“The arrow would be worth a great deal if it could tell men of honor from the rest,” said a Spartan hoplite as his integrity was questioned by an Athenian citizen.

The soldier had become a prisoner of war after the conflicts at Pylos and Sphacteria. His presence and reply were baffling. The courage of Spartan soldiers was renowned throughout the Greek world, a legacy cemented by King Leonidas’s heroic stand at the Battle of Thermopylae in 480 BCE.

But these Spartan prisoners had surrendered in what seemed to be a glaring contradiction of the “death before dishonor” attitude expected from them. What had caused the greatest warriors of their time to lay down their arms?

To answer this, it should first be asked: why was the idea of Spartan heroism so important? And what made this situation different? Even today, Spartans are renowned as an ultimate military machine, the epitome of soldiers and their ethos.

In the war that ravaged Classical Greece in the years from 431 BCE to 404 BCE, the great powers of Athens and Sparta would clash across the Aegean Sea and beyond. The world war of its time, it would shape the course of Western Civilization in the centuries to come.

The war created a power vacuum that would eventually be filled by the Kingdom of Macedon under Phillip II. His son, Alexander, would later conquer the Persian Empire and usher in the Hellenistic Age, a time of colliding cultures in a Greco-dominated world.

At its core, the Peloponnesian War was political.

Following the defeat of the Persian king, Xerxes I, during the Greco-Persian Wars of the 5th century BCE, Athenian ambitions were heading toward an empire, much to the ire of the many independent city-states of the Classical Greek world.

While Athens continued to push the boundaries of this independence, those that felt powerless to preserve their sovereignty turned to Sparta. It was the only state that had the potential to stop the growing threat of Athenian domination.

The final straw would be Athens’s interference in Corinthian colonial politics. Their issues with the growing democratic state were enough to catch the ear of the Spartan kings and members of the assembly.

Fearing the loss of their position as a dominant power in Greece, Sparta capitulated, beginning an extensive and destructive war.

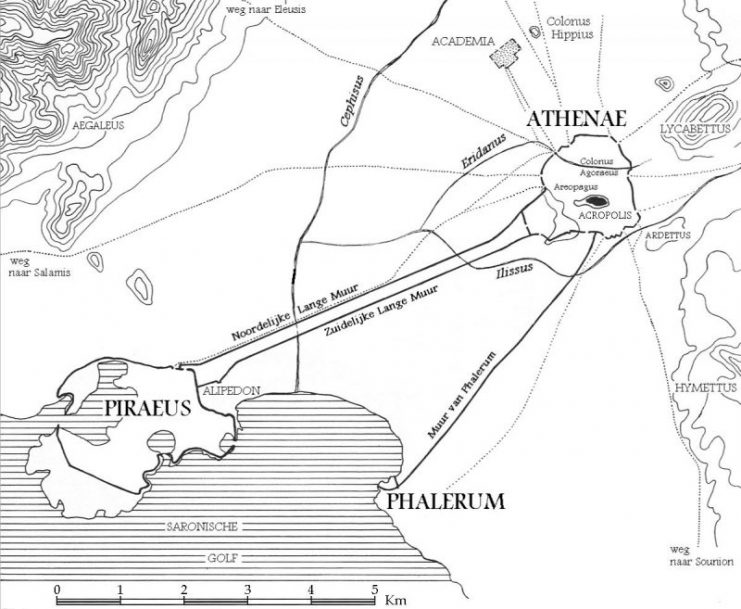

After several years of fighting, little headway was being made by either side. Athens was content to use its powerful navy and remain behind the city walls while Sparta wielded the might of its army on land.

With a force made up of their famous professional soldiers, the Spartans ravaged the Athenian territory of Attica in attempts to bait their opponents out. But the Athenians would not budge.

Neither had any reason to clash on their opponent’s favored ground, and much of the war could be fought in proxy conflicts within the remaining city-states that were struggling to pick a side.

Those that joined Sparta would be known as the Peloponnesian League, while those that were dominated by or allied with Athens formed the Delian League.

The Battle of Pylos in 425 BCE marked a turning point so severe that Sparta would become desperate for peace and a quick end to the war.

Four hundred and twenty Spartans became stranded on an island off the coast of the Peloponnese. They were completely surrounded by the Athenian navy.

More importantly, 120 of these soldiers were from the most elite class of Spartan society: the Spartiates. Their loss would be catastrophic to the unique political and social system of this renowned city-state. Spartan philosophy had created very serious population problems, and they could not afford the death of so many important men.

