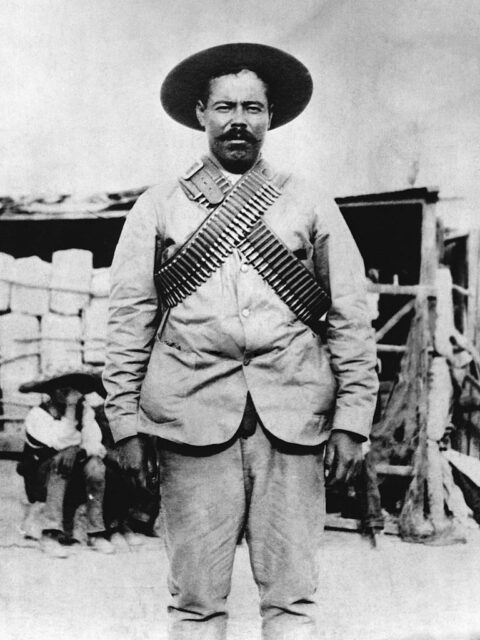

Pancho Villa was easily one of the most beloved leaders of the Mexican Revolution. Born into a humble sharecropping family, he rose from poverty to become a fearless military leader and a symbol of resistance against oppression. His legendary exploits on the battlefield – including against thousands of American troops – and his relentless pursuit of social justice turned him into a folk hero and a national icon in Mexico.

Pancho Villa’s early life

Francisco “Pancho” Villa was born José Doroteo Arango Arámbula on June 5, 1878, in San Juan del Rio, Mexico. His young life was nothing remarkable. He occasionally attended local schools, but spent most of his time working as a sharecropper with his family. He did more and more of this after his father died, along with various jobs as a bricklayer, railway foreman, butcher and muleskinner.

When he was 16 years old, Arámbula decided to make his own way in the world and moved to Chihuahua. By many accounts, this didn’t last long. He was informed that a hacienda owner named Agustín López Negrete had assaulted his sister, so he returned to his hometown to exact revenge.

Supposedly, he killed the man, stole his horse and began life on the run as a bandit by the name of “Arango.” He was arrested for theft in 1898 and, again, in 1902. Although he should have been executed, his close ties with powerful individuals spared his life. Instead, Arámbula was forced to serve in the Federal Army. This “career” didn’t last long, however, as he killed one of his officers, stole his horse and deserted his position.

Becoming Pancho Villa

Yet again wanted by the law, José Doroteo Arango Arámbula assumed the name that would go down in history: Francisco “Pancho” Villa. He continued life as a bandit for a number of years, before he was convinced to join the cause of Francisco Madero, who was working to depose President Porfirio Díaz from power.

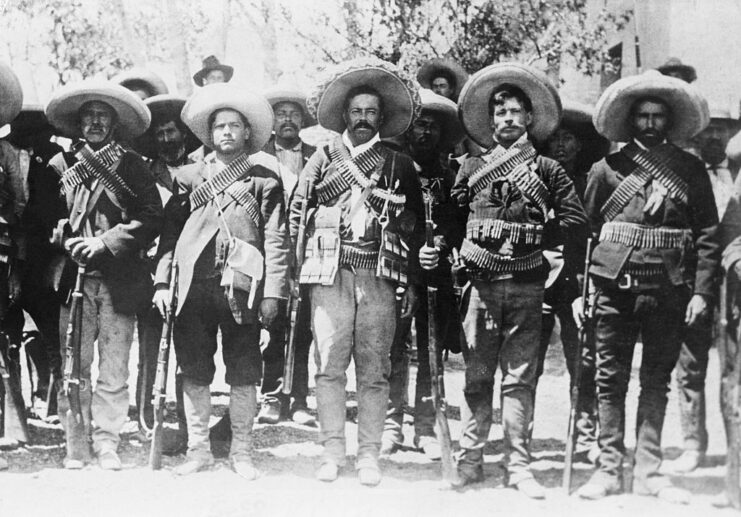

Thus began the Mexican Revolution, with Villa operating as a bandit leader for Madero’s uprising.

Villa proved himself a formidable and charismatic commander, and it didn’t take long for he and his men to capture a train of Federal Army soldiers, the city of San Andrés and a hacienda. He engaged in battles at Naica, Camargo, Pilar de Conchos and Tecolote, winning the first three.

On orders from Madero, Villa was assigned to “deal with” certain members of the Mexican Liberal Party. After accomplishing this, he was made a colonel of the revolutionary force.

Another coup d’etat

In 1911, Francisco Madero was named president, but a resolution to Mexico’s unrest was still far away. More revolutionaries arose under Pascual Orozco, and Pancho Villa agreed to continue fighting for the new president.

Madero was soon assassinated, supposedly by his own military commander, Gen. Victoriano Huerta, who took control of the government. Villa, who’d had a contentious relationship with the military man, decided to fight against him. He served in the Constitutionalist Army of Mexico, under the command of Venustiano Carranza, despite initially disagree with Madero’s decision to name the man as Mexico’s Minister of War.

Villa, however, proved to be too big of a threat to Carranza, given his battlefield prowess saw him appointed as the provisional governor of Chihuahua in 1913. He was ordered to lead an attack on the town of Zacatecas, in an effort to move him away from Mexico City, so Carranza could establish himself as the new Mexican leader.

Concerned he was going to make himself a dictator, Villa and Gen. Emiliano Zapata turned their forces on Carranza, instead.

Guerrilla leader

In the subsequent years, the pair’s forces continued to clash with those under Venustiano Carranza, led by expert tactician Álvaro Obregón. By 1915, following many engagements, Pancho Villa had a significantly diminished force of about 200. Around the same time, the United States decided to declare its support for Carranza as the leader of Mexico.

Despite having few men, Villa retaliated by attacking the American town of Columbus, New Mexico on March 9, 1916. This, along with an earlier killing of 17 Americans in Santa Isabel, prompted US President Woodrow Wilson to send an expedition over the border to capture Villa, under the leadership of Gen. John J. Pershing.

Although they searched endlessly for him, the Americans were never able to locate Villa, as his knowledge of the terrain was far superior. He also received assistance from locals, who revered him. He was known to care deeply for the poor and often provided them with supplies and food when he was able.

Villa evaded US capture for nearly 11 months, when the Americans withdrew from Mexico. While Pershing claimed the expedition had been a success, Wilson said the opposite to the public.

Pancho Villa’s death and legacy

Until 1920, Pancho Villa continued some small-scale attacks. It wasn’t until Venustiano Carranza was assassinated on May 21, 1920 that things changed for the guerrilla leader. Adolfo de la Huerta was named Mexico’s interim president, and the pair negotiated a peace deal. In return for calling off his forces, Villa was granted a 25,000-acre property just outside of Chihuahua. He moved there with his wife, María Luz Corral de Villa, and his remaining fighters.

Although he had 50 personal bodyguards, the former revolutionary was assassinated on July 20, 1923. It’s generally believed he was killed on the orders of Álvaro Obregón, who’d since been elected president.

More from us: Charles Brown Never Received His MoH Because He Deserted Before It Was Presented

Rumor says Villa was interested in entering politics. With an election coming up in 1924, Obregón wanted to ensure there’d be no rivalry to his rule. Nonetheless, Villa’s legacy remains deeply ingrained in Mexican history and culture.