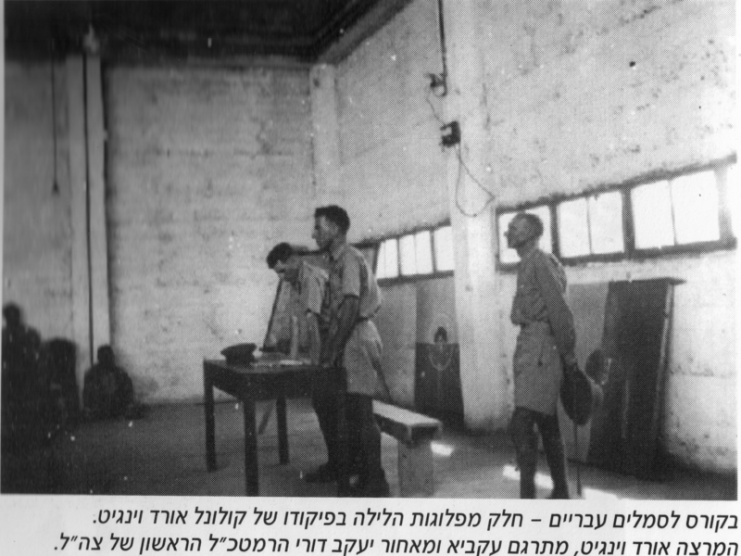

The British armed forces in WWII were famous for a number of reasons: innovation, unreal stubbornness in defense, and much else. They were also known for something else: a large number of truly unusual officers…

Two such men were “Mad Jack” Churchill, who once went into battle armed with a long bow and Blair “Paddy” Mayne, who ripped out the control panel of an enemy aircraft with his bare hands after he’d run out of explosives to do it with.

