The War of 1812 was a defining moment in American and Canadian history. On land and sea the United States fought against the British colossus, avoiding defeat more through stubborn luck than anything else. The war birthed the American Navy, gave the Canadians their identity as a future commonwealth, and launched and collapsed political careers.

It also settled the boundaries of the Old Northwest, the lands that would form the future states of Wisconsin, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and Michigan.

Michigan especially found itself a prominent theatre of the war. At the edges of the American frontier, its lands bordering native tribal lands and British colonies whose actual borders remained in doubt, the future state found itself caught between the interests of all three parties throughout the war.

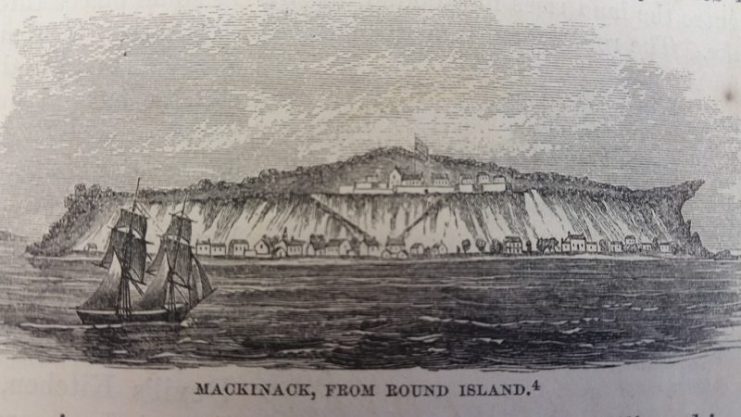

At one of the many meeting points of the lands in those early years of American history lay a small island named Michilimackinac. From here, fur traders from all points gathered to trade their wares.

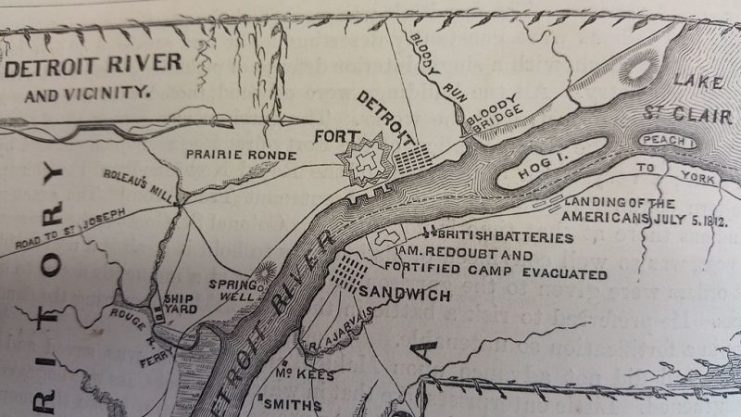

Those close ties also made the area a campaign theatre during the War of 1812. The British maintained few strategic assets in the Great Lakes region, as the bulk of Canada’s population centered around Montreal and Quebec. In order to protect their trade interests further west, the British went on the offensive in the Old Northwest.

Detroit was considered by the British the lynchpin of the region’s American strategic points, and they sought to capture it as part of a possible acquisition of the territories south of the Great Lakes.

While the British military planned their campaign, the Canadian fur traders also plotted. To them, the small island of Michilimackinac, an important fur trading hub in the region, matched Detroit’s strategic importance.

The various Canadian fur companies rallied their own militias as war seemed ever closer. As a nexus for both the local fur trade and the most northern military outpost of the United States, capturing the island was also a key campaign goal for the British.

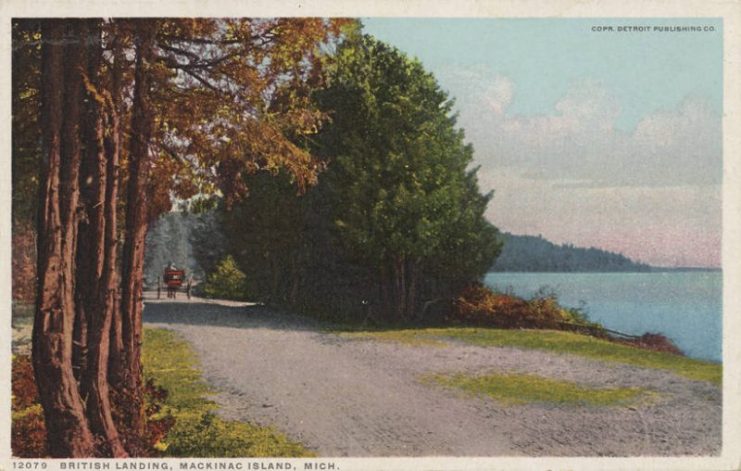

Barely had the war started before the British and Canadian fur traders moved to secure the island fortress at Michilimackinac. Amassing several hundred allied natives, local militia, and fur traders, Captain Charles Roberts led a flotilla of canoes toward the fort. Under the cover of darkness, the attack force snuck onto the island, landing unopposed on July 16, 1812, at roughly three in the morning.

Forty four British soldiers, 100 voyageurs, three hundred natives, and two pieces of artillery prepared to fight fifty-nine American soldiers who had no idea the British were coming, no idea they were a target, and no idea war had even been declared. With the artillery pieces placed on high ground overlooking the fort, the American garrison commander, Lieutenant Porter Hanks, surrendered without firing a shot.

In a simple move and without bloodshed, the British forces had secured the northern Great Lakes, opening the way to march south and capture Detroit. Outnumbered and outgunned, the furthest reaches of the American frontier faced a combination of native allies, British regulars, and local militia. With the fall of Michilimackinac, the only thing protecting the future state of Michigan was the fort at Detroit.

Read another story from us: Port Miami, Ohio – Lost in the War of 1812, Found, and Lost Again

Though a minor incident in comparison to the war as a whole, the taking of the island was seen by the Canadian fur traders as a critical step in their conquest of the northern fur trade. For them, the island’s capture and fall of Detroit would, potentially, once again secure their dominance of the fur trade.