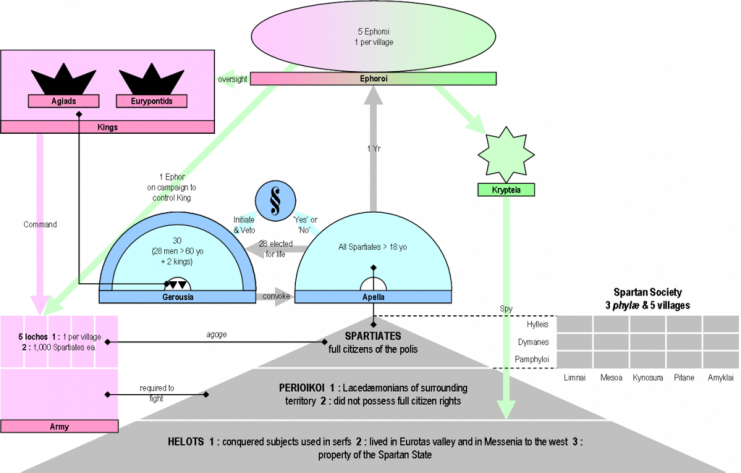

Spartiates were the warrior class, those whose primary purpose was to train for war and wage it when necessary. They were the citizens of Sparta, landholders and members of the assembly, the closest reflection of democracy within their government.

Because the Spartiates focused solely on soldiering and politics, most of Spartan society was made up of non-citizens who performed the economic and material tasks that would support their militarized state.

The focus on preparing for war and the social segregation necessary to support this system made procreation a ritualistic task that needed to be performed but was done so only on occasion. Most of these soldiers were too busy to focus on anything else but war.

Although the Spartiates kept their positions at the top, they constantly struggled to retain their numbers.

Below the Spartiates were the Perioikoi, the working middle class. They were the smiths, artisans, masons, and merchants. Perioikoi did the jobs necessary for a civilization to function at the high level expected of Classical Greek city-states. However, being below the Spartiates, they remained non-citizens of the state.

The helots, slaves tied to the estates of the Spartiates, comprised the lowest and largest class on the Spartan ladder. They were responsible for growing and harvesting the crops needed to feed their military masters.

Most of the helots were Greeks from Messenia, a people who resided in the south of the Peloponnesian peninsula just west of Sparta. They had been conquered by the Spartans and enslaved some time during the Greek Dark Ages, a period beginning in the 12th century BCE with the fall of the Mycenaean Civilization and the rise of Classical Greece in the 9th century BCE.

Since the helots were severely oppressed at the brutal hands of the Spartiates, controlling the slave class was a constant source of frustration for Sparta. Their tendency to rebel and aid Sparta’s enemies was a frequent problem the government needed to address in order to maintain their warrior class’s position at the top of the hierarchy.

Ritualistic culling of the helots was seen as a necessary measure to keep them in line and remind them of their place within the Spartan social structure. It would often be a part of the Spartiates’ rigorous military education, the Agoge, as helots could be killed for any reason and at any time by their masters.

Perioikoi and helots would often accompany the Spartan army as retainers and support, but they were expendable as non-citizens. The possibility of losing 120 of their already small number of Spartiates, however, was enough to cause panic within the Spartan government.

Sparta was known for its caution and reluctance to fight wars abroad, as a lack of soldiers in the Peloponnese provided opportunities for the helots to organize rebellions and wreak havoc across Spartan lands. If the helots were ever successful in breaking their chains, Sparta could collapse entirely.

Because of this, Sparta was often criticized for being too slow to act, being so intrinsically tied to their system of slavery.

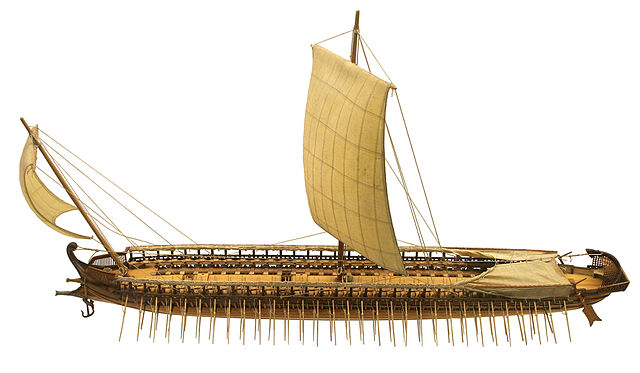

Sparta had amassed a fleet of their own during the war: 60 triremes meant to aid Spartan sympathizers on the island of Corcyra. However, the occupation of Pylos by the Athenian commander Demosthenes concerned Agis, the Spartan king campaigning in Attica.

Realizing that the Athenians planned to stay and make a fortified position of the area to assist rebel helots, he quickly turned his soldiers around to attack the small port-town on the coast of the southern Peloponnese.

As the Spartan army and navy attacked the fortified Athenian positions simultaneously, they were repeatedly repelled until they were forced to abandon their aggressive strategy and settle in for a siege. A day later, an Athenian fleet meant to intercept the Spartan navy at Corcyra arrived to reinforce Demosthenes.

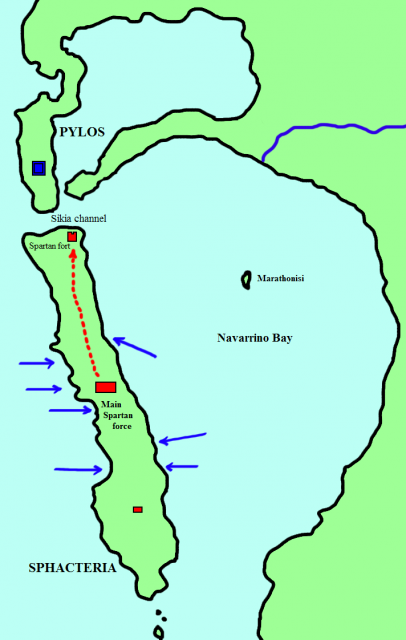

The harbor created by the Greek mainland and the narrow island of Sphacteria made only two entrances possible to what is now called the Bay of Navarino. When the Athenian fleet attacked through both passes at the same time, they overwhelmed and crushed the Spartan ships within.