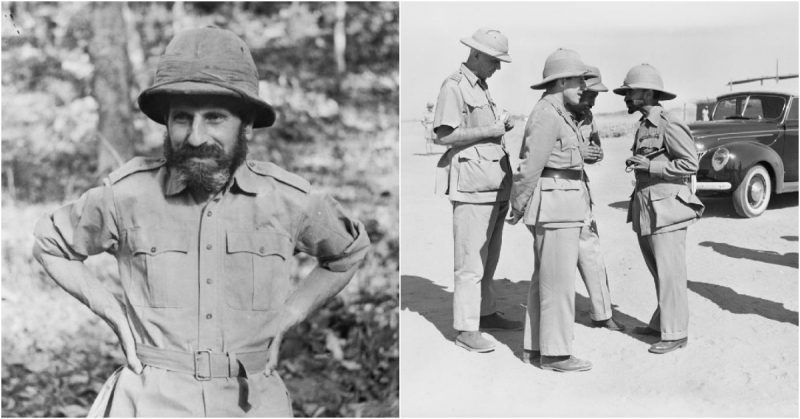

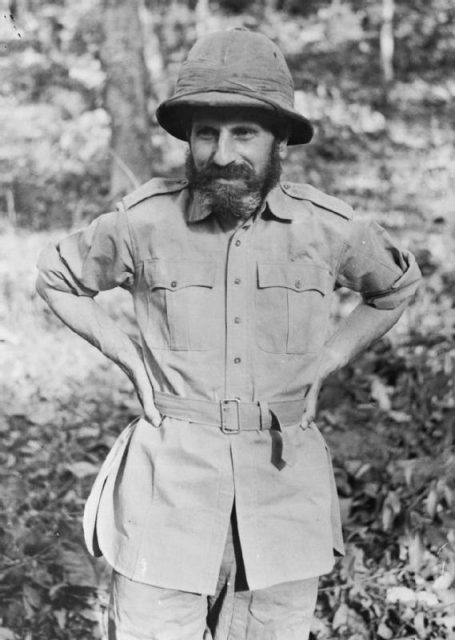

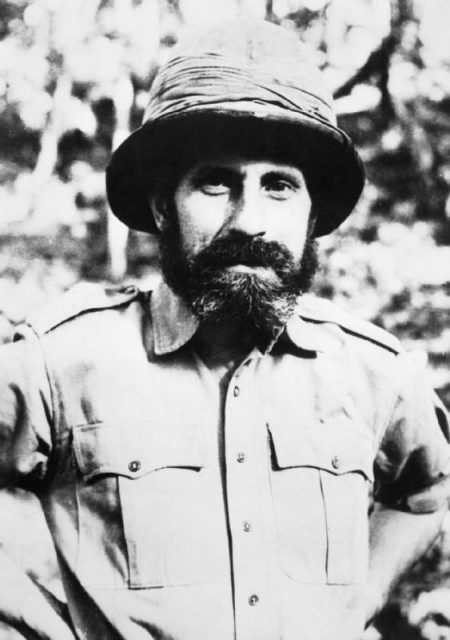

Another unconventional British Army officer was Charles Orde Wingate (always referred to as “Orde”). Wingate, who ate raw onions for their health benefits and who cleaned himself with a hairbrush of sorts, also believed, quite openly, in his own superiority. This, along with his sometimes disheveled looks and bad body odor, alienated more than a few of his commanders and colleagues. He would also occasionally greet visitors to his tent completely naked.

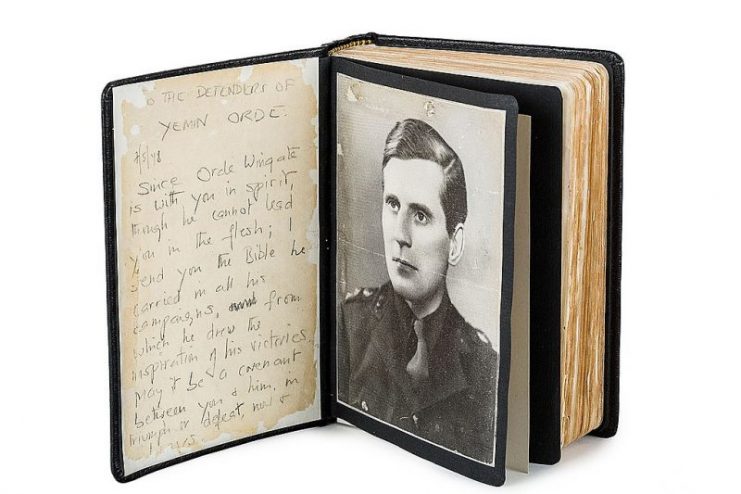

Wingate’s father was a retired officer and member of the Plymouth Brethren, a conservative Christian group, which among other things, emphasized the Bible as the root of all truth. Much of Wingate’s childhood was spent with his siblings learning the Bible.

As a result of a somewhat isolated childhood, Wingate developed into a loner who seemed to alienate people wherever he went. His father championed at giving his children difficult problems to solve and encouraged them to “think out of the box”.

This, and the study of men such as Lawrence of Arabia, whose unorthodox tactics kept the Ottoman Empire on the run in the desert, fostered Wingate’s later ideas about irregular warfare.

In 1921, Wingate was accepted to the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich, which trained artillery officers. Almost from his first day, Wingate developed a reputation. Undergoing hazing for a small infraction, he challenged the senior boys one by one to hit him with the knotted towels each had in his had, daring them to. None did. Such was the force of his personality.

Throughout his early career, Wingate always tested people. Most often it was because he rubbed people up the wrong way and didn’t conform to the “old boys network” that the officer class of the British Army consisted of in those days. In 1928, he was sent to Sudan to both keep an eye on possible uprisings against British colonial rule and to map the territory.

Most officers would’ve considered this posting as a black mark on their career, but Wingate thrived in the Sudan and the harsh environment, considering it a challenge, and a way to “toughen up”.

He was married in 1935, and soon after, was posted to the British Mandate in Palestine (today’s Israel). There, he was decidedly pro-Jewish in a majority Arab country and in an army where many of the officers did not like the natives, either Arab or Jew. Many believe that his conservative religious upbringing caused him to believe in the creation of a state of Israel.

