The Hussars were a type of light cavalry that originated in medieval Hungary and were adopted by other European countries. Their bravery, cunning, and daredevil tactics made them legendary, but in 1795, they surpassed themselves.

No such feat has happened before, nor has it been repeated since. One night, these horse riders captured an entire Dutch fleet out at sea. Not only that, but they did so without firing a single shot.

It all started during the French Revolution in the late 1700s. France rejected its monarchy and embraced a republican government.

This made all the other European kingdoms nervous and with good reason. Afraid that such republican ideas might spread beyond France, and even more afraid of literally losing their heads, they fought back.

Great Britain, Spain, Portugal, and the Dutch Republic, among others, made an alliance to invade France and end its fledgling republic. Thus began the War of the First Coalition from 1792 till 1797.

The French had no intention of giving in, of course. So they fought back and repelled the invaders. That done, they went on the offensive.

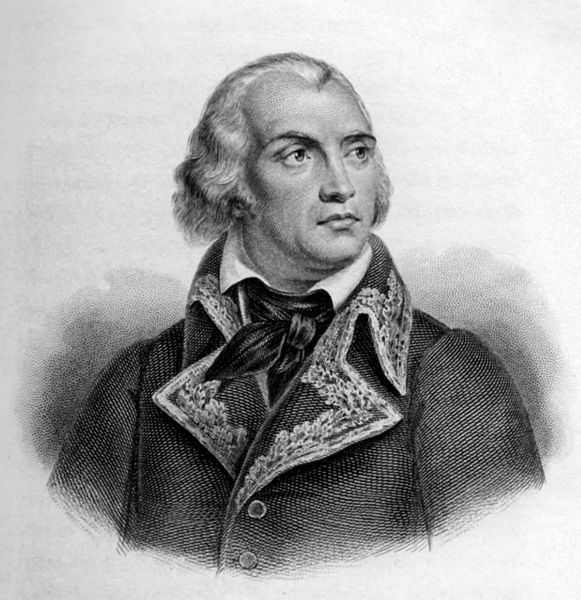

Moving north, French General Jean-Charles Pichegru attacked the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands in late December 1795. His timing was perfect, as the country was deeply divided.

On the one hand were those who supported the stadtholders – not kings exactly, but a type of hereditary head of state. Those who supported them were called Orangists, not because they loved the fruit, but because they favored William V of Orange-Nassau.

On the other were the Patriots who embraced republican ideals and who would have loved to see William ousted. These looked to France and didn’t see Pichegru as an invader so much as a liberator.

There was a third group known as the Regents – a commercial oligarchy made up of merchant families. Political struggles between these three groups ensured that the French met with little resistance.

The capital at Amsterdam was a Patriot hotbed, so on January 18th, 1795 they held a velvet revolution which ousted Stadtholder William. He fled to Britain and the country he left behind became the Batavian Republic.

Two days after Amsterdam’s revolution, Pichegeru arrived and was welcomed by the Patriots. Fortunately, the French showed remarkable restraint and didn’t plunder what was then one of the richest cities in Europe.

But that didn’t mean that the rest of the country was under the control of the French. The Netherlands is made up of many islands, so the French had their work cut out for them.

The Dutch province of Zeeland was still Orangist territory, while the nearby island of Den Helder was part of the Batavian Republic. The British navy had their eyes set on the port of Den Helder, but the weather was against them.

The winter of 1794 to 1795 was particularly harsh, causing many waterways to freeze over. This was bad for the Dutch navy. Being Orangist, they hoped to join William in Britain and add their fleet to his cause. Unfortunately, they had set out too late. As a result, they got stuck in the Marsdiep (the deep tide-race) between Texel and Den Helder.

So there they were – 15 warships armed with a total of 850 guns (more than what Pichegru had). Manned by some 5,000 sailors and marines, this made up the bulk of what was left of the Dutch Republic’s navy. With them was a contingent of about 20 merchant ships – also stuck in the ice.

Den Helder and Texel are on the Zuiderzee (Southern Sea) Bay. Today, it’s closed off, forming the Wadden Sea. But back then, it opened up to the North Sea.

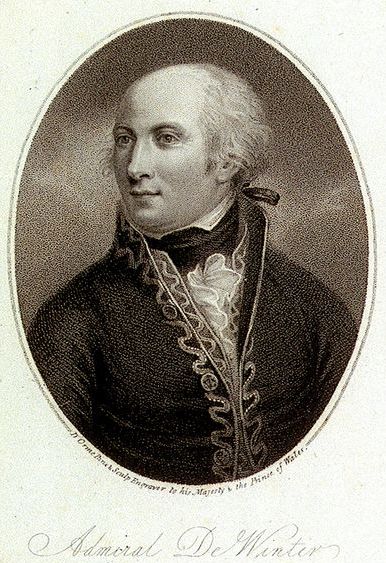

The residents of Den Helder port told the French about the fleet, so Pichegeru ordered his men to check the story out. Dutch Admiral Jan Willem de Winter ordered French Captain Louis Joseph Lahure to the area and see if there was any truth to it.

Lahure arrived on the evening of January 23rd, 1795 with the 8th Hussar Regiment and the 15th Line Infantry Regiment of the French Revolutionary Army (about 2,000 men). According to residents, such a winter was rare, but because the bay was so shallow, the ice should be solid enough to support the weight of an entire cavalry regiment.

The next morning, the men spread out and arranged themselves in several lines to distribute their weight. The tactic also increased their chances of survival – in the event one line broke through the ice, the others would have a chance to get away.

That done, they slowly approached the fleet. While the bulk of the cavalry positioned themselves in the dunes overlooking the harbor, Lahure ordered some of his men to gallop toward the lead ship – the Admiraal Piet Heyn captained by Hermanus Reintjes.

Legend has it that the Hussars snuck aboard the ship the night before and caught the entire crew sleeping. That is a complete and utter myth. Johannes Cornelis de Jonge’s “History of Dutch Maritime Matters” cites the logbooks and diary entries of both sides during that event, so the reality was a lot less dramatic.

The Orangists who made up the crew and the Regents who owned the merchant ships knew that they were on the losing side. As early as January 21st, Reyntjes had received orders from the Council of State of Holland and Westfriesland not to resist the French unless they were belligerent. Nor was he to attack them.

He didn’t have much choice. Only 11 of his ships were manned, while the other four were still undergoing repairs. Nevertheless, there was Dutch pride. As the cavalry approached, Reyntjes ordered his men to their stations in case the French were not in the mood to parlay.

Fortunately, they were. Lahure made it clear that he didn’t want a bloodbath. Reyntjes concurred and the two sides remained where they were. Five days later, de Winter finally arrived and extracted an oath from Reyntjes and his men.

On January 29th, the Dutch Republic’s navy swore to: (1) obey the French, (2) not to sail their ships without French permission, and (3) to maintain discipline.

With that, the French conquest of the Netherlands was complete.