A contingent of Spartan soldiers had been using the island as a staging ground for their attacks on Pylos, but now they found themselves stranded as the Athenians held complete control of the sea.

In uncharacteristic desperation, Sparta sued for peace. A deal was struck as negotiations began, the Spartans being forced to surrender their remaining triremes as collateral to send food to their beleaguered troops.

As the Spartan ambassadors attempted to convince the Athenian assembly to accept a long term peace agreement, the statesman Cleon managed to form a case to refuse them. Making outrageous demands that would strengthen an already strong Athenian position throughout Greece and the Aegean Sea, the Spartans were compelled to return home empty-handed as the temporary truce at Pylos came to an end.

Athens refused to return the ships they had taken from Sparta during the negotiations. They insisted that, during the armistice, a force of Spartan soldiers had attempted to breach their fortifications.

Sparta could do nothing to stop this. They were already in a losing position and could only hope their hoplites on Sphacteria might repel an Athenian assault.

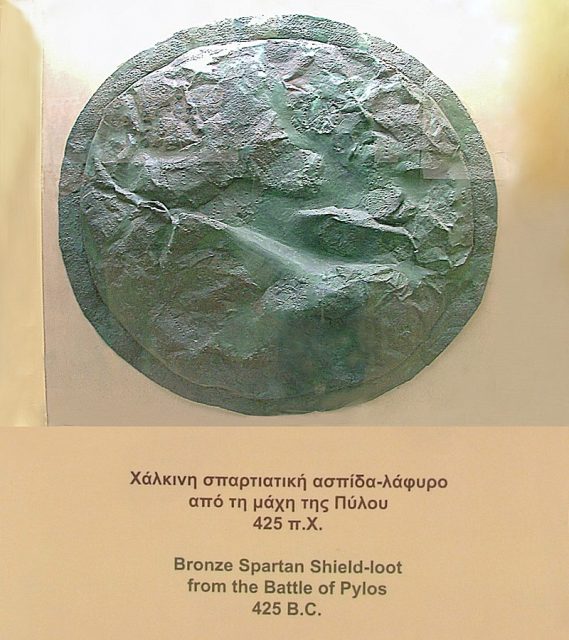

When Athens finally landed soldiers of their own on the island, the subsequent Battle of Sphacteria would see these famous warriors defeated. After being pushed back by the Athenians to an ancient fort on the northern end of the island, those that were left standing sought a way to stop the bloodshed.

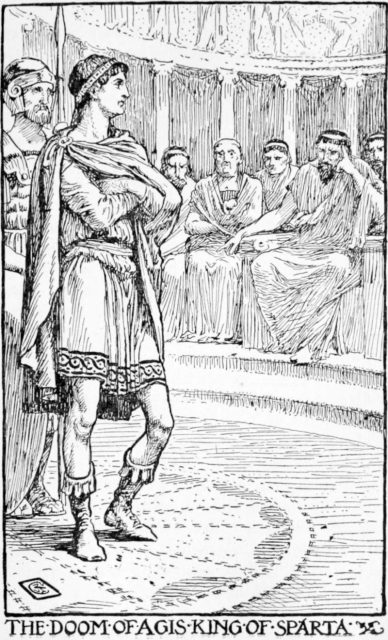

Looking to avoid responsibility for the disaster, the Spartan government sent a herald to deliver a message to their defeated soldiers: “The Lacedaemonians bid you to decide for yourselves so long as you do nothing dishonorable.”

Hearing this, the Spartans laid down their arms and chose to become prisoners of the Athenians.

These prisoners would be used as leverage to prevent the Spartans from invading the lands of Attica again, their death being guaranteed if any attempt was made. The Spartans could never afford to lose so many of their elite soldier-citizens

This stalemate highlighted some harsh realities of the Spartan system: it was fragile, stagnant, and always prone to failure because of its own strict design.

While the Spartan military legacy lives on, its failures and problems have not. The portrayal of their prowess in battle belies the precarious political and social structure that supported them.

Though the Peloponnesian War would end in victory for Sparta after the surrender of Athens in 404 BCE, it would mostly be due to a series of catastrophic military mistakes by an over-confident and arrogant Athenian military.

Read another story from us: Spartans – Men Who Were Born To Fight

After becoming the hegemonic power of Classical Greece, the Spartan system would be unable to maintain control over the other city-states. The problems they constantly faced regarding population, governance, and social structure would eventually lead to their defeat by the Thebans at the battle of Leuctra in 371BCE.

This defeat paved the way for Macedonian conquest and the world-shaking adventures of Alexander the Great. Though the Macedonians would allow Sparta to retain its independence, this legendary city would never return to being the beacon of power it once was.