Almost from the start, Wingate pushed the boundaries of his duties, and some say he exceeded them, helping militant Jewish groups with money, arms and intelligence. Wingate, with the reluctant support of General Archibald Wavell, aided militant Jewish groups in attacks against Arab militants during the Arab uprisings of the late 1930s.

Finally, however, Wingate made a public speech in which he called for the establishment of a Jewish state, which caused his dismissal. However, the speech and his leadership gained him the everlasting gratitude of the future Israelis, especially the famed general Moshe Dayan. Today, a square in Jerusalem, a national forest, a youth village and many streets in Israel are named after him.

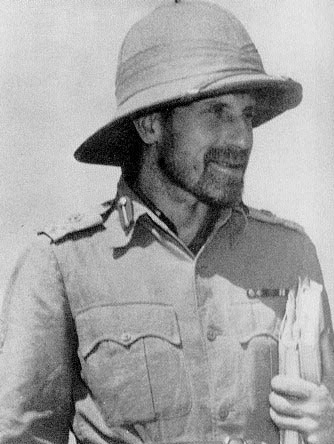

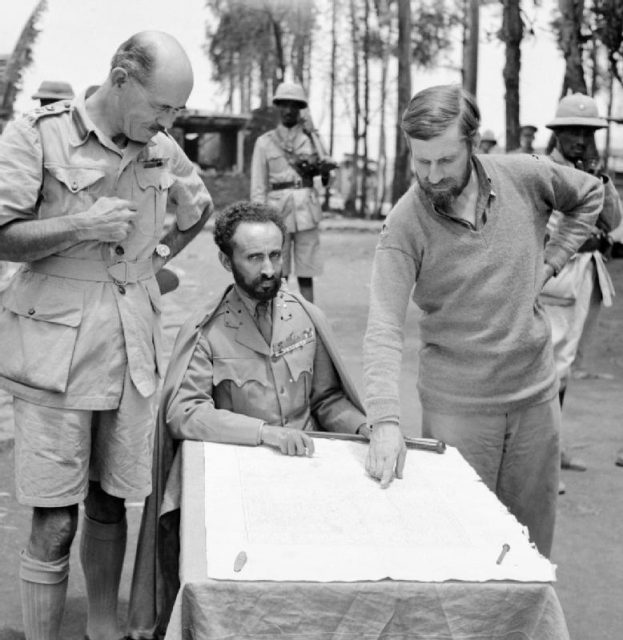

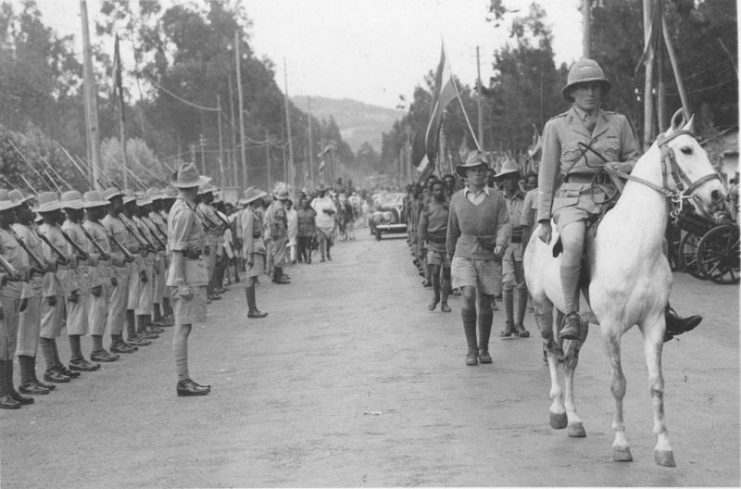

Back in England for the outbreak of WWII, he was soon posted to Ethiopia to organize a guerrilla force around the Ethiopian emperor, Haile Selassie, whose country had been conquered by the Italians in 1936-37. This force, known as the “Gideon Force” was made up of officers who shared Wingate’s vision for irregular troops and who had fought with him in Palestine.

Wingate, like many “different” officers throughout history, inspired either complete disdain or complete loyalty, and many of those loyal to him followed him to Ethiopia and beyond.

