occurred in 1921 during a rather stunt-like experiment by the trio of Wesley May, Earl Daugherty, and Frank Hawks. Wing walker Wesley May had successfully carried 5 gallons of gasoline on his back from Frank Hawks’ aircraft to Earl Daugherty’s JN-4 airplane. When he climbed over to Daugherty’s plane, he transferred his gasoline into its fuel tank.

Although successful, this method was too risky to be feasible. Not only did it demand wing walking skills, a talent usually reserved for rather intrepid barnstormers, but also the amount of fuel transferred was minimal.

Seversky’s methodology employed a hose which would run from a tanker at a higher altitude down to the receiver plane. This was how the in-air refueling of 1923 occurred. Before then, a number of tests had been carried out on the equipment needed for the process.

One such test occurred in April 1923, when two airplanes remained connected in the air for forty minutes without actually transferring any fuel. This experiment was conducted to test the effectiveness of the hose and the shut-off valve, which was meant to cut off fuel transmission quickly if the connection got broken. This experiment also doubled as a flight endurance test.

On August 27, 1923, a flight endurance of 37 hours was achieved by three DH-4B aircraft. The record was broken in June 1930 by a flight endurance of 553 hours with 223 refueling contacts. This was subsequently broken on July 27 by a Curtiss Robin “St. Louis” aircraft which achieved 647.5 hours of uninterrupted flight.

Despite setting the landmark for in-flight refueling, the hose method was still rather clumsy and dangerous. A more practical process was required.

By 1934, the British Royal Air Force through Richard L.R. Atcherly came up with a more advanced technique called the “crossover system.” This would later be refined into the grappled-line looped-hose technique. This method improved the efficiency of the whole process. Further improvements morphed the looped-hose system into the probe-and-drogue system which has become one of the two main in-air refueling techniques.

In 1948, aerial refueling became a priority to the United States Air Force (USAF). Consequently, the USAF acquired and equipped two B-29 Superfortresses with two sets of looped-hose equipment from Flight Refueling Limited (FRL). In May that year, flight testing was conducted. The success of those tests prompted more equipment to be ordered in June, and all new B-50s alongside subsequent bombers were equipped with fuel receiving equipment.

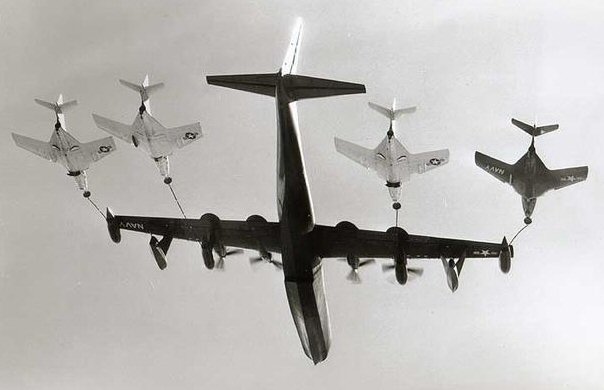

The flying boom system came in the late 1940s through The Boeing Company, following the need for faster refueling. Boom-equipped aircraft of the United States include the KC-135 Stratotanker and KC-10 Extender among others which are very long-range aircraft with enormous fuel capacity.

A U.S. Air Force North American RB-45C Tornado (s/n 48-031) of the 323rd Strategic Reconnaissance Squadron, 91st Strategic Reconnaissance Wing at Barksdale Air Force Base, Louisiana (USA), is being refueled by a 91st Air Refueling Squadron Boeing KB-29P Superfortress

The USAF continued using both probe-and-drogue and flying boom systems for several years but would drop the former owing to the flying boom’s ability to transfer fuel at a much higher rate.

However, the U.S. Navy dispensed with the latter owing to the ease with which the probe-and-drogue could be mounted on smaller aircraft operating from carriers.

In-air refueling was used for the first time in combat during the Korean War.

During rescue missions in Vietnam, a CH-3 Jolly Green Giant helicopter was fitted with refueling equipment for an experimental refueling procedure from a KC-130 aircraft.

The introduction of the KC-10 extender saw the incorporation of both the drogue and the boom systems, enabling aerial refueling of both Navy and Marine aircraft.

In-air refueling has proven to be very useful in extending flight durations. It has also been shown that this procedure can reduce fuel consumption for flights exceeding 3,000 nautical miles. Furthermore, this process substantially improves the maximum takeoff load of airplanes. Aircraft can initially carry less fuel and more payloads since it will be refueled when successfully airborne.

Read another story from us: Tejas MK1 Fighter Completes India’s First In-Air Refueling

Apart from the United States and The United Kingdom, several other countries have adopted the in-air refueling technique. These include France, Russia, Canada, Algeria, Morroco, Iran, China, among others.