The Mystic Massacre was an armed invasion of a Pequot village at Mystic, Connecticut in New England that took place on May 26, 1637, during the Pequot War of 1636. The relentless struggle among the Native tribes for sovereign control of the European fur trade led to a series of murders and raids that finally culminated in the Pequot War, pitting the dominant Pequot tribe against its close relatives (now turned enemies), the Mohegan and Narragansett tribes, which were allied with English colonists.

Prior to the arrival of the Dutch in 1611, the Pequot and Mohegan tribes existed together as a united entity. However, that changed after the discovery of an abundance of beautiful Native American shelled beads and beaver fur in the territory. The subsequent cultivation of the fur trade made it the biggest and most lucrative business in the region, and heralded the dawn of a period of animosity and rivalry between the tribes.

The Pequot tribe, quickly realizing that wealth equalled superiority over other tribes, did everything in their power to subjugate them.

In realizing their ambitions, they used forceful means in some situations to extend their superiority, sometimes engaging in warfare. They struck a deal with the Dutch to control the trade, but were far from being loved by the other tribes, who felt resentful about the Pequot domination and would stop at nothing short of eradicating their oppressors.

Opportunity came to these tribes with the arrival of the English colonists to Connecticut in the 1630’s. The Mohegan tribe and other tribes with similar interests, aware of the difficulties between the colonists and the Pequot tribe, promptly allied themselves with the colonists to fight a common enemy, thus creating the Pequot War.

Famous among the battles fought during the war was the massacre at Mystic. Mohegan warriors sailed aboard three water vessels, along Massachusetts Bay, under the leadership of their sachem, Uncas.

Colonial militia were led by Captain John Mason and Captain John Underhill, and Mason went to the Narragansett territory to request their support in the scheme to overthrow Pequot leadership. They arrived there on 18 May and engaged in negotiations with the grand sachem, Chief Canonicus, and his eight lower ranking sachems.

Negotiations were concluded after two days and on 23 May, 200 Narragansetts armed to the teeth with war clubs, spears, arrows and axes departed from their settlement, accompanied by 80 English men and 60 Mohegans.

It was a two-day march that left the Englishmen, who were not used to the hot weather conditions in that region, tired and out of sorts. They stopped and made camp that evening near Porter’s Rocks, where they reviewed their plans once more in preparation for the coming battle.

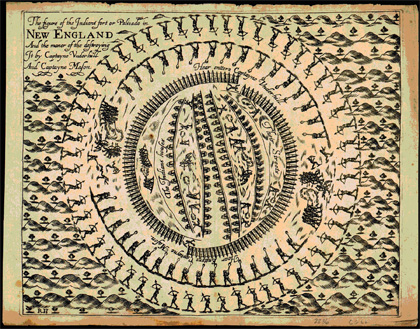

The Pequot Mystic Fort was a circular, brick-built fortification with two entrances, lodged on top of the Pequot Hill very close to the Mystic River. By dawn, the colonists and their Native American counterparts were divided into two units. Each unit was to charge upon the two entrances to the village simultaneously and kill its warriors, saving whatever remained for plunder.

Things didn’t go as planned, however; the whole battle plan was hinged on stealth and surprise, but Mason’s men charging in through the Northeast entrance alerted Mystic’s defenses, and the battle almost became a fair one.

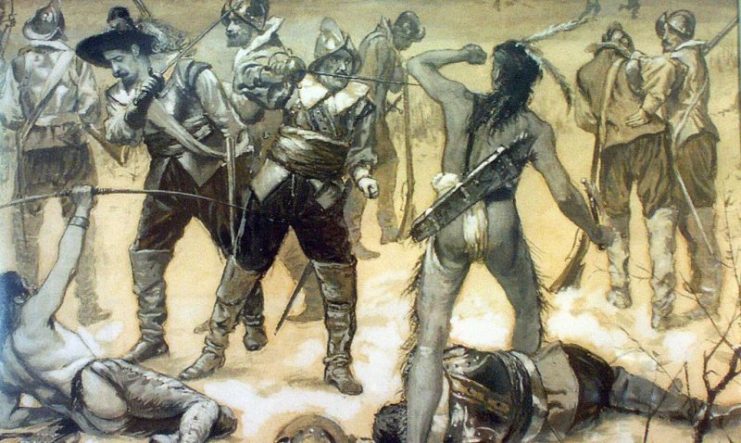

The Pequot warriors, disorganized and only just awakened, quickly gathered what they could and rushed over to challenge the invaders; a fierce battle ensued at the narrow entrance. Mason’s charge eventually yielded fruit, but not without some complications.

Two of his men lost their lives and twenty of them were wounded in the struggle. Filled with rage by the loss of his countrymen and a battle plan went wrong, Mason decided that they deserved no less than to be burned, and with one swift turn, he brought out a firebrand and set the village on fire.

Mason had no intention of letting the unarmed escape or entreat a surrender. The English thus formed a circle around the settlement, blocking off all exits while positioning their lines far enough away to spare themselves of the flames. Through the thick smoke from burning houses, the army shot at any who tried to escape.

Meanwhile the Mohegans and Narragansetts formed an outer circle to strike a final blow to anyone who breached the English line. Observing the brutality of the English, some of the Native Americans could not help but feel sympathy toward the unarmed mothers and children who were also under fire from English guns or even burnt in their sleep.

Within an hour of the invasion, 400 members of the Pequot tribe had been massacred–including the women and children. Later, the English reported seven of them captured while another five had successfully escaped.

Read another story from us: The Creek Indian War in Early America: 8 Important Leaders

The brutality with which the invasion was conducted totally disgusted the Narragansetts, who subsequently returned to their settlement. Their sachems, however, did not refuse the gift of captives which the English brought home to them; the Pequot prisoners were divided among the sachems of the Narragansett and Mohegan tribes.