Gideon Force, made up of British, Ethiopian and Sudanese soldiers, soon ran the Italians ragged, and in a war that they were ill-equipped to fight, forced the Italian forces of 20,000 men to surrender to their 2,000 in 1941. Emperor Haile Selassie was another of the men who looked upon Wingate with affection and favor.

At the end of the Ethiopian Campaign, Wingate contracted malaria. Unfortunately, he was given too much Atabrine, the treatment of the time, and developed a strong reaction to it. One of the side-effects of too much atabrine was suicidal ideation, and Wingate entered a deep depression in which he stabbed himself in the neck.

A nearby officer saved him, but the incident only added to his reputation of being “eccentric”. Luckily, at the same time, his report on Ethiopia reached Winston Churchill, who was always looking for new and innovative ways to take the war to the enemy. Through Churchill’s connections, Wingate secured a posting to the Burma-India theater.

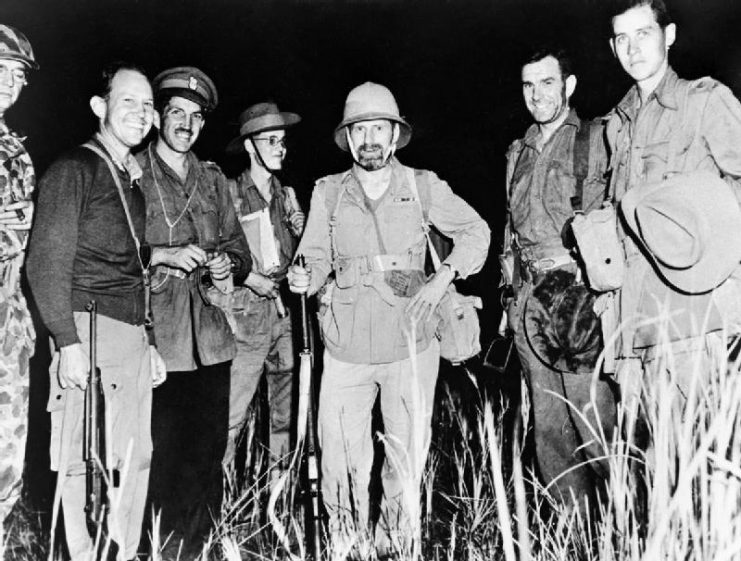

In India, Wingate once again found himself under the command of General Wavell, who ordered him to form a group of guerrilla-style fighters to take the battle behind Japanese lines to disrupt communications, gain intelligence and force the Japanese to divert troops that might be needed in more strategic areas. So, Wingate formed the “Chindits”, whose name is a corruption of the Burmese word for a mythical lion.

The first few months of the Chindits was disastrous, with many men falling sick and Wingate encouraging them to get well through force of will. Many of the men, Indian conscripts, deserted. The force was then made up of mainly volunteers .

The first Chindit mission in early February 1943 was only a partial success. The force made a nuisance of themselves behind Japanese lines in Burma, but poor logistics and an underestimation of how mobile the Japanese were forced the Chindits back to India in March.

They launched another mission shortly thereafter and remained deep behind Japanese lines for the first half of 1943. The Japanese tried to corner the small force, using three infantry divisions to chase a force of perhaps 8,000 men (the force increased in size to about 12,000 in 1944).

In 1944, the Chindits penetrated deep into Burma and per Wingate’s ideas, created strong-points deep in the jungle from which to sortie out and harass the Japanese. This tactic was so successful that the Japanese determined to end the threat from the India border region once and for all.

This resulted in the famous battles of Imphal and Kohima, some of the most brutal fighting to take place in the theater during the war. Along the way, the Chindits harassed and weakened the Japanese column, weakening them for the decisive battles.

In March 1944, Wingate, then an acting major-general, was flying to Chindit bases for inspection when his plane crashed in the Indian jungle. Wingate and nine others lost their lives.

Their remains were unidentifiable and interred in India. Later, after the families wishes, they were interred in the National Cemetery at Arlington, in the United States. The Chindits went on under other commanders until the end of the war, using tactics developed by Wingate, who is still considered one of the innovators of special forces tactics in the 